|

|

|

Big

problems, big science, better health

The stress of battle

40 life-changing minutes

Progesterone and traumatic brain injury

New synergy in cancer

|

Tracking

brain tumor treatment

Noteworth

Built

from scratch

High marks from NIH

A

new formula for matching kidneys |

|

|

E-mail

to a Friend

E-mail

to a Friend  Printer friendly

Printer friendly |

|

|

|

|

|

Big

problems, big science, better health

The numbers are sobering. A third of the world's 40 million

people with HIV/AIDS are also infected with TB. Of those, 90%

die within months of contracting TB if they are not treated properly.

Finding effective treatments is growing more difficult as various

strains of TB are becoming more widespread and more virulent,

especially in sub-Saharan Africa and India.

Researchers at Emory and in India

are determined to find a solution. Emory's Global Health

Institute, the Emory Vaccine Center, and the International Center

for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (ICGEB) have created

the Center for Global Vaccines, based at the ICGEB in New Delhi.

"Our initial studies will

focus on the basic aspects of HIV/TB co-infection," says

Rafi Ahmed, director of the Emory Vaccine Center. "In fact,

the World Health Organization has just classified HIV/TB as a

unique disease."

India now has the largest number

of HIV-infected people in the world, and 5.7 million of them have

HIV/TB. Although a vaccine exists to prevent TB, it can be used

only in limited circumstances. Thus, Emory and the ICGEB will

focus on developing a therapeutic vaccine that can be used more

widely—one that can be given to people already infected

with HIV/TB. "We want to tackle very big problems, and this

is a very big problem," says Ahmed. "This is very

big science."

"Big" also describes the

new Global Health Institute, a multidisciplinary umbrella for

Emory faculty, students, and alumni who want to solve the world's

critical health problems. Led by Jeffrey Koplan, vice president

for academic health affairs and former CDC director, the institute builds on Emory's history of

global partnerships in medicine, public health, and other disciplines.

former CDC director, the institute builds on Emory's history of

global partnerships in medicine, public health, and other disciplines.

The institute represents a major

commitment by the university. Its $110 million budget includes

$55 million from the university and $55 million from sources in

and outside of Emory.

Among the institute's new programs

is the Republic of South

Africa Drug Discovery Training Program to provide young African

scientists with experience in translating research into health

care solutions. Emory chemist Dennis Liotta, co-inventor of several

successful anti-HIV/AIDS drugs, leads the program. Reynaldo Martorell,

public health professor, directs the Partners in Global

Health Program, an expanded collaboration with the National Institute

of Public Health in Mexico.

Other global health projects will

focus on public health research and training in developing nations,

health care workforce shortages, international bioethics, and

the health impact of global migration.

A separate program affiliated with the institute is the International

Association of National Public Health Institutes, an alliance

of CDC-like agencies dedicated to optimizing global health by

improving public health infrastructure around the world. Koplan

serves as association president.

Learn

more about the Global Health Institute. |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

The

stress of battle

|

|

| |

Despite

ongoing media coverage, it's still hard to fathom

the mental toll of the Iraq war on U.S. veterans. In a study

funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Emory researchers

are testing a new method for treating post-traumatic stress

disorder that may help soldiers deal with troubling memories before depression, memory loss, drug abuse, and other health

problems occur.

before depression, memory loss, drug abuse, and other health

problems occur.

The treatment, mindful based

stress reduction (MBSR), is an eight-week program that teaches

participants how to "intentionally pay attention to

present-moment experiences" such as physical sensations

or perceptions without evaluating those experiences. During

each session, participants are introduced to techniques

such as yoga and meditation. MBSR uses "teachers"

and "students" instead of "patients"

and "therapists."

"We know that medications

sometimes have unpleasant side effects or don't work

at all," says lead investigator J. Douglas Bremner,

director of mental health research at the Atlanta VA Medical

Center. "MBSR is an intervention that not only teaches

a soldier how to cope with painful memories from battle,

but can also be beneficial as a coping skill for life in

general." |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

40

life-changing minutes

|

|

| |

The

40 minutes the doctor spent with Amy changed her life. It

appeared to be a simple case: She needed the stitches in

her arm removed. But only when Sheryl Heron questioned her

about why she put her hand through a window did the truth

come out. Amy was a victim of intimate partner violence.

Heron gave her information

on resources to help her should she decide to leave her

abuser—often the time when abuse is especially violent—and

then Amy was on her way. Only a yea r

later did Heron know the extent of her influence. Amy emailed

her that she had left the relationship, moved to Florida,

and re-enrolled in college. r

later did Heron know the extent of her influence. Amy emailed

her that she had left the relationship, moved to Florida,

and re-enrolled in college.

Gone are the days of patch

‘em up, move ‘em out. Emergency room doctors

and residents now know if they look beyond the injury or

complaint and find domestic violence, addressing the root

cause will help prevent future visits and thus ease the

caseload in the ER. "If you take the time on the front

end to manage what is bringing them in on the back end,

they don't come back," says Heron. "In

the end, you have to consider we are talking about human

beings and their lives."

However, most medical schools

don't have dedicated curricula on domestic violence,

be it children, intimate partner, or elderly. As the new

assistant dean for medical education and student affairs

at Grady Hospital, Heron decided a family violence workshop

was in order for M3 students. The daylong workshop last

fall featured a number of experts in and outside of Emory,

including a staff member of the Grady Rape Crisis Center;

former juvenile court judge Robin Nash, now director of

the Barton Child Law and Policy Clinic in Emory's

School of Law; and a survivor of sexual abuse. All provided

insight on their experiences.

"Medicine teaches us

to fix things," says Heron. "Laceration? Suture

it. Infection? Give an antibiotic. Domestic violence doesn't

have a magic pill, a magic solution. I try to teach physicians

it takes six or seven times for a woman to tell about violence.

We need to consider how we impact people's lives."

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

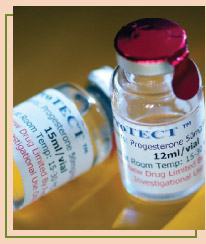

Progesterone

and traumatic brain injury

Progesterone

may be key to reducing death and disability in patients with traumatic

brain injury (TBI). It also appears to be safe. Emory researchers

based these findings on the first clinical study of its type in

the world.

Prior to this study, progesterone

treatment for TBI was studied in laboratory animals for as long

as 15 years. The researchers conducting the clinical trial based

their work on the foundation laid by Emory neurobiologist Donald

Stein, who discovered the neuroprotective effects of progesterone

in the laboratory.

Patients enrolled in the double-blind

study at Grady Hospital had to reach the hospital within 11 hours

of injury. Patients in the study had a blunt traumatic injury,

typically caused by a car accident, motorcycle crash, or fall. Enrolled patients had an

initial Glasgow coma scale (GCS) score ranging from 4 to 12. A

score of 4 to 8 signals severe TBI, usually accompanied by coma,

while a score of 8 to 12 signals moderate TBI. Four out of every

five patients enrolled received intravenous progesterone, and

one of every five patients received a placebo. Thirty days after

injury, researchers used objective rating scales to assess each

patient's neurologic function and level of disability.

accident, motorcycle crash, or fall. Enrolled patients had an

initial Glasgow coma scale (GCS) score ranging from 4 to 12. A

score of 4 to 8 signals severe TBI, usually accompanied by coma,

while a score of 8 to 12 signals moderate TBI. Four out of every

five patients enrolled received intravenous progesterone, and

one of every five patients received a placebo. Thirty days after

injury, researchers used objective rating scales to assess each

patient's neurologic function and level of disability.

"We found encouraging evidence

that progesterone is safe in the setting of TBI, with no evidence

of side effects or serious harmful events," says David Wright,

the emergency medicine physician who led the study. "In

addition, we found a 50% reduction in the rate of death in the

progesterone-treated group. Furthermore, we found a significant

improvement in the functional outcome and level of disability

among patients with moderate brain injury."

Wright's team found no major

differences in the rate of adverse effects among patients who

received progesterone compared with those who received placebo.

About 30% of patients given placebo died within 30 days of injury,

compared with only 13% of those given progesterone. Most patients

who died had severe TBI. Because more severe TBI patients in the

progesterone group survived, it was not surprising that they had

a higher average level of disability at 30 days than survivors

in the placebo group.

Progesterone is a promising treatment

for TBI because it is inexpensive, widely available, and has a

long track record of safe use in humans to treat other diseases.

Wright's team is planning a large, multicenter Phase III

trial to test the effectiveness of progesterone in 1,000 patients

with TBI. In the future, they plan to study the effects of progesterone

treatment in animal models of blast-related injury, a major cause

of death among combat personnel. They also hope to study the use

of progesterone to treat children with brain injuries.

View

a video about the progesterone study |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

New

synergy in cancer

|

|

| |

Brian

Leyland-Jones is the new associate vice president and director

of the Winship Cancer Institute. Leyland-Jones, who specializes

in breast cancer, is known internationally for developing

individualized therapies and novel clinical trials. He comes

to Emory from McGill University in Montreal, where he served

as the Minda de Gunzberg Chair in oncology, professor of

medicine, and director of McGill's Comprehensive Cancer

Center. Brian

Leyland-Jones is the new associate vice president and director

of the Winship Cancer Institute. Leyland-Jones, who specializes

in breast cancer, is known internationally for developing

individualized therapies and novel clinical trials. He comes

to Emory from McGill University in Montreal, where he served

as the Minda de Gunzberg Chair in oncology, professor of

medicine, and director of McGill's Comprehensive Cancer

Center.

At McGill, he led the development

of a clinical trials operation that integrated research

with five clinical trial cooperative groups and more than

40 pharmaceutical companies. His research interests include

pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacogenetics

in clinical trials; translation of preclinical models into

the clinic; biomarker endpoints in Phase I/II clinical trials;

and screening and mechanistic studies of novel targeted

and chemotherapeutic anti-cancer agents. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Tracking

brain tumor treatment

|

|

|

| |

A

newly identified novel biomarker potentially could help

physicians better determine when a brain tumor spreads or

recurs after treatment, reports Winship Cancer Institute

researcher Erwin Van Meir.

The biomarker, a protein known

as "soluble attractin," is normally absent in

the central nervous system (CNS) and undetectable in cerebral

spinal fluid (CSF) unless malignant astrocytomas—the

most common form of intracranial tumors—are present

in the CNS. The CSF can be sampled for analysis of proteins

secreted by CNS tumors.

This newfound ability to identify

biomarkers for malignant astrocytomas means that physicians

will have a minimally invasive method to track the success

of treatments. These biomarkers, singly or in combination,

will provide a fingerprint of the disease and in the future

better define the disease, predict what type of treatment

to use, and allow doctors to monitor how well the tumor

responds to treatment.

"Using proteomic analysis

of the CNS of patients with brain tumors, we have identified

for the first time that attractin levels are elevated in

patients with high-grade astrocytoma," says Van Meir,

who led the study in collaboration with the Dana Farber

Cancer Institute. "Because few noninvasive methods

are available for monitoring CNS malignancies, there is

an urgent need to find reliable indicators." |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Noteworthy

Michael

Johns,

who has led the Woodruff Health Sciences Center for 11 years,

will become chancellor of Emory this fall. In addition to advising

the president and the board of trustees, Johns will represent

the university on health care policy and building partnerships,

such as Emory's research collaboration with Georgia Tech.

For the first time, two

Emory health administrators hold top leadership positions with

the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). Michael Johns,

CEO of the Woodruff Health Sciences Center, is immediate past

chair of the Council of Teaching Hospitals and Health Systems.

Thomas Lawley, dean of the School of Medicine, chairs the AAMC's

Council of Deans.

Physicians with Emory Healthcare provided $70.7

million in charity care in 2005–2006, a 7% increase over

the previous year. At publicly funded Grady Hospital, Emory provided

$24.7 million in uncompensated care, up $2.7 million from the

previous year. About 85% of the physicians at Grady are Emory

medical faculty. |

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

| |

Built

from scratch

|

|

| |

Emory

University Hospital opened a neuro critical care unit that

centralizes most critical medical services for patients

suffering from severe neurologic trauma—including

severe brain injury, strokes, and aneurysms. Just as important,

the unit's design incorporates the importance of family

in the patient's healing.

One of the largest in the

United States and one of only a few of its type in the Southeast,

the unit is staffed by

neurointensivists, critical care nurses, nurse practitioners,

and pharmacists. All played a role in creating the unit,

along with social workers, former patients, and family members.

social workers, former patients, and family members.

"Plans for the neuro

ICU incorporate core principles of evidence-based, patient-centered

design—a holistic approach that focuses on the patient's

physical environment as a tool for healing," says

Owen Samuels (shown left), director of neuroscience critical

care. The unit's design takes into account factors

such as the effects of natural light, noise reduction, and

increasing staff efficiencies.

Also key is sufficient space

to perform intricate procedures at the bedside and thus

reduce transporting fragile patients across the hospital.

A high-resolution CT machine is housed in the unit, allowing

patients to be scanned upon admission and during their stay.

"This unit," says Emory Healthcare president

and CEO John Fox, "has raised the proverbial ‘bar'

and set the standard, locally and nationally, for critical

care."

Learn

more the neuro icu. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

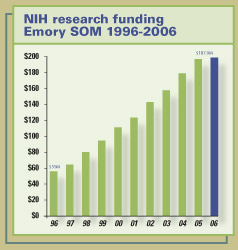

High

marks from NIH

|

|

| |

The School of Medicine now ranks 18th among all U.S. medical

schools in total research grants awarded by NIH for 2006.

The school has climbed steadily in research funding, having

ranked 31st in 1996.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

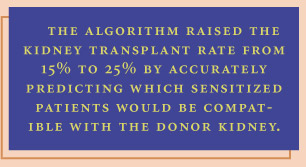

A

new formula for matching kidneys

Many patients on the national waiting list for kidney transplants

have only a small chance of receiving a new organ, no matter

how long they wait. Because of previous transplants, pregnancies,

or blood transfusions, these patients have developed antibodies

that make it difficult to match them with donor organs.

Emory researchers have developed the

Emory Algorithm, a decision process that may give new hope to

these highly sensitized patients. The algorithm may even change

the way kidneys from deceased donors are allocated in the United States.

deceased donors are allocated in the United States.

Sensitized patients have developed

antibodies against human leukocyte antigens (HLAs), which play

an important role in the body's immune response to foreign

tissue. While these patients represent one-third of the national

waiting list for kidney transplant patients (and 50% in Georgia),

they receive about 15% of deceased-donor kidney transplants

each year.

The United Network for Organ Sharing

coordinates the nation's transplant system through a point

system primarily based on wait time, sensitization, and HLA

matching. When a "perfect match" occurs, the kidney

is offered to the person at the top of the national list. If there are no perfect matches, the kidney becomes

available to transplant centers in the region from which it

came.

national list. If there are no perfect matches, the kidney becomes

available to transplant centers in the region from which it

came.

The Emory Algorithm follows these

guidelines but also allows a transplant center to predict which

sensitized patients on the list will be compatible with any

given donor. A five-year study, published in the American

Journal of Transplantation, found the algorithm raised

the kidney transplant rate from 15% to 25% by accurately predicting

which sensitized patients would be compatible with the donor

kidney. In the study, the survival rate for sensitized patients

was almost identical to that of unsensitized recipients—66%

versus 70%.

Immunologists Robert Bray and

Howard Gebel, along with transplant surgeons Christian Larsen

and Thomas Pearson, developed the algorithm. They used a relatively

new technology of single-antigen bead assays. This method analyzes

HLA antibodies more specifically by identifying a single antibody

at a time versus general groups of antibodies. The algorithm

allows immunologists to inform transplant surgeons with a high

degree of confidence whether a kidney from a deceased donor

is a compatible match with a recipient. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|