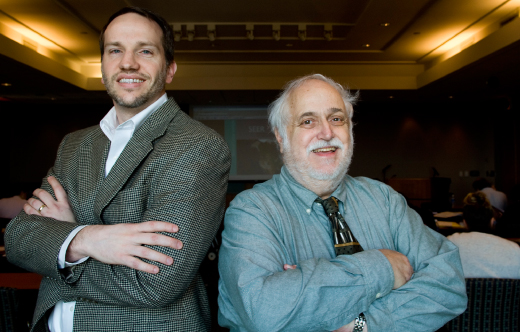

Seers of cancer trends

Epidemiologists Kevin Ward and John Young track cancer statistics in Atlanta and in Georgia to inform research on cancer trends and target groups at higher risk of disease.

By Martha Nolan McKenzie

An Emory data registry informs research to help ensure standard delivery of care and equal treatment for future patients.

|

Focus on cancer |

When patients in Atlanta are diagnosed with cancer, John Young and Kevin Ward don't treat them or even study them individually. Instead, they follow their progress through the Atlanta Surveillance, Epidemiology, & End Results (SEER) registry to identify cancer incidence, mortality, survival, and treatment patterns. Atlanta SEER, which is part of the Georgia Center for Cancer Statistics (GCCS) in the Department of Epidemiology, has tracked all cancer cases in five metropolitan counties since 1975.The registry is part of the wider SEER program, established in 1973 by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) as a primary source of U.S. cancer statistics. Leading public health organizations, including NCI, CDC, and the American Cancer Society, use SEER data to analyze trends in cancer incidence and mortality, develop cancer control programs, measure the impact of prevention programs, and guide health policy decisions.

"SEER provides essential information for tracking the nation’s progress against cancer," says Young, who co-founded the national SEER program while at NCI. Recently retired as director of Atlanta SEER and the GCCS, Young continues to serve as professor of epidemiology.

Cancer experts know well that Atlanta SEER plays a critical role in the overall collection of population-based surveillance data because of the demographics of its registry. "The Atlanta program has been instrumental in helping us assess the cancer burden on the African American population," says Brenda Edwards, associate director of surveillance programs for NCI. "It has also been one of the few data sources from the South. It’s been an important population to complete the national picture."

A rich data environment

The data collected by SEER allows health care experts and policy-makers to spot broad trends. "For example, we’ve seen a large decrease in the incidence of lung cancer, presumably because of anti-smoking campaigns," says Young. "We’ve also spotted some declines in colon cancer, which might be attributable to the five-a-day eating healthy campaign. Conversely, we’ve seen a rise in breast and prostate cancers, perhaps because the population is aging."

Trends identified by SEER, in turn, inform the work of cancer researchers. "Surveillance systems such as ours primarily focus on collecting the data. The real value comes from how researchers use the data," says Ward, who now directs the Atlanta SEER and GCCS and serves as research associate professor in epidemiology. And like Young, Ward also holds a joint appointment in the Emory Winship Cancer Institute.

The registry’s close local ties ensure that its data is put to fullest use. "Certainly, researchers at Rollins take advantage of Atlanta SEER data for their research," says Edwards. "But Atlanta SEER is unique in that it is situated in an academic research-oriented environment, since Atlanta is also home to the CDC, the American Cancer Society, and the Emory Winship Cancer Institute. The data gathered by Atlanta SEER is in a rich environment for research."

For example, researchers may use SEER data to determine if treatment protocols are being met. "If you have stage III colon cancer, you should be followed up with a course of chemotherapy, according to the latest treatment recommendations," says Young. "Researchers may use our data to identify patients with stage III colon cancer and then find out how many, in fact, received chemotherapy. They could then look into why those who did not get chemo did not."

In fact, the population-based nature of SEER data makes it ideal to target disparities in cancer diagnosis, treatment, and survival rates. "We collect detailed information on both patient demographics and the stage of the disease at the time of diagnosis. As such, we can readily identify population subgroups who are being diagnosed at later stages," says Ward. "Those are the areas where you want to target your resources since later-stage diagnosis represents more advanced disease and poorer prognosis."

|

|

||||

Tapping into Medicare

SEER also collaborates with Medicare, linking its registry data with Medicare’s enrollment and claims files. SEER-Medicare data can be used for a number of studies spanning the continuum of cancer control activities. "It opens the door to a wide range of research possibilities, from exploring the cost of medical care to examining the role of co-morbidities in patient treatment and outcomes," says Ward. "Researchers can get a lot more detail than what is collected in registry data because they have access to claims for health services."

A study illustrating the value of using SEER-Medicare data was published in the February 2008 issue of Cancer. The study aimed to determine whether racial disparities in cancer therapy had diminished since the time they had been documented initially in the early 1990s.

Using the linked database, researchers identified a cohort of patients ages 66 to 85 who had a primary diagnosis of colorectal, breast, lung, or prostate cancer from 1992 to 2002. They identified seven stage-specific processes of cancer therapy by using Medicare claims. Black patients were significantly less likely than white patients to receive therapy for each of the four cancers. Researchers concluded that there has been little improvement in either the overall proportion of Medicare beneficiaries receiving cancer therapies or the magnitude of racial disparity.

SEER also conducts Rapid Response Surveillance Studies to study a particular area of interest quickly. In one study proposed by Atlanta SEER, researchers looked at the Gleason score, a measure of prostate cancer aggressiveness and a key determinant of treatment and prognosis. Generally, if a patient scores 7 or higher (range 2 to 10), aggressive treatment is recommended. With a lower score, some patients may elect to monitor their disease to delay invasive treatment that may be unnecessary. Atlanta researchers wanted to know how consistent the Gleason scoring system was.

"Two pathologists independently re-evaluated tissue specimens from hospitals in the metro area," says Ward. "They rescored the slides, and we are evaluating how well their scores match those of the local pathologists who performed the original scoring. The idea is to find out if we need to provide more training for local pathologists and examine the reliability of this data item routinely collected in our registry and used by researchers."

What does SEER data and analysis mean to the person out there battling cancer? "The major benefit is not to the patient who has cancer now, but to the patient who has cancer in the future," says Young. "By collecting this information and looking at the characteristics of patients diagnosed with cancer, you know where to concentrate screening programs because you know what groups are at higher risk. You know what patients are getting state-of-the-art treatment versus those who fall through the cracks. Then you can concentrate your efforts in certain areas to ensure that all patients are treated equally and correctly."