Champions of cancer outcomes

By Pam Auchmutey

Two nationally known researchers channel their expertise to improve cancer outcomes in Georgia.

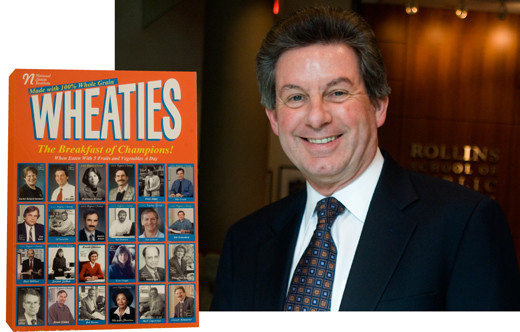

Joseph Lipscomb is the only RSPH professor featured on the front of a cereal box. Formerly a branch chief with the National Cancer Institute (NCI), Lipscomb was one of a select group of NCI staff who championed research initiatives to improve cancer outcomes. Their faces appear on the front of a mock Wheaties box labeled "Breakfast of Champions." The framed box front hangs in Lipscomb's RSPH office, a daily reminder of his efforts to improve cancer quality of care and outcomes.

|

Focus on cancer |

Early analyses have focused on 1,152 breast and colorectal cancer patients diagnosed between 2001 and 2003 in rural Southwest Georgia. Many of the area’s 700,000 residents, black and white, are poor with little or no health insurance. They often live miles away from cancer treatment centers spread across the region.

Thus far, it appears that patients completed treatment at rates comparable to those reported in national studies (about 85% for breast cancer and 67% for colorectal cancer). For patients who dropped out of treatment, about 75% did so because of side effects or other clinical factors. More than 20% of those who stopped cited lack of transportation or social support or other economic barriers as reasons.

An unexpected result

When Lipscomb’s team first analyzed the data, one finding was unexpected: There was no significant difference between whites and blacks likely to begin or complete recommended care for breast or colorectal cancer. In some cases, it appears that blacks were more likely to complete care. Lipscomb’s team is analyzing the data further to see if the finding holds up.

"Our findings represent a significant departure from what has been seen in other studies examining racial/ethnic differences in receipt of cancer care," says Lipscomb. "Virtually all of these studies have focused on urban populations or a mix of urban, suburban, and rural areas. Our Southwest Georgia study is one of the first to examine the clinical and socioeconomic determinants of cancer care in a large rural population."

Researchers and policy-makers who have seen the results were not entirely surprised, Lipscomb adds. "Some have cited anecdotal evidence of strong social networks in black communities, and perhaps more so in rural communities, that could help sustain cancer patients through their treatment."

|

"Our Southwest Georgia study is the first to examine the determinants of cancer care in a large rural population." —Joseph Lipscomb, Professor, Health Policy and Management |

||

Lipscomb is co-leading another study to identify factors that influence whether breast and prostate cancer patients receive guideline-recommended care throughout treatment. The CDC-funded study encompasses seven states. In Georgia, Lipscomb and a team of Emory investigators are examining data for about 2,000 breast cancer and 2,000 prostate cancer cases statewide.

"We are especially interested in identifying what factors explain the substantial variation in who gets quality cancer care," says Lipscomb. "How much of the variation in care patterns is attributable to patient factors such as clinical severity or socioeconomic status? How much can be explained by the type of hospital or physician specialty? Understanding these factors is a first step in designing policies to reduce variations in cancer care in Georgia and the nation."

While with NCI, Lipscomb led the creation of the Outcomes Research Branch, charged with finding better ways to measure the impact of cancer and cancer care on health-related quality of life. His second mandate was to build consensus on standards for measuring and improving quality of cancer care nationwide.

|

|

|||

One result was the Cancer Care Quality Measures Project, sponsored by the nonprofit National Quality Forum (NQF). By 2007, Lipscomb and other project leaders developed a set of measures for breast and colorectal cancer now used nationally. The American College of Surgeon’s Commission on Cancer (CoC), the accrediting body for 1,400 health care organizations, adopted the NQF measures for a pilot project to transform how cancer care data are collected, analyzed, and reported back to providers.

Lipscomb is working with the CoC to conduct the first phase of a Rapid Quality Reporting System (RQRS) pilot at seven hospitals in Georgia. The project seeks to make data on breast and colorectal cancer available to providers in close to real time, speeding up an 18- to 24-month process. If successful, the CoC would likely expand RQRS to include a range of cancers for possible use across the nation.

Men in black

A few years ago, two men wearing black suits visited Kyle Steenland’s office in the RSPH. One of them represented DuPont de Nemours & Company, and the other represented the plaintiffs in a class action lawsuit against the company’s Washington Works plant on the Ohio River. Both men asked Steenland to serve on an independent science panel to determine possible health effects from the release of C8, a chemical used to manufacture Teflon, into drinking water sources for communities in Ohio and West Virginia. The lawsuit resulted when animal studies conducted early this decade linked C8 to liver, pancreas, and testicular cancer and possibly breast cancer.

After the case was settled in 2004, the C8 Science Panel and the C8 Health Project were formed to study possible health effects related to C8. Steenland is part of the three-member panel looking at the overall health of 69,000 people. Panel members are conducting 11 different studies through 2011.

"No one really knows why virtually everyone in the United States has 4 nanograms per milliliter of C8 in their blood," says Steenland, professor of environmental and occupational health. "It may be found in low levels in drinking water in various places. Existing blood levels may have resulted from past exposure to commercial products such as Gore-tex and Scotchguard. It’s a puzzling question."

Steenland has long been interested in studying cancer, formerly as an epidemiologist with the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health and currently as a Georgia Cancer Coalition Distinguished Cancer Scholar in the RSPH. When the CDC called for proposals to study quality of life among patients with prostate cancer, Steenland secured funding to study men in Southwest Georgia through the EPRC and the SWGA Cancer Coalition. It was new scientific territory.

"There’s no standard treatment for prostate cancer," he says. "Men generally don’t die of prostate cancer. But they can live with it for a long time and have serious side effects."

|

"Men generally don’t die of prostate cancer. But they can live with it for a long time and have serious side effects." —Kyle Steenland, professor, environmental and occupational health |

|||

A prostate cancer diagnosis is often stressful for husbands and wives. Men may experience side effects related to urinary, bowel, and sexual function. Some men become depressed as their spouses try to cope.

"We really don’t know a lot about what happens after men get prostate cancer, particularly those living in rural areas," says Steenland. "We’re dealing with an unknown. Why do men choose different treatments, and do they choose them differently in Southwest Georgia? Do different treatments correlate to variations in quality of life? And what factors besides treatment influence how well people do? Spirituality, having a support person, socioeconomic status—all are factors that affect quality of life in an area that’s poor and predominately African American."

Steenland studied 300 men from ages 45 to 75 who were diagnosed with prostate cancer between 2005 and 2008. Local residents where the study subjects lived were trained to collect data by interviewing patients and their wives/support persons, primarily in the patients’ homes. Interviewers also talked with patients’ physicians. Patients were interviewed after their diagnosis and then six and 12 months later. The study also drew data from patient medical records and the Georgia Comprehensive Cancer Registry.

Compared with prostate cancer patients in Atlanta, men in Southwest Georgia were twice as likely to choose external radiation, 1.5 times as likely to choose treatment with implanted radiotherapeutic seeds (known as brachytherapy) plus external radiation, and half as likely to choose surgery or seeds alone.

Reasons for these differences are unclear, Steenland points out. Urologists who tend to recommend external radiation over seeds and surgery, patients who prefer external radiation treatment, or some combination of both may account for these differences.

Steenland also learned that 15% to 20% of patients reported having difficulty understanding their doctors. Patients who were older or who had early-stage cancer chose watchful waiting over aggressive treatment.

Data collection for the quality-of-life study ended late last fall, and Steenland’s team will analyze data for the next several months. "Most quality-of-life studies for cancer go on for at least five years because symptoms and side effects change over time," he says. "I’d like to contact these men again after we know more from our first study."

|

|

||||