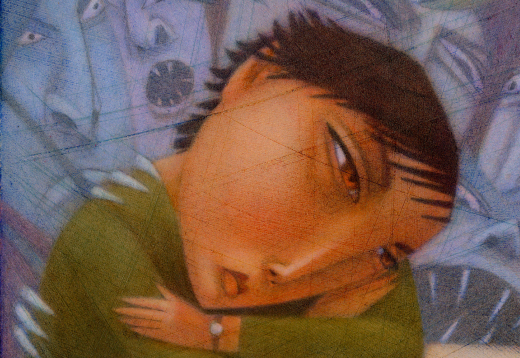

Diving deep inside the brain

Deep brain stimulation offers hope for treatment-resistant depression

By Bill Sanders

For some people with severe depression, what works for everyone else doesn’t work for them. Talk therapy, drugs, and electroconvulsive therapy have given them no relief. But a new treatment may mean that they are not at the end of the road.

While typical therapies for depression usually provide a partial reduction in symptoms, deep brain stimulation has the potential to provide complete remission. Emory psychiatry and neurology professor Helen Mayberg, psychiatrist Paul Holtzheimer, and neurosurgeon Robert Gross are leading a clinical trial to determine whether a pacemaker-like stimulation implant in the brain can give severely depressed patients motivation to function and live a full life.

Mayberg started this research in 2002 with a small sample of patients at the University of Toronto. She moved to Emory to continue the work with a larger group in collaboration with Holtzheimer and Gross.

Some of the first patients treated with deep brain stimulation (DBS) have shown remarkable improvement, researchers say. Though she’s optimistic, Mayberg is quick to caution against inferring too much from the early findings.

“Brain stimulation technology is still quite crude,” Mayberg says. “The implant itself is big, like a pacemaker. I’d like it to be miniaturized, but for now, it’s not. And people need to know that the technology is not proven or generally accepted. The research is experimental.”

While using DBS to treat depression is new, DBS itself is not. DBS was first developed in 1987 and has been approved by the FDA for treatment of essential tremor and Parkinson’s disease.

“We did a proof-of-principle study in Canada on six people who had failed a minimum of four types of treatments for at least two years,” Mayberg says. “These patients had no options except to continue mixing medicine with no real hope that it would work. These people were beyond suicidal. Many people who have this degree of depression are apathetic enough to wish they were dead but have no plan or intent to commit suicide.”

As a rule, the surgery to implant the stimulator is not offered to anyone who has not tried various antidepressant medications and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). And it is only for patients stuck in a major episode of depression, not ones who are chronically up and down.

The Emory team enrolled its first patient in the clinical trial in January 2007. She was a woman in her 40s whose depression had left her so disabled she had to move back in with her parents. She had been treated by a psychiatrist and had tried several medications, as well as ECT, to no avail. Since then, the team has implanted the stimulator in 16 other patients, most of whom have seen at least some improvement.

“There is nothing more gratifying than seeing patients recover who have been this ill,” says Mayberg. “If you’ve been this ill for several years, the world has passed you by. Where do you start when you get your life back? That’s a huge issue for us, and it will take some serious rehabilitation. The stimulator keeps you in a rhythm, but we then have to proceed to retrain them or get them used to the pace of today’s life. It’s just like when you have a hip replacement surgery. You get a new hip, but you still need physical therapy.”

Brian’s story

Brian, who did not want his last name used, was 26 when he became one of Emory’s first deep brain stimulation patients in 2007. He had tried medications and ECT and was on the verge of trying vagus nerve stimulation surgery (VNS) when he decided against it at the last minute. (During VNS surgery, a stimulator is implanted in the chest. It sends electric impulses to the brain via the left vagus nerve in the neck. DBS sends electric impulses directly to the brain.)

His depression started when he was a teenager, and over the years, he was hospitalized a half dozen times in different hospitals. He was no longer on medication.

“From age 23 to 26, I’d been on pretty much everything and tried ECT,” he says. “I couldn’t sleep at night because I’d lay in bed and think of everything I had done wrong that day. I would go to sleep, then wake up around 2 or 3 in the morning, disappointed that I woke up, disappointed that I was still alive.” He’d been in a deep depression episode since at least 2004, when he quit his job because he could no longer function. The depth of his depression was stunning to him.

“All I could do was get out of bed and go to the kitchen. It didn’t matter what I would eat because it all tasted the same,” he said at a recent Emory University class on depression. “I only ate so I wouldn’t end up at the hospital. I would lay on the couch all day in front of the TV, not caring what was on, then go to bed.”

According to both Brian and Holtzheimer, Brian likely would have tried to kill himself if he could have mustered the energy to do so. The depression had drained his energy to the point where walking 50 feet down a hallway would take five minutes and leave him exhausted.

Brian’s depression wasn’t normal, even for depressed people. His was treatment-resistant depression, which occurs in roughly 1% of Americans.

“It’s important to note that depression is not just profound sadness,” Holtzheimer says. “It’s a complex syndrome, a combination of symptoms. Brian has a treatment-resistant major depressive disorder, and our goal for these patients is remission, which means no symptoms. Most treatment is only likely to get a certain percentage of improvement due to the design of the studies. Unfortunately, very little research is being done on treatment-resistant depression, and 20% of the depressed population is resistant to treatment. This form of depression, clinically, is very different from depression that responds to treatment, and we think it is physiologically different too.”

Stimulating the white matter

For most of Brian’s eight-hour surgery, he was awake. Gross, the team’s neurosurgeon, implanted an electrode on each side of the brain. The electrotrodes were connected to a 2- x 3-inch battery unit that was implanted into the chest. The battery unit sent electrical impulses to specific parts of Brian’s brain.

“We test stimulation at four contact points on each side of the brain to assess for positive and negative behavioral effects. We want to know which contact points are optimal for chronic stimulation. This is done in the operating room so we can potentially move the electrode,” Holtzheimer says.

The battery generally lasts up to five years, at which time a 30-to-60-minute surgery is needed to replace it. When the battery dies, patients slowly begin regressing to their depressed state within two to four weeks. Once a new one is implanted, the patient tends to improve rapidly.

Early on in the study, Mayberg and her team—first in Canada, then at Emory—saw signs that chronic stimulation of white matter tissue tracts adjacent to the subcallosal cingulate gyrus (also called Brodmann area 25 of the cerebral cortex) was associated with a marked and lasting remission of depression. Mayberg’s earlier research in patients with treatment-resistant depression patients has shown that their subcallosal cingulate region is overactive. In addition, the region’s connections to the brainstem, hypothalamus, insula, and frontal cortex are linked to changes in sleep, appetite, libido, and cognitive functioning—often characteristic of depressed patients.

The more direct stimulation of DBS is putting patients into complete remission, unlike VNS. While VNS studies also aimed to put patients into remission, their response rates were low. (At present, VNS is the only FDA-approved treatment for patients with severe, treatment-resistant depression.) “Compared with VNS, the response rates with DBS seem higher,” Holtzheimer says. “But DBS studies so far have been preliminary, so it’s too early to adequately make a comparison. Our next step will be longer, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials.”

Brian improves

Within a matter of months, Brian began to feel better. Now, three years after the surgery, he is still in remission. He fights occasional self-esteem issues, but he’s hopeful for the future, feels good, and experiences life’s ups and downs the way they are supposed to be felt, he says.

Brian is evaluated regularly by his Emory team and had to undergo another procedure when the battery in his implant died. “This is an expected event after two or three years,” Holtzheimer says. “That’s one of many reasons we keep tabs on how patients are feeling.”

The Emory team is hopeful that unlike ECT, which isn’t a one-time permanent fix, deep brain stimulation will work for a lifetime for those who respond.

“We want to expand and refine what we started but also learn more about depression and how we can optimize the treatment,” Mayberg says. “My research lab is focused on what goes wrong in the brain that causes depression and how to identify findings from brain imaging that might help us best prescribe a treatment that improves the likelihood of getting well—be it psychotherapy, medication, or in rare cases, DBS. No one should have surgery unless there are no other options. It’s safe and relatively straightforward as far as brain surgery goes, but it is brain surgery. Like I said, though, nothing is more gratifying than seeing patients who were this ill begin to recover.” EM