Miracle Miles

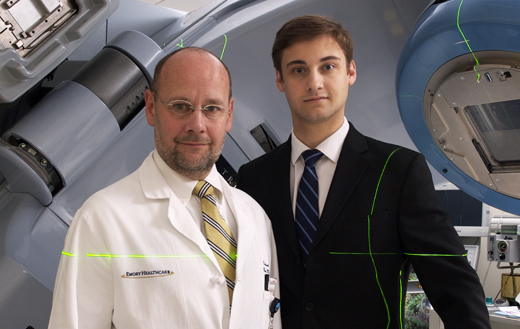

Edmund Waller (left) heads clinical trials at Emory Winship Cancer Institute and once faced the decision of whether to have his son Anthony participate in a clinical trial. Anthony, diagnosed with leukemia at 16, now works in Emory's radiation oncology department.

by Quinn Eastman

With the help of hundreds of volunteers, Emory is on the road to finding new medical treatments, clinical trial by clinical trial.

Early in his career, neurobiologist Don Stein noticed something unusual in studying the behavior of brain-injured rats. After a brain injury, some females seemed to recover promptly while the male rats did not.

Some 40 years later, after much trial and effort, Stein was able to prove that progesterone, a reproductive hormone, explained why. The hormone seemed to slow or block damaging chemicals released after brain injury, protecting brain cells from destruction. Both male and female rats with brain injury developed less brain swelling and recovered better when they were treated with progesterone soon after the injury.

|

“The major reason why studies fail is that not enough people are enrolled. We’re losing potentially valuable treatments because they can’t be adequately tested.” —Carlton Dampier, medical director, Emory’s Office for Clinical Research |

||

But would progesterone work similarly in human brains? It was an important question because there had been no new effective treatment for traumatic brain injuries in four decades.

Emory emergency medicine physician David Wright led a three-year pilot study to begin to answer that question. Called ProTECT (Progesterone for Traumatic Brain Injury-Experimental Clinical Treatment), the study tested the safety of giving progesterone to 100 people soon after they experienced a traumatic brain injury. The results were encouraging: not only does the treatment appear to be safe but it also cuts the risk of death by 50% and reduces subsequent disabilities.

This year, Emory hopes to embark on a large-scale clinical trial to test whether the promising results hold up with a larger patient sample. With the planned collaboration of 17 university partners around the country, the phase III trial will be led by David Wright at Emory. Investigators are planning to enroll 1,140 people, beginning in the fall of 2009.

The progress for treatment of traumatic brain injury is just one demonstration of the value of clinical trials. In fact, clinical research is the only way that researchers can judge whether a treatment developed in the lab has a high probability to work in people or that an effective procedure, sometimes discovered by accident, can be replicated in a larger population with similar good results.

Despite unknown outcomes and some studies that fall short of expectations, clinical trials have a track record of producing life-saving cures, sometimes nothing short of miraculous. They also have yielded new medical devices, from instruments for laser surgery to pacemakers and artificial joints.

In fields from neurology to cancer, demand for participants in clinical trials is increasing. The Association of Clinical Research Professionals reports that industry spending on patient recruitment has doubled across the nation in the past five years. Yet few patients with serious illnesses participate in clinical trials—in fact, less than 5% of cancer patients do so, according to the National Cancer Institute.

One reason is that historically clinical trials often have been unavailable where patients lived, clustered in academic medical centers. Emory is working to offer more clinical trials to patients outside of the metro Atlanta region. In November 2007, Emory Winship Cancer Institute and the Georgia Center for Oncology Research and Education (Georgia CORE) opened the first statewide clinical trials for cancer in Georgia. The study allows the collaboration of investigators from an academic medical facility with community-based oncology practices and other academic centers to enroll patients in a clinical trial for early-stage breast cancer.

Medical research needs people to say yes to participation in clinical trials more than ever, says Carlton Dampier, medical director of Emory’s Office for Clinical Research. “The major reason why studies fail is that not enough people are enrolled,” Dampier says. “We’re losing potentially valuable treatments because they can’t be adequately tested.”

Why patients say yes

At Emory, hundreds of people agree to take part in clinical trials each year. Currently, Emory is running more than 1,340 clinical trials sponsored by the NIH and other government and private organizations. At Winship alone, more than 500 patients were enrolled in clinical trials in 2008.

Some of the university’s studies are in collaboration with partners, such as the Atlanta VA Medical Center, Georgia Tech, Grady Health System, and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta. These studies approach health from a wide range of treatment and prevention strategies. Clinical trials now under way are evaluating the effects of a Mediterranean diet on oxidative stress, whether calcium and vitamin D can reduce the occurrence of colon polyps, a new surgical technique for adult congenital heart disease, and the effect of B12 supplements on Parkinson’s disease.

Because the outcomes of clinical trials are uncertain, it’s not always easy for patients to decide to sign on. What if the treatment being tested doesn’t work or has serious side effects? Will they even get the treatment or a placebo if they decide to participate?

|

Retired engineer McCamie Davis and his wife, Starla, are taking part in a clinical trial to see if a vaccine can slow progression of his Alzheimer’s disease. |

|||

Recently retired engineer McCamie Davis agreed to take part in a trial at Emory to see if a vaccine could slow progression of Alzheimer’s disease. “The doctors explained it very thoroughly,” Davis says. “As long as you were in the trial, you could not know if you got the vaccine or not. But at the end, when they tally up the results, you could get the real vaccine if it turns out to be good.”

At the moment, Davis is still able to make such decisions. As his disease progresses, however, it may impair his ability to do so. That’s why this particular clinical study, and others like it, requires the agreement and participation of a caregiver—in Davis’s case, his wife Starla.

“Of course, part of the reason we wanted to participate is that we hope there will be improvement for him,” Starla Davis says.

Even if they don’t benefit from a miracle themselves, many patients choose to participate in clinical trials partly because they think they can further medical science and help others. “Many of the families we work with talk about leaving a lasting legacy,” says Janet Cellar, a clinical research nurse at the Emory Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center.

Removing roadblocks

One of the first lessons health care students learn is, do no harm. Clinical trials also follow this mandate by putting precautions in place on behalf of participants. Emory’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) reviews, approves, and monitors all trials to ensure that volunteers are protected from needless risk. The IRB committee also makes sure that participants are protected in accordance with federal regulations and that they fully understand the clinical trials process through informed consent.

“Anything less than full and accurate information could be considered deception,” says Aryeh Stein, co-chair of Emory’s IRB and a global health researcher in Emory’s Rollins School of Public Health.

Although Stein and his colleagues have tried to simplify the language of consent forms, federal regulations and legal requirements make a typical consent form lengthy— usually a dozen pages or more. As long as a decade ago, a federal review concluded that the consent process had become “a disclaimer for institutions rather than information for the participant” and “may be inappropriately deterring individuals from participating.”

Emory cardiology fellow and bioethicist Neal Dickert is working with cardiology colleagues Habib Samady and Alex Llanos to simplify the informed consent process for an ongoing clinical trial in which they are testing a modification for restoring blood flow to the heart after angioplasty.

During angioplasty, doctors use a balloon at the end of a catheter to open up the obstructed coronary artery and restore blood flow to the heart. However, recent evidence supports the idea that rapid restoration of blood flow may damage the heart muscle as much as the original disruption of flow. Llanos and Samady are testing a modified “stuttering” procedure in which the balloon is precisely controlled to inflate and deflate several times. The goal is to allow blood back into the heart gradually to prevent damage.

The Emory researchers are among the first to test this procedure, known as post-conditioning. They will use MRI and echocardiography to assess heart muscle damage in patients treated with standard angioplasty and those treated with the post-conditioning approach.

Although the study began with regular consent forms, Dickert and colleagues have developed a shorter form, just two pages, and an oral script for doctors to follow in obtaining permission from potential participants. During 2009, the study will make a switch to the shorter forms, and Dickert plans to interview patients while they are still in the hospital to assess whether the new process results in better understanding of important facts about the study and improved satisfaction with the consent process.

The outcome of the cardiology study is unknown, and despite its early promise, so, too, is that of ProTECT. That is why clinical trials, with all their challenges of oversight and informed consent and patient recruitment, remain vital. They are the vehicles by which these unknown results become known. They hinge on the imagination of innovative researchers and the participation of forward-thinking volunteers. They mark the long road to the next small step in managing a chronic disease, to testing a promising cure, and sometimes, even finding a medical miracle.