Life-changing discoveries on the medical frontier

FDA approval for new transplant drug

|

For the past 20 years, kidney transplant recipients have faced a cruel paradox. To stave off immune rejection of their new kidneys, they must take drugs that gradually destroy kidney function.

Emory transplant specialists Chris Larsen (right front) and Tom Pearson have been leading the development of an alternative drug that can control the immune system while having less toxic side effects. In June 2011, belatacept—the result of the researchers long collaboration with Bristol-Myers Squibb—received FDA approval. Belatacept has the potential to simplify the medication regimens of kidney transplant recipients because it can be given every few weeks in contrast to standard drugs, which must be taken twice a day.

“Our goal is to achieve a normal life span for kidney transplant patients and have them survive dialysis-free,” Larsen says. “We believe belatacept can help us move toward that goal.” Belatacept also is being tested at Emory in clinical trials for liver and pancreatic islet transplant.

Progesterone as pediatric cancer treatment

|

New research findings from Emory suggest that progesterone may be effective against neuroblastoma, a form of cancer affecting small children.

Already progesterone is being tested in emergency departments across the country in a phase 3 clinical trial for traumatic brain injury—thanks to pioneering research by Emory neuroscientist Don Stein. In investigating how to possibly enhance progesterone’s effectiveness, Fahim Atif, a colleague in Stein’s laboratory, observed that it could protect healthy neurons from stress but kill tumor cells. The findings, that high doses of progesterone can kill neuroblastoma cells while leaving healthy cells unscathed, appeared in Molecular Medicine (summer 2011).

Progesterone’s effects on cancer are known to be complex. Large-scale studies have shown that hormone replacement therapy with combined estrogen and synthetic progestins can increase the risk of heart disease and breast cancer. However, there may be differences between progesterone, the natural hormone, and synthetic progestins.

More research is necessary to determine the optimal dose, how long treatment should last, and if progesterone should be used alone or in combination with radiation or chemotherapy. Emory scientists are also exploring whether it can stop the growth of other brain cancer types such as glioblastoma and astrocytoma.

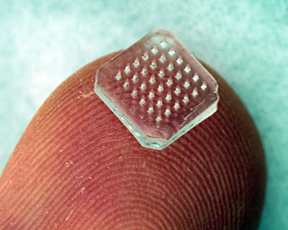

Microneedle apps

|

The right stuff delivered to the right place is the goal that Emory and Georgia Tech researchers have in mind in exploring the applications of microneedles.Not only can tiny needles supply medication directly into the eye, they allow vaccines to meet up with cells in the skin that drive good immune responses in H1N1 flu and other strains.

Although intramuscular injection is a standard mode of vaccine delivery, it may not be the most efficient. The muscles have a low concentration of cells needed to activate immune signals, called antigen-presenting cells, says Emory immunologist Ioanna Skountzou. In contrast, the skin contains a rich network of antigen-presenting cells.

Vaccination by a microneedle patch appears to ensure that immune protection lasts a long time. In contrast, mice that received an intramuscular injection of flu vaccine had extensive lung inflammation and 60% less antibody production against the virus. Mice that were vaccinated with microneedles maintained high levels of antibody production, with no signs of lung inflammation when challenged with homologous influenza virus six months after vaccination.

Microneedles offer other logistical advantages, such as low cost, small size, and simplicity that might enable people to vaccinate themselves, says Georgia Tech’s Mark Prausnitz, who developed the technology.

For ophthalmology researchers, a long-standing goal has been to deliver medication to the back of the eye in a selective and minimally invasive way. In April, Henry Edelhauser, former director of research at the Emory Eye Center, and Prausnitz were awarded a patent for this application of microneedle technology.

Many patients with age-related macular degeneration have injections on a regular basis. Because the microneedle apparatus is so much smaller than the needles used to inject medicine into the eye, the patient may experience less discomfort. The same technology could be used to inject medication directly into the eye for other ocular conditions, such as glaucoma, eliminating the need for daily drops.—Quinn Eastman