Full potential.

Emory's Down Syndrome Center is showing what a child with an extra chromosome can do.

by Rhonda Mullen, Photography by Jack Kearse

Meet the Mulligans.

The father, Paul, is an executive at The Coca-Cola Company, and the mom, Adrienne, a community activist and tall Irish beauty. Their two boys, Hugo and Kyle—ages 7 and 6—are boisterous but well-mannered, shaking an adult’s hand and saying “Nice to meet you” before they thunder outside to play. The baby, Sara Kate, is a loveable and cuddly 3-year-old, who has her mother’s good looks.

But Sara Kate has one additional attribute—an extra copy of chromosome number 21. This condition is called trisomy 21 but is more commonly known as Down syndrome (DS). Around 250,000 families nationwide have a child with DS, which occurs in 1 of 691 births.

The additional genetic material causes what Adrienne Mulligan calls “a perfect storm of circumstances.” These children have developmental delays, and they often experience hypotonia (low muscle tone), congenital heart defects, respiratory challenges, and gastrointestinal abnormalities.

However, with early interventions, many children with DS now are overcoming these obstacles to live rich and full lives up to age 50 and beyond. The Down Syndrome Center at Emory helps more than 200 children with DS each year, providing clinical care, access to research, and connections to community resources to allow these children to reach their fullest potential.

This is one of the reasons that the Mulligans say they are grateful to be in Atlanta.

From clinic to community

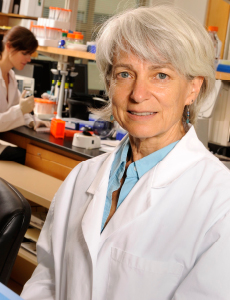

Pediatrician Jeannie Visootsak, shown above with Emma and Daniel Harman, works with children with Down syndrome (DS) and their families to boost development and potential. She also collaborates on research with Emory geneticist Stephanie Sherman(below), who has amassed the largest DS database in the country. Current Emory studies are examining the variations that can result from having an extra chromosome 21 and identifying factors that may lead to a congenital heart defect in people with DS. |

Jeannie Visootsak—or Dr. Jeannie, as patients call her—is a developmental behavioral pediatrician, who directs the Down Syndrome Clinic that opened at Emory in 2003. The clinic works with 15 hospitals in the Atlanta metropolitan area and is often the first specialty care for DS that local families encounter.

“Our goal is to form a long-term relationship with the children and parents, help them look beyond the diagnosis, and be an advocate for them,” Visootsak says. At the beginning, parents “may be overwhelmed and unsure of which direction to take. We start talking about development right away and what parents can do to help their children reach their full potential.”

The first visit with a family begins with a review of the chromosome studies and sharing general information on DS. Children receive a full physical and developmental screening as well as a review of DS health care guidelines, specifically medical issues, from vision and hearing to thyroid and cardiovascular function. They are given referrals to the state’s early-intervention program for physical therapy and to medical specialists for particular concerns.

“Each child is an individual with different strengths and challenges,” says Visootsak. “But one thing is a given for all. They have a wide range of developmental delay. So early intervention is key.”

Some 20% of the clinic’s population is Hispanic, and the clinic provides a full-time Spanish translator for those patients and families.

Just as important as the clinic’s referrals to physical and developmental specialists is putting families in touch with community resources like the Down Syndrome Association of Atlanta (DSAA), says Visootsak, who describes the DSAA as “the area’s premier DS organization.” A partner of Emory’s DS clinic, the DSAA enhances the lives of people with DS through support, education, advocacy, and programs. It provides programs for new and expectant parents and links them to support groups and early-intervention programs like the one at Emory. In fact, says Visootsak, the DSAA was instrumental in helping get the clinic started, and its enthusiastic support has helped Emory’s clinical and research efforts in DS continue to grow.

The largest database of the smallest chromosome

That research takes place in the Emory medical school’s Department of Human Genetics, where geneticist Stephanie Sherman has spent more than two decades studying the causes and consequences of DS.

Over the years, she has amassed the largest DS database in the country, thanks to children and families who have participated in studies at Emory. In one such study, the Atlanta Down Syndrome Project, done in collaboration with the CDC from 1989 to 1999, researchers interviewed and collected medical information and biologic samples both from families with an infant with DS and controls without DS in the five-country metro Atlanta area. The goal was to understand why the chromosomal error occurred and to look at the consequences of having an extra chromosome 21.

From 2000 to 2004, the study expanded to additional sites around the country to become the National Down Syndrome Project—with Emory leading the largest multi-site, population-based study of DS to date. Again the goal was to identify the molecular and epidemiologic factors that lead to the genetic error and packaging of an extra chromosome as well as to identify risk factors for DS-associated birth defects. The participants included 1,215 families who had a child with trisomy 21 and 1,327 families who had a child without DS. All of the children had been born in the same geographic region.

“We wondered when during the formation of an egg or sperm does the chromosomal error occur and why is the age of the mother such a strong factor that influences this error,” says Sherman.

The researchers began using genetic variants along chromosome 21 in the parents and the child with DS to collect information on the timing of the error—where it occurred during meiosis (a special type of cell division that happens during formation of the egg or sperm). They also looked at patterns of recombination, the exchange of chromosome material among pairs of chromosomes. From model systems (yeast, fruit flies, and mice, to name a few), they knew that recombination was an important process to help stabilize the chromosome pairs during meiosis.

Meiosis occurs in two stages, and the researchers found that the chromosome error in eggs could occur at either stage and that more of the oldest moms had errors at stage 2. “More than anything, the study emphasized the complex association between advanced maternal age and chromosome 21 errors during meiosis,” Sherman says.

What now?

While continuing the work on the causes of the error leading to trisomy 21, current investigations are focusing on understanding the variability that results from having an extra chromosome 21. Why, for example, do only some children with DS have congenital heart or gastrointestinal defects? And what accounts for the large range of cognitive abilities among children with DS? The epidemiologic databank of interviews and clinical information along with a large biorepository of cell lines and DNA continues to be a major source for researchers trying to answer these questions.

Sherman hopes that targeted drug therapy and behavioral and educational interventions will soon become available to improve cognitive learning abilities for those with DS. “Researchers have seen that drugs are working in animal models of DS to restore balance in the activities of the neurons in the brain and how they interact with each other,” she says. “The question is, will they improve behavior and cognition in humans?”

Currently, the largest DS study at Emory (in collaboration with the Sibley Heart Center of Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta and other national sites) is seeking to identify genetic and environmental factors that influence the susceptibility for congenital heart defects in people with DS. The ethnically diverse study conducted by Emory has shown that the risk for atrioventricular septal heart defect (AVSD) is twice as high in African American participants and half as high in Hispanic participants as compared with Caucasians. Researchers are now trying to understand these differences to learn more about AVSD.

Complementing that effort, Visootsak is leading an NIH study to examine the neurodevelopmental outcomes of children with DS who have congenital heart defects, in particular AVSD. As these children increasingly survive cardiac surgery and live longer, the researchers want to better understand their early developmental trajectories (cognitive, motor, language, and social) to design better early interventions to maximize potential.

Skating to acceptance

The baby of the family, Sara Kate always has enjoyed being the center of attention. Her mom, Adrienne, wants to spread the love and resources that her daughter enjoys to Atlanta families with DS through the opening of a GiGi’s Playhouse here this fall. |

Adrienne Mulligan follows results of studies like these like a hawk. She regularly attends educational conferences and research sessions about trisomy 21. Right after Sara Kate’s birth, she decided to get as much education as she could to support her daughter.

She watched a determined Sara Kate struggle with her first baby steps and early walking, which took more energy than Hugo or Kyle had needed because of low muscle tone. She insisted that Sara Kate be tested for sleep apnea, which she turned out to have—as often is the case for children with DS, according to Mulligan. Each week, the littlest Mulligan goes to see physical, occupational, and speech therapists, and the results are paying off. She is excelling in her school program for 3-year-olds.

Adrienne Mulligan is just as tireless in her efforts to spread what she has learned to help all children with DS. She and her husband founded the SKate Foundation—named for Sara Kate—which has a three-fold mission: to publish and distribute a summary of the basic issues that almost all babies with DS face, conduct clinical trials which identify early interventions that work, and reach more families by supporting the opening of GiGi’s Playhouses throughout this country and beyond. In fact, funds raised at the foundation’s inaugural gala are making possible the opening of a GiGi’s Playhouse in Midtown Atlanta this fall. The Atlanta playhouse will work to raise awareness about DS and empower families through free programs for occupational, physical, and speech therapy as well as free tutoring in literacy and math. The Emory Down Syndrome Center received the Playhouse’s first leadership award that honors Visootsak.

“Our vision is to see a world where individuals with DS are accepted and embraced in their families, schools, and communities,” says Mulligan. Of her daughter, Mulligan hopes that Sara Kate has options. “I want her to have the same opportunities as my sons or anyone else on the block.”

Emory’s clinic staff share that same passion to have children with DS reach their fullest potential. “We’re here to help them get the most out of life,” says Visootsak.—EH

|

Web Connection: For more information on the Emory Down Syndrome Center, see genetics.emory.edu/DSC. For community resources, visit the Down Syndrome Association of Atlanta at atlantadsaa.org, the SKate Foundation at theskatefoundation.com, and the new GiGi’s Playhouse in Atlanta at gigisplayhouse.org/Atlanta. |