The flu patch

|

The small prick that comes with your flu vaccination might be getting a whole lot smaller.

Skin patches containing microneedles have proven as effective as traditional hypodermic needles in delivering vaccine and preventing influenza in mice. These patches are more convenient, less painful, and less costly than regular needles, and researchers from Emory and Georgia Tech believe they will increase vaccination coverage as a result. Their research is published in the April 2009 issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and the Public Library of Science One (March 10, 2009).

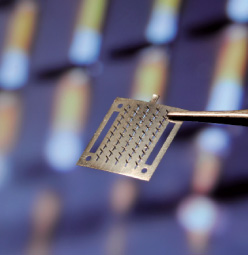

The way the patches work is straightforward: they contain tiny stainless steel microneedles that are covered with inactivated flu virus and pressed into the skin, where the vaccine dissolves after a few minutes.

In their research on mice, the scientists immunized two groups of rodents, one with the microneedle patches and the other with hypodermic needles, and they exposed both groups to a high dose of influenza. All of the mice in the vaccinated groups survived, while those in a control group of unvaccinated mice did not.

In addition to the effectiveness of the flu patches, "vaccine delivery into the skin is desirable because of the skin’s rich immune network," says Emory microbiologist Richard Compans.

Even though it stimulates the immune system and is effective in patients over 60, the technique of delivering flu vaccine directly to the skin has not been widely used. The reasons? It was inconvenient and required highly trained personnel to deliver the vaccine.

Delivery via microneedles changes that. Researchers say that the delivery system is so easy that patients themselves may be able to administer it. The small size of the microneedles also enables ease of transport and storage, making them ideal for use in developing countries. And finally, a format of one-use patches halts accidental re-use of hypodermic needles.

The study team has been working since the mid 1990s to develop a microneedle technology that delivers drugs and vaccine painlessly through the skin. Its next steps will involve additional testing in other animal models, such as guinea pigs and ferrets, before starting tests in humans. More studies are needed to determine the minimum vaccine dosage needed.

The work is complemented by a $32.8 million grant from the NIH to Emory and the University of Georgia to support a center on influenza pathogenesis and immunology research. The center focuses on improving the effectiveness of flu vaccine by studying how influenza interacts with its host and how flu viruses are transmitted. —Stone Irvin