In many ancient cultures, the heart

was considered the seat of the soul.  Some would say the soul of medicine at Emory resides in the heart as well. The treatment of heart disease has been a keystone of clinical excellence both

Some would say the soul of medicine at Emory resides in the heart as well. The treatment of heart disease has been a keystone of clinical excellence both

before and after The Emory Clinic was

formed in 1953. As a result, the Emory

Heart Center is world renowned in

several areas of heart disease treatment

and diagnosis and has been ranked

among the top 10 heart centers in the

United States for the past 11 years. The

distinctions, discoveries, and landmark

innovations just keep on coming.

Also:

Keeping pace

Broken hearted

Tools of his trade

By the book

Heart-stopping moment

If we work together to create something faster and better than either of us individually could do, then we all win, and most important, the patient wins.

We're going to be aggressive about getting our message out about the need for heart attack patients to have access to angioplasty because the lives of patients are at stake.

Emory has served as a seeding ground, training 85% of the practicing cardiologists and heart surgeons in Georgia.

Just the facts

Heart care at Emory

Emory Heart Center (formed in 1993 to coordinate Emory's heart care under one umbrella) encompasses all cardiac services and research at these locations:

- Andreas Gruentzig Cardiovascular Center of Emory University

- Carlyle Fraser Heart Center at Emory Crawford Long Hospital

- Division of cardiothoracic surgery

- Emory electrophysiology service

- Emory Heart Failure Center

- Adult congenital heart disease program

- Outpatient cardiology at The Emory Clinic

Other affiliations

- Grady Memorial Hospital

- Atlanta VA Medical Center (VAMC)

- Children's Healthcare of Atlanta

Patient encounters

- Almost 81,000/year, not counting teaching affiliates

Grants/clinical trials

- >$10 million/year in cardiology research awards

Board-certified specialists:

- 39 cardiologists

- 9 cardiothoracic surgeons

Procedures (2002)

- 1,667 bypasses (on and off pump)

- 225 valve replacements and repairs

- 7,000 diagnostic and interventional catheterizations

- 1,400 electrophysiology studies and ablations

- 500 implanted cardioverter defibrillators (ICD) and ICD generator replacements

Residents and fellows

- 197 internal medicine residents (largest program in the nation)

- 54 cardiology fellows

- 12 cardiothoracic surgery residents and fellows

Innovations

- Angioplasty

- Antioxidant research

- Authored the bible of cardiology, The Heart

- Cardiac catheterization lab (first in Georgia)

- Coronary bypass (first in Georgia)

- Digitalis for children (first in nation)

- Dual-pump ventricular-assist device (first in Georgia)

- Heart pacing and resynchronization

- Heart transplant (first in Atlanta)

- Hybrid coronary revascularizations

- Implantable defibrillator (first in Georgia)

- Implantation of a biventricular pacemaker(first in Georgia)

- Nonsurgical mitral valve repair

- Off-pump triple bypass surgery (first in world)

- Pediatric heart transplant (first in Georgia)

- Stent implant (first in nation)

Kudos

- One of the birthplaces of modern interventional cardiology

- Ranked in the top 10 heart centers in the nation by US News & World Report (the only heart program in Georgia included in the top 50)

- Trains 85% of practicing cardiologists and heart surgeons in Georgia

Also:

Keeping pace

Broken hearted

Tools of his trade

By the book

Heart-stopping moment

By Valerie Gregg

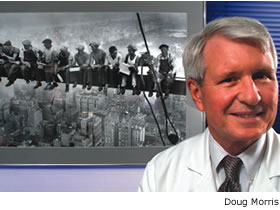

The people in Doug Morris's photo are not afraid. Wearing overalls and work boots, they sit nonchalantly on a beam about eight inches across, their feet dangling loosely a quarter mile over the 1930 New York City skyline.  Thoughtfully chewing sandwiches between casual conversation, they lean on each other, apparently unconcerned with the vast abyss below them. After lunch, they go back to work, walking the balance beam as easily as they sat down on it. Every day, they work together to build a landmark, beam upon beam, brick upon brick. The result of their collaborative labor -- the Empire State Building, highest skyscraper on the planet, the first of its kind.

Thoughtfully chewing sandwiches between casual conversation, they lean on each other, apparently unconcerned with the vast abyss below them. After lunch, they go back to work, walking the balance beam as easily as they sat down on it. Every day, they work together to build a landmark, beam upon beam, brick upon brick. The result of their collaborative labor -- the Empire State Building, highest skyscraper on the planet, the first of its kind.

The Emory Heart Center was built in much the same way, with cardiologists and surgeons working together in uncommon ways to make Emory an international center for the treatment of cardiovascular disease. The path of medical innovation can be risky and rough, but for Georgians with heart disease, the rewards have been great. Ideas considered outlandish in the not-so-distant past are now outpatient procedures performed every day.

"The excellence of the Emory Heart Center is a continuum that began with great insight and great people going way back," says Doug Morris, director of the Emory Heart Center. "Emory has been blessed with good cardiology for years. Cardiology has always been the core of medicine at Emory -- the key, in fact, the cornerstone."

The Emory Heart Center was formed in 1993 to help foster collaboration and coordination among the many aspects of heart disease treatment and diagnosis under the Emory umbrella. It encompasses the Andreas Gruentzig Cardiovascular Center of Emory University (based at Emory University Hospital), the Carlyle Fraser Heart Center at Emory Crawford Long Hospital, the division of cardiothoracic surgery, the Emory electrophysiology service, the Emory Heart Failure Center, the adult congenital heart disease program, and outpatient cardiology at The Emory Clinic. For 11 years, it has been ranked in the top 10 heart centers in the nation by US News & World Report. In 2003, Emory's program in heart and heart surgery was ranked seventh -- the only heart program in Georgia included in the nation's top 50.

What makes the "heart" of Emory different from -- and better than -- most other heart centers around the country? And what makes it a model for other specialties at Emory?

Transcending "politics" within the academy -- traditional turf wars between medical specialties and departments -- has been key, says Michael Johns, CEO of the Woodruff Health Sciences Center. Johns, in fact, has made interdisciplinary collaboration the goal of virtually every corner of the health sciences center, from cancer to public health, basic science to the clinics, and including faculty and staff.

Since its inception, the heart center has worked toward scientific advances that directly benefit patients. Emory surgeons and cardiologists have helped develop some of the most cutting-edge technology and treatments for heart disease in the world. They now provide patients with the most modern care available anywhere. And international stars on the Emory faculty are teaching Emory medical students, residents, and fellows to follow in their footsteps. Doctors travel here from around the world to study the latest procedures and techniques from the people who pioneered them. The list of innovations in heart care at Emory is extensive and continues to grow.

But all scientific innovation is accomplished on a continuum, says Morris. It is a process, with each discovery rooted in those that have come before.

Shifting paradigms

Times have changed dramatically since cardiologist Morris joined the Emory faculty in 1975.

"We didn't even know what caused a heart attack then, and we couldn't stop it once it started," says Morris. "We put heart attack patients in the hospital and watched and waited. We dealt with complications as they arose. All we knew was that a heart attack was somehow associated with a clot in a coronary artery. Once a clot was established to be the culprit, the initiating event, we began efforts to interrupt the process, to disintegrate the clot and re-establish blood flow. The course of this illness was altered forever. Now we can stop a heart attack in its tracks and avoid the complications. The progress has been amazing."

One of the most dramatic changes in cardiology occurred in 1977 in Zurich, Switzerland, where cardiologist Andreas Gruentzig invented angioplasty. He inserted a catheter into a patient's clogged coronary artery and inflated a tiny balloon, restoring blood flow to the heart. Emory cardiologists John Douglas and Doug Morris traveled to Zurich to learn the technique from Gruentzig and in 1980, and with the help of other cardiologists, performed the first angioplasty at Emory. Later that year, Douglas helped convince the dynamic cardiologist to come to Emory.

"Gruentzig was a world-class personality," says Douglas. "He was a very talented, persuasive person. He generated a lot of enthusiasm among colleagues and could persuade anyone to back his ideas. That was instrumental in the early days because to do a pioneering procedure like this, you had to have the support of your surgical colleagues. The surgeons had to stand ready to take over with bypass surgery if angioplasty failed."

This unusual collaboration between cardiology and cardiac surgery - natural competitors in the private health care market - goes way back at Emory. And it is precisely because of this collegial collaboration that pioneering cardiac surgeon Thomas Vassiliades came to Emory this past fall from a lucrative private practice. Vassiliades is an international star in endoscopic, minimally invasive cardiac bypass surgery, and he says the Emory environment is necessary for treatment advances like his to flourish.

"Many institutions are bogged down with a lot of internal competition," he says. "This kind of collaboration is a political hurdle that many places just can't pull off. Taking two disciplines that are most often fierce competitors - cardiologists for angioplasty versus surgeons in favor of bypass surgery - is not easy. Neither one can create the best product for the patient by staying in their own corner. If we work together to create something faster and better than either of us individually could do, then we all win, and most important, the patient wins.

"We're making things happen here. We're not waiting to see where the paradigm shifts -- we're creating the shift.

"I see my bigger focus as helping create collaborative solutions so we can go somewhere we haven't been before. We can still compete against other academic medical centers but not each other. We're partners. That's the bigger picture."

Emory cardiologists and heart surgeons are now at the forefront of the next generation in heart disease treatment -- minimally invasive surgery and interventional techniques that cause as little trauma to patients as possible. They are constantly developing and refining new tools and techniques.

For patients, the most traumatic aspect of traditional coronary artery bypass surgery is having their chests opened like a clam shell. Vassiliades hopes to make that aspect of cardiac surgery a relic of the past. "Open heart surgery is barbaric," he says. "Prying open a patient's chest is not pretty. It hurts a lot."

Vassiliades is a leader in developing endoscopic surgery techniques for cardiac bypass surgery. He has developed specialized robotic tools to help him operate through incredibly small incisions between the ribs. This technique, called endo-ACAB, is probably the most minimally invasive bypass surgery available anywhere. Patients who undergo endo-ACAB are usually in the hospital only two or three days and return to work in two weeks, as opposed to a week in the hospital and two to three months out of work.

Vassiliades is one of only a few surgeons in the country who perform it. Patients are not hooked up to a heart-lung machine during this procedure, and the heart continues to beat. During traditional bypass surgery, the heartbeat is stopped and blood is pumped through a heart-lung machine, the root of many complications and deaths associated with this procedure.

Now Vassiliades and Emory interventional cardiologists have teamed up to offer patients the best of each of their specialties. Their procedure is called hybrid or integrated coronary revascularization, and Emory is one of only a few medical centers anywhere performing it.

In the hybrid operation, Vassiliades performs endoscopic cardiac bypass surgery. Then a cardiologist performs angioplasty on remaining blocked cardiac arteries and installs stents that emit a steady stream of a drug that prevents restenosis, the renarrowing of the cleared artery after angioplasty.

Although this hybrid procedure has been performed only in a limited group of patients, it holds tremendous promise.

It is ironic that one of the most promising innovations in the treatment of heart disease today combines angioplasty with bypass surgery in the same hospitalization. Bypass and angioplasty have competed in both the financial marketplace and the marketplace of ideas for the title of most effective. Which is truly better? The answer, says Douglas, depends on the patient, which arteries are blocked, and the severity of the blockages.

Who's on first?

New procedures to treat heart disease should always be based on well-established science and concern for the patients' well-being, says cardiothoracic surgeon Joe Craver, who has pioneered many surgical innovations during his career. "Being first isn't always so important," he says. "You can be first and then have a poor result with a procedure. What's important is to do the research and gain appropriate experience. Then you may very likely be among the first to do something new that dramatically benefits patients."

There is no question that Emory physicians have done the research and gotten the experience where angioplasty is concerned. Emory cardiologists have performed more than 35,000 coronary angioplasty procedures since Andreas Gruentzig performed the first angioplasty in Switzerland. After he joined the Emory faculty in 1980, Gruentzig worked with Emory cardiologists to refine and study the technique. During that time, he taught hundreds of cardiologists from around the state and the world how to perform it.

That same spirit of sharing knowledge meant to benefit mankind continues today throughout the Emory Heart Center.

As far as advertising goes, Emory Healthcare doesn't need to rely on technicalities or semantics, says Una Newman, senior director of marketing for Emory Healthcare. A new advertising campaign for Emory Healthcare is aimed at providing patients with information that will best ensure their survival of a heart attack. "We're going to be aggressive about getting this message out because the lives of people are at stake," she says.

For the past decade, debate has raged over whether thrombolytic drugs or angioplasty is better for those who have suffered a major heart attack. A groundswell of research now points to better survival for people who receive angioplasty as the initial treatment of a heart attack. Major scientific journals and the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology have recommended changing the standard of treatment for severe heart attacks to angioplasty rather than thrombolytic drugs whenever possible.

But not all hospitals are equipped to offer patients emergency angioplasty. Emory University Hospital (EUH) and Emory Crawford Long Hospital (ECLH) both offer the procedure, 24 hours a day, seven days a week. EUH is the only hospital in DeKalb County that offers it. Morris encourages community physicians to pay serious attention to what is now considered a definitive conclusion backing the superiority of angioplasty over clot-busting drugs.

"When emergency services are confronted with patients suffering heart attacks, we hope they will send them for specialized care to Emory or another hospital experienced in angioplasty," Morris says. "That is the optimal way to ensure them the best chance at survival and recovery."

Morris points out that appropriate triage for heart attack patients requires "in the field" ECGs, which means that ambulances need to be able to transmit ECG information to a hospital while in transit, to help physicians determine sooner whether the patient is indeed suffering from a heart attack or indigestion.

One hitch is that not all ambulances in the area are equipped to transmit ECG data. Realizing the potential for saving lives, Emory has offered in-kind equipment and training to local ambulance systems so they would be able to transmit such data. Some of these endeavors have met with obstacles ("It's unfortunate that politics sometime get in the way of good patient care," says Newman). But Emory is continuing the effort to standardize cardiac care in the region, according to emergency medicine physician Bryan McNally, much the same way that such care already is standardized in the Boston metro area.

Head of the class

Leading the way as standard bearer and creating paradigm shifts to improve care for patients is the academic physician's duty, after all. And so is teaching these standards to as many as possible, helping create, in effect, Emory's own best competition in heart care.

Vassiliades, for example, didn't leave his private practice and join the Emory faculty so he could keep his surgical innovations to himself to make more money. Like Gruentzig before him, he is sharing his knowledge. Since arriving at Emory, he has trained scores of other surgeons to perform endo-ACAB.

And so it goes with others as well. During the past five years, pioneering cardiothoracic surgeon John Puskas has trained surgeons how to perform off-pump bypass surgery. And since the days when Gruentzig was at Emory, cardiologists have been coming here every year to courses on state-of-the-art coronary and peripheral interventions. These courses are broadcast live on the Internet to physicians all over the world.

In fact, Emory has served as a seeding ground, training 85% of the practicing cardiologists and heart surgeons in the state. Puskas, Vassiliades, and Angel Leon, chief of the cardiology service at the Carlyle Fraser Heart Center at ECLH, all received significant portions of their training at Emory. For more than three decades, Emory residencies and fellowships in cardiology and cardiothoracic surgery have been among the most sought after in the nation.

David Harrison, director of cardiology, says Emory offers medical students, residents, and fellows a truly unique learning experience. "Each of the four hospitals where we teach has different patient populations and different strengths," he says. "Our students have patient care experiences that are enormously diverse, much more so than if they trained in only one hospital."

At EUH, students experience either the Logue or Hurst cardiology services, named after cardiologists R. Bruce Logue and J. Willis Hurst, two of the founding fathers of cardiology at The Emory Clinic. When serving on these inpatient cardiology units of EUH, attending physicians must clear their calendars of all other responsibilities and focus only on the patients and medical residents.

"These residents work side by side, for hours on end, with Emory faculty who are world experts in cardiology," says Harrison. "It's patient-based learning. If we have a patient with heart failure, we'll spend a lot of time talking about the pathophysiology of heart failure, how to make the diagnosis, what kind of tests are helpful or not. They get firsthand exposure to some outstanding physicians who have been in cardiology care a long time."

And international experts in cardiology are not hard to find at Emory-owned or affiliated hospitals. Nanette Wenger, director of cardiology at Grady Memorial Hospital, is an expert on heart disease in women. Angel Leon is a leader in using high-tech cardiac resynchronization therapy. And Emory faculty members David DeLurgio, Jonathan Langberg, and Fernando Mera have been instrumental in the advancement of cardiac electrophysiology.

Grady Hospital and the Atlanta Veterans Affairs Medical Center are not technically part of the Emory Heart Center but are staffed by Emory faculty. The experiences cardiology residents and fellows have at these facilities are different, with different patient populations, and equally important.

"Residents and fellows who have spent time in all four of these facilities have had the opportunity to learn how to make their own decisions," says Harrison. "They get much more than just a head full of knowledge. Without these experiences, they would be paralyzed when they got out into the real world."

Back to basics

The value of decision-making ability notwithstanding, a "head full of knowledge" is a good thing too. Basic scientific questions being asked by Emory researchers will yield the treatments of tomorrow. Scientists know that many risk factors - such as high cholesterol, hypertension, obesity, smoking, and lack of exercise - play important roles in the development of heart disease. But what happens inside blood vessels on a cellular level as plaque builds up? What unseen, unnoticed cellular and genetic processes set off the devastating process of atherosclerosis?

Oxidative stress is an important part of the equation, research at Emory has shown. In fact, Emory has become an international center of research into this basic science aspect of heart disease.

Harrison and cardiologist William Weintraub believe markers of oxidative stress and inflammation could hold the key to understanding the early vascular changes linked to atherosclerosis. They are principal investigators in the Markers of Oxidative Stress (MOST) study. Oxidative stress occurs when blood vessels make too many free radicals, overcoming natural protective factors. During normal metabolism, cells produce small amounts of metabolites of oxygen, called reactive oxygen species, which are potentially toxic and can injure cells, including those in the artery walls. Oxidative stress is a condition in which the production of these reactive oxygen species exceeds the ability of cells to remove them.

"Oxidation leads to depletion of important nutrients in our blood vessels, leading to atherosclerotic plaque formation," says Harrison. "Oxidation reactions cause blood levels of certain substances to be elevated. The MOST study will help us identify how those substances correlate with atherosclerosis that hasn't yet shown up clinically."

This strategy could help fight heart attacks before they happen. Harrison and Weintraub are studying blood levels of glutathione, antibodies against oxidized LDL, cholesterol, homocysteine, and C-reactive protein. Results so far suggest that levels of these markers could indicate that oxidative stress and inflammation are occurring.

This information will be correlated along with information on study participants' activity levels, diets, stress levels, and body fat percentage. Then the data will be compared with ultrasound measurements of the volunteers' carotid and brachial arteries, which will show signs of thickening if early atherosclerotic plaque is present.

"The MOST study can help us understand the basic causes of atherosclerosis and could eventually allow us to start treatment before disease is clinically evident," Harrison says.

In another landmark study involving oxidative stress, Emory scientists discovered a new family of enzymes that appears to play a powerful role in oxidative stress, generating abnormal cell growth that occurs in both cancer and some cardiovascular disease. Results were reported recently in Nature.

Through their experiments with NOX1, one of the enzymes in the new class, the scientists, led by biochemist David Lambeth and cardiology researcher Kathy Griendling, found that the reactive oxygen produced by the enzymes functions as a potent growth signal inside cells, instructing cells to divide more rapidly. This can lead to abnormal cell growth causing buildup of atherosclerotic plaque and thickening of blood vessel walls, leading to high blood pressure. Although scientists know that different molecular signals instruct cells to behave in various ways, the cellular mechanisms regulating cell growth have been poorly understood in the past.

The research also demonstrated that the abnormal cell growth directed by these enzymes can be reversed by treatments that remove reactive oxygen from cells. This suggests that drugs designed to block these enzymes or other treatments that destroy reactive oxygen might reverse the process of atherosclerosis or reduce high blood pressure.

Seat of the soul

What all these people - clinicians, basic science researchers, and teachers - have in common is each other. They are willing to work with and rely on each other to take scientific and clinical advances in the treatment of cardiovascular disease to new frontiers. Indeed, these people are the soul of the heart center.

The men and women of the Emory Heart Center are not so different from the construction workers in Doug Morris' photo.

"They have absolutely no fear of height," he marvels. "I don't even see how they could stand up and walk down the beam and get back to work. But they do it every day. The fact is, none of them could accomplish much of anything alone."

Valerie Gregg is a freelance writer.

For more about the Emory Heart Center, visit www.emoryhealthcare.org/departments/heart/.

"Our heart rhythm management center is one of the busiest in the country," he says. "We're also one of the most active clinical research centers in electrophysiology anywhere. We've enrolled more patients in heart resynchronization trials than anywhere else in the country."

"Our heart rhythm management center is one of the busiest in the country," he says. "We're also one of the most active clinical research centers in electrophysiology anywhere. We've enrolled more patients in heart resynchronization trials than anywhere else in the country."

Researchers have long noted an association between depression and cardiovascular disease, but the mechanisms are unclear. A physician with a PhD in epidemiology, Vaccarino has found in recent studies that depression promotes inflammation and oxidative stress. Because these same factors contribute to atherosclerotic plaque formation, they could link depression and heart disease. This means that depression may actually cause heart disease. Another theory is that people with cardiovascular disease could simply be more depressed than their healthier counterparts. Some scientists also argue that depression and heart disease may share common indicators of severe underlying disease. Finding what chemically links the two is Vaccarino's objective.

Researchers have long noted an association between depression and cardiovascular disease, but the mechanisms are unclear. A physician with a PhD in epidemiology, Vaccarino has found in recent studies that depression promotes inflammation and oxidative stress. Because these same factors contribute to atherosclerotic plaque formation, they could link depression and heart disease. This means that depression may actually cause heart disease. Another theory is that people with cardiovascular disease could simply be more depressed than their healthier counterparts. Some scientists also argue that depression and heart disease may share common indicators of severe underlying disease. Finding what chemically links the two is Vaccarino's objective.

In cardiac catheterization, a thin plastic tube is inserted in the femoral artery or vein in the thigh and threaded through the body to repair heart problems. It is best known for its use in angioplasty, which clears blockages that cause heart attacks.

In cardiac catheterization, a thin plastic tube is inserted in the femoral artery or vein in the thigh and threaded through the body to repair heart problems. It is best known for its use in angioplasty, which clears blockages that cause heart attacks.

"By 1960, it was clear that textbooks in cardiology needed redoing," says Hurst. "When individuals were writing them, they took too long to finish. The first chapter was out of date by the time that the last chapter was done. So I came up with the notion of a multi-authored book." That first edition was co-edited by Hurst and cardiologist Bruce Logue. The book is now called Hurst's The Heart.

"By 1960, it was clear that textbooks in cardiology needed redoing," says Hurst. "When individuals were writing them, they took too long to finish. The first chapter was out of date by the time that the last chapter was done. So I came up with the notion of a multi-authored book." That first edition was co-edited by Hurst and cardiologist Bruce Logue. The book is now called Hurst's The Heart.

In 1997, Emory cardiothoracic surgeon John Puskas was already thinking out of the box. The heart-lung machine seemed to be the cause of significant morbidity and occasional mortality during bypass surgery. Using newly developed instruments, he performed the world's first triple bypass surgery on a beating heart, without hooking the patient up to a heart-lung machine. It was a huge success. Although only 20% of surgeons in the United States now use this "off-pump" technique, it is standard procedure today at Emory Hospital.

In 1997, Emory cardiothoracic surgeon John Puskas was already thinking out of the box. The heart-lung machine seemed to be the cause of significant morbidity and occasional mortality during bypass surgery. Using newly developed instruments, he performed the world's first triple bypass surgery on a beating heart, without hooking the patient up to a heart-lung machine. It was a huge success. Although only 20% of surgeons in the United States now use this "off-pump" technique, it is standard procedure today at Emory Hospital.