Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta has designated $430 million from its endowment to create a pediatric research powerhouse involving Emory, Georgia Tech, and other research and academic institutions

in Georgia.

Over time, the investment will change the pediatric research landscape, especially in areas such as heart disease, oncology, and neuroscience. Additionally, the partnership will attract top medical talent and grants as well as prime the pump for start-up companies to help develop new treatments and vaccines.

The initiative opens the door to further collaboration between Emory and Children’s. Since 2004, pediatric researchers, clinicians, and teachers have lived under one roof in the building that houses the Emory-Children’s Center (ECC) on the Egleston campus. In 2006, Emory and Children’s agreed to operate ECC jointly as the largest pediatric multispecialty group practice in Georgia.

Emory has ramped up an earlier plan to expand its patient care and research facilities.

This summer, the Board of Trustees approved a $73 million proposal that includes replacing Emory University Hospital with a new hospital. Two years ago, Emory announced plans to construct a new Emory Clinic complex, along with a replacement for Emory Hospital, to be located and built in phases across Clifton Road from the hospital’s current site. The new proposal calls for expanding facilities at Emory Crawford Long Hospital in Midtown, which was not part of the 2006 plan.

New Clifton Road facilities now include a 250-bed hospital, replacing 100 beds currently in Emory Hospital for a net gain of 150 beds; a new 395,000-square-foot Emory Clinic to be built next to the current clinic; a larger emergency department in the new hospital; and a new 100,000-square-foot research building across from the Emory-Children’s Center.

Expansion of the Midtown campus includes the addition of 125 new hospital beds, a 137,000-square-foot Emory Clinic building, and 75,000 square feet of new research space.

The new proposal is founded on several years of planning guided by community input to create a more integrated approach to health care that can respond nimbly to patient demand.

Scientists at Yerkes National Primate Research Center and the Department of Human Genetics have developed the first transgenic nonhuman primate model of Huntington’s disease (HD).

Until now, researchers used transgenic mice to study HD, but the models did not completely parallel the brain changes and behavioral features that characterize people with the inherited disorder. Patients experience uncontrolled movements, loss of mental processing capabilities, and emotional disturbances.

“The transgenic monkeys provide us with unparalleled opportunities for assessments that mirror the ones used with humans,” says lead researcher Anthony Chan. “With such information, much of which we are obtaining by using Yerkes’ imaging capabilities, we are developing a more comprehensive view of the disease.”

The researchers believe their progress bodes well for developing transgenic monkey models of other neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. In the case of HD, such models may bring hope to the five to 10 people in every 100,000 who are affected. Patients succumb to the disease within 10 to 15 years of symptom onset.

| ny | tiny font | ny |

| Medical and nursing students practice teamwork in the experiential learning center. | ||

The patient winced with pain. A steel construction beam fell on his leg, and now he was in the hospital, asking the attentive medical team for a strong painkiller. He wanted morphine, and the team decided that prescribing the drug was the right course of action.

If the patient had landed in a typical emergency room with stretched resources, he might not have had so many people attending to him. This patient was a mannequin in the experiential learning center, with third-year medical students and senior nursing students in attendance.

It also was the first time in Emory history that both medical and nursing students trained together. Students were briefed on basic teamwork and skills and then ran through one of two scenarios: a 52-year-old construction worker with a leg injury or the same patient who later develops chest pain. Afterward, students talked about what worked and what didn’t with medical and nursing faculty who served as facilitators.

One point the students learned: Don’t talk over the patient. Designate a team member to be the “explainer,” an increasingly important role as health care gravitates toward allowing family members to stay in the patient’s room.

One nursing student liked how her team established a first-name basis with each other to put everyone on equal footing. “I liked it too,” added a medical student. “I didn’t walk into the room and think, ‘I’m the doctor and that’s the nurse.’ ”

While all of the students learned valuable lessons that day, few medical and nursing schools incorporate team training into their curricula. And they’re missing a golden opportunity to improve patient care, says Douglas Ander, director of the Emory Center for Experiential Learning and an emergency medicine physician.

“When health care teams are properly trained on how to work together, the result is better teamwork, reduced medical mistakes, and improved patient care,” says Ander. “The more time students train together at an earlier stage, the more it will be ingrained in their normal mode of operation. Typically, students and residents have little to no understanding of how teams function in a real health care environment.”—Kay Torrance

TLC for damaged hips and shoulders

Used to be that total hip replacement was the best option for patients with arthritis of the hip. A new surgical procedure introduced recently to the United States offers a less drastic alternative for young, active patients with significant hip degeneration.

Known as hip resurfacing, the surgery preserves more of the hip’s natural bone structure and provides a larger head ball, contributing to a more stable hip joint and potentially increased range of motion.

Recovery is similar to total hip replacement, with most patients up and walking within 24 hours of surgery with physical therapy, followed by a progressive increase in activity. “Most patients find that resuming a more normal, pain-free lifestyle occurs rapidly,” says Emory orthopaedic surgeon Greg Erens.

He cautions that the procedure isn’t for everyone. People with brittle bones, severe deformity of the hip, or dead bone or who are significantly overweight are not good candidates. In those cases, total hip replacement may be the best option.

Another new technique is helping patients with rotator cuff injuries. The “double-row” arthroscopic repair allows the tendons around the shoulder joint to heal more dependably and lowers the risk of reinjury by securing the tendon to the bone at two sites rather than one.

“It is much stronger than a typical ‘single-row’ repair and does a better job of restoring normal rotator cuff anatomy,” says Speros Karas of the Emory Sports Medicine Center. “Recent studies also show that the ‘double-row’ repair heals in a more stable fashion, which results in better long-term outcomes.”

| ny | tiny font | ny |

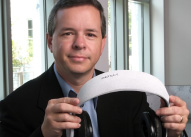

| David Wright (above) and Michelle LaPlaca developed DETECT to screen patients for early-stage Alzheimer’s. | ||

By 2040, some 81 million people worldwide are expected to have Alzheimer’s disease. School of Medicine scientists want to make sure that doesn’t happen.

Neurologist Allan Levey is leading the first clinical trial of a new vaccine designed to slow Alzheimer’s progression. The vaccine targets the beta-amyloid protein that forms plaque and eventually damages brain cells.

Previous research on genetically engineered mice found that vaccination with beta-amyloid at birth protects them from plaque formation and mental decline; older mice also showed some benefit from the vaccine.

The Merck vaccine that Levey is testing uses a smaller piece of beta-amyloid protein to stimulate antibody production but avoid stimulating T cells, the shock troops in an inflammatory response. Levey’s four-year study will evaluate vaccine safety, possible side effects, and how well the vaccine stimulates the immune system in men and women age 55 and older.

Another Emory physician helped devise a tool to diagnose early-stage Alzheimer’s. Called DETECT, the helmet device includes an LCD display in a visor, along with a computer and noise-reduction headphones. DETECT gives the patient a battery of words and pictures to assess cognitive abilities—reaction time and memory capabilities. The low-cost test takes approximately 10 minutes.

“With this device, we might be able to pick up impairment well before serious symptoms occur and start patients on medications that could delay those symptoms,” says emergency medicine physician David Wright, who co-developed DETECT with Michelle LaPlaca, a scientist in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech and Emory.

DETECT’s creators formed the company Zenda Technologies to commercialize the device, expected to be available later this year. They hope the device will become part of a regular medical exam, much like a PSA test or ECG given by general practitioners.

| ny | tiny font | ny |

Scientists from Emory and New Delhi will soon begin pre-clinical trials of an HIV vaccine in India, marking the first scientific collaboration of the International Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (ICGEB) and the Emory Vaccine Center, based in the School of Medicine.

The vaccine is a promising candidate, says Rafi Ahmed, director of the Emory Vaccine Center. It is an off-shoot of the HIV vaccine developed by Yerkes National Primate Research Center microbiologists Harriet Robinson (who now serves with GeoVax, the Emory startup company that developed the vaccine) and Rama Amara that will soon enter phase 2 trials in the United States. The vaccine, Amara believes, can be tailored to fit the dominant strain of HIV in India, where the largest number of HIV-infected people in the world live. He and ICGEB immunologist Shahib Jameel will shepherd the Indian vaccine.

While the vaccine trial is the center’s first, more partnerships are in store after Emory hires three faculty members by the end of 2008 to be stationed in New Delhi. At least one of the new hires will specialize in tuberculosis to fulfill a center mandate to develop a research program in tuberculosis.

The ICGEB-Emory Vaccine Center was launched this year to develop vaccines for some of the world’s most prevalent and deadly infectious diseases, particularly in underserved nations. HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis are two top interests, along with hepatitis C, dengue fever, and malaria.

Founded by the United Nations, the ICGEB has facilities in India, Italy, and South Africa and focuses on research and training in molecular biology and biotechnology. In addition to allowing Emory and ICGEB researchers to work side-by-side, conducting research in India brings access to patient populations, biological materials, and Indian epidemiological data not readily available in the United States.—Kay Torrance

Ophthalmologists treating patients with age-related macular degeneration (AMD) often face a dilemma. Is it better to treat their patients with Lucentis or Avastin? Manufactured by Genentech, both drugs are chemically similar and inhibit the vascular endothelial growth factor that stimulates abnormal blood vessel growth under the macula, causing “wet” AMD.

Yet there are major differences. The FDA approved Lucentis (ranibizumab) for ophthalmic use in 2006. Before then, physicians prescribed Avastin (bevacizumab) off label and continue to do so. Lucentis costs $2,000 per dose, while Avastin is about $50 per dose.

A two-year nationwide study led by the Emory Eye Center is comparing the drugs’ benefits head to head. Funded by the National Eye Institute, the Comparison of Age-Related Macular Degeneration Treatment Trials (CATT) will involve 1,200 patients newly diagnosed with “wet” AMD.

The FDA approved Lucentis based on clinical trial results showing that the drug slows the rate of progressive vision loss from advanced AMD. Approximately one-third of patients treated in these trials showed improved vision at 12 months. Although not approved by the FDA for ophthalmic use, Avastin is approved for treating colorectal cancer and also is used for lung cancer.

“Since these are the two primary drugs for treatment of this disease, it is important for the visual health of the public to understand if there is any difference between them,” says retina specialist and study leader Daniel Martin.

“This study has huge socio-economic implications, not only for ophthalmic care but health care in general,” adds Timothy Olsen, chair of the Department of Ophthalmology. “Newer biologics may also be studied in a similar manner, and the CATT study will set the stage for future comparisons.”

| ny | tiny font | ny |

| David DeLurgio uses Sensei to destroy cells that cause heart arrhythmias. | ||

New options for heart patients

Physicians at Emory University Hospital are the first in the Southeast to use percutaneous aortic valve replacement, a nonsurgical experimental option for patients with aortic stenosis.

In this new procedure, doctors create a small incision in the groin or chest wall and then feed a wire mesh valve through a catheter and place it where the new valve is needed. French cardiologist Alain Cribier performed the first percutaneous heart valve replacement in 2002. Interventional cardiologist Vasilis Babaliaros learned alongside Cribier and brought the procedure to the United States and Emory. Babaliaros and cardiologist Peter Block are leading a clinical trial at Emory, one of five sites nationwide.

“This procedure is much easier on the patient, and it offers a quicker recovery time,” says Babaliaros. “Most important, it may also extend the lives of many people who are too ill or too frail to endure open-heart surgery.”

Patients with heart arrhythmias also have a new treatment option at Emory Crawford Long Hospital (ECLH). The hospital is the first in the Southeast to offer a robotic catheter ablation system known as Sensei.

Using live x-ray, the physician guides the robotic catheter with an electrode at its tip into the heart and places the tip at the exact site where cells are giving off electrical signals that stimulate the abnormal heart rhythm. Mild and painless radio-frequency energy is transmitted to the targeted area, destroying the heart muscle cells in a small area (about 1/5 inch). The treatment stops the area from conducting the extra impulses that cause the rapid heartbeats.

Sensei provides advantages for both patient and doctor, says David DeLurgio, who directs the electrophysiology labs at ECLH. It improves accuracy and control over the tip of the robotic catheter. And because Sensei is operated remotely, physicians are exposed less to radiation and experience less fatigue, since they sit rather than stand during the procedure.

| ny | tiny font | ny |

| Josh Ziperstein, 11M (right), mentors Atlanta High School students through the Pipeline Program, founded by two Emory medical students. | ||

Working through a case study about sickened churchgoers following a picnic, the high-schoolers diligently figured out the responsible party: Staphylococcus aureus endotoxin. Exclaimed one sophomore: “I didn’t know I was so smart.”

It was just the kind of sentiment that his mentors hoped to hear, given that many students at South Atlanta High School perform poorly academically. In fact, 90% of them live in poverty. Attendance is far from daily for many, who often do not go on to college. The students were a good fit for the Pipeline Program, created by two Emory medical students.

Samuel Funt and Zwade Marshall started the program to improve academics and foster interest in the sciences among at-risk high school students. They modeled the program after one that Funt participated in as a University of Pennsylvania undergraduate.

“After three months of first-year classes at Emory, it became clear that I had many years to go before I would be able to really help people in a clinical setting,” says Funt, now a third-year medical student. “Zwade and I created the Pipeline Program because we didn’t want to wait to become master diagnosticians to begin improving the health of our community.”

With the help of Robert Lee, associate dean for multicultural medical student affairs, Funt and Marshall contacted the Atlanta public school system and got the go-ahead to launch the program at South Atlanta School of Health and Medical Sciences, a division of South Atlanta High School. Then they recruited other medical students and undergraduates from Emory to guide the students.

In the first two sessions, the high school students came to the School of Medicine to get a taste of advanced medical concepts and terminology. Then Funt, Marshall, and other mentors visited the high school to work on case studies related to food poisoning and HIV. Students looked up epidemiologic terms, sorted data on Excel, and calculated incubation times. The mentors also talked about colleges and careers.

By early spring, attendance by the 26 students was up 26%, and 86.6% of students had passed their courses, says principal Termerion McCrary. (Last fall, 39% failed at least one course.) Several Pipeline students also expressed interest in a health career.

Funt wants the students to have the same supportive relationships that he had. “Because the population at South Atlanta High is affected by generational poverty, many of the students are not able to develop these ties and therefore come to school with limited expectations for success,” he says. “The Pipeline Program is designed to foster meaningful relationships that will give these young people the confidence and motivation to continue on to college and develop healthy attitudes and practices.”—Kay Torrance

That’s Luella Klein, who led the Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics from 1986 to 1992. Today, four women chair departments: Sarah Berga (gynecology and obstetrics since 2003), Katherine Heilpern (emergency medicine since 2007), Carolyn Meltzer (radiology since 2007), and Barbara Stoll (pediatrics since 2004).

This issue of Emory Medicine happens to feature another prominent woman in School of Medicine history. For more about her, see the story on Love Affair with the Heart. Hint: She joined the Department of Medicine 50 years ago. . .

Back to Top | SOM home

© 2008. Emory University, All rights reserved.