Remembering a health pioneer

For David Sencer, the well-being of others always came first

Former CDC director David Sencer used to rely on the point system to recruit students for Emory’s master of community health program. He would point to a CDC staff member and say, “You are going.”

Sencer, a founding father of the Rollins School of Public Health, died from complications of heart disease on May 2 at age 86.

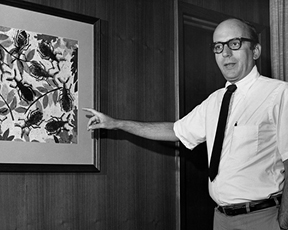

(Top) The family of David Sencer provided support to create a scholarship named in his honor. They include son David, daughter Susan, wife Jane, and daughter Ann. (Bottom) Sencer, shown here in his office at the CDC, led the agency from 1966 to 1977. He is pointing to a piece of artwork depicting the “kissing bugs” known to transmit Chagas disease. |

As the longest-serving director of the CDC, Sencer oversaw a substantial expansion of the agency as it dealt for the first time with malaria, nutrition, health education, and occupational safety. Its greatest success during his tenure was a program that eradicated smallpox, beginning in central Africa and eventually extending worldwide.

Sencer also was instrumental in partnering with Emory faculty to establish a master of community health program in 1974. By the 1990s, the program had evolved into the Rollins School of Public Health. Along with his leadership during the smallpox eradication campaign, he counted the program and school among his greatest contributions to public health.

When Sencer became CDC director, the agency was small enough for him to know almost everyone by name. “David didn’t supervise as much as he enabled. He prowled the building to find out what was going on,” said William Foege, Emeritus Presidential Distinguished Professor of International Health. Foege, who worked on smallpox eradication in Africa, succeeded Sencer as CDC director.

As many attest, Sencer cared deeply about the health of populations, the well-being of staff, and educating future public leaders. “We all would have walked through fire for him,” said Foege, who spoke during a June memorial service at Rollins.

Two incidents shaped Sencer’s worldview and career path. In his 20s, he contracted tuberculosis, which required a long recovery. He later joined the U.S. Public Health Service, and one of his first assignments took to him Idaho, where he conducted a health survey of migrant laborers.

“It was then that I first began to see the rewards of dealing with groups of people rather than individual patients,” Sencer told Emory students with REACH (Recognizing & Encouraging Aspirations in Community Health), which honored him with its first lifetime achievement award a few years ago.

For three years, Sencer led a community-based research program in tuberculosis control in Muscogee County, Georgia. In 1960, he transferred to Atlanta to serve as assistant director of the CDC—then known as the Communicable Disease Center. He was appointed director of the CDC in 1966.

Courage under fire

James Curran and Sencer, shown here in 2008. |

Under his leadership, the agency expanded dramatically by entering the global arena, adding domestic programs, and assuming responsibility for vaccination programs against polio and childhood diseases and for surveillance and control of tuberculosis and sexually transmitted diseases. He helped focus efforts in chronic disease prevention and control—beginning with a national education campaign about the dangers of smoking. Sencer heeded his agency’s advice and quit smoking.

RSPH Dean James Curran first met Sencer in 1974 at Harvard, where the CDC director was a visiting fellow.

“Dr. Sencer was the epitome of public health,” said Curran during the memorial service. “He was fearless in its mission. It was never about him. It was about the people.”

Of all the challenges that Sencer faced at the CDC, the 1976 swine flu outbreak proved to be the most difficult. Concerned about a possible pandemic, Sencer’s team recommended that all Americans be immunized. In two months, 43 million people were vaccinated. But when more than 25 of them died of Guillain-Barré syndrome, the vaccination program was halted. In 1977, Sencer was dismissed by Washington officials.

“He made the right call, even though the swine flu virus did not cause a pandemic,” said Foege. “He showed courage in doing what needed to be done to protect the public.”

Later, as health commissioner of New York City from 1982 to 1986, Sencer faced public and political pressure again during the early years of the AIDs epidemic. He established surveillance parameters and recommended the course of the city’s response to AIDs. He also convinced Mayor Ed Koch to start a clean needle program to prevent AIDs transmission among drug addicts.

Thomas Frieden served as New York City health commissioner before joining the CDC as director in 2009.

“One of the wonderful things about coming to the CDC was getting to know David Sencer,” said Frieden during the memorial service. “He was my compass for where we needed to go in public health.”

After leaving New York, Sencer served as an international public health consultant before retiring to Atlanta with his wife Jane. Not one to sit still, he taught public health and medical students at Emory and developed an archive on global disease eradication, assisted by the RSPH, Emory’s Woodruff Library and Global Health Institute, and the CDC. Launched in 2009, the Global Health Chronicles is an online resource on the eradication of smallpox and Guinea worm disease.

In 2008, the RSPH established the David J. Sencer MD, MPH, Scholarship Fund with support from his family. Scholarship recipients must be state and local public health professionals who exemplify leadership and service in the field—the same characteristics that Sencer demonstrated throughout his career.

Following his death, the federal agency he led renamed the David J. Sencer CDC Museum in his honor.

When Sencer first learned about the scholarship named for him, he summed up his career in his typical low-key fashion: “When you do good work, it’s fun.”

Surviving him are his wife Jane, a son, two daughters, and six grandchildren. Stephen Sencer serves as general counsel of Emory. Susan Sencer-Mura is a pediatric oncologist in Minneapolis, and Ann Sencer is an oncology nurse practitioner at Emory University Hospital Midtown.—Pam Auchmutey

|

To make a memorial gift to the David J. Sencer MD, MPH, Scholarship Fund, please visit sph.emory.edu/alumni_gift. |

||||