A no-crack solution to aortic stenosis

Vinod Thourani, Vasilis Babaliaros, Robert Guyton, and Peter Block

A new alternative to open heart surgery brings together the disparate camps of interventional cardiologists and heart surgeons

By Martha Nolan McKenzie

Izie Lang went to see his cardiologist when his shortness of breath got so bad that he couldn’t walk from his house to his car without getting winded. The doctor diagnosed Lang with severe aortic stenosis—a narrowing of the aortic valve that results in restricted blood flow and immense strain on the heart.

But at 93, Lang was deemed too old to undergo the surgery traditionally used to replace diseased valves.

So Lang’s Jacksonville, Fla., cardiologist referred him to the Emory Heart & Vascular Center. There, a team of cardiologists and cardiac surgeons replaced his diseased valve with a new one via a nonsurgical procedure that snaked the new valve through an artery in his groin and up into place in his heart.

That was a little over a year ago. Today Lang is back to his old self—driving, socializing with friends at the local senior center, and going ballroom dancing at least three times a week. “I’ve got to say, I feel pretty good,” says Lang.

Lang was part of a study that holds promise for patients with aortic stenosis who are too old or too sick to undergo surgery. Dubbed PARTNER, the FDA clinical trial measured a new nonsurgical procedure, transcatheter aortic valve replacement, or TAVR—against traditional open heart surgery. Emory University Hospital was one of 22 sites nationwide—and the only one in Georgia—in the PARTNER I study. PARTNER I is winding down, and patients now are being enrolled in PARTNER II.

Snaking a new valve

“Aortic stenosis is progressive and relentless,” says Vasilis Babaliaros, an interventional cardiologist and a co-principal investigator for PARTNER II. “Once you develop symptoms, you are dead within six months to three years without surgery. In the past, the only alternatives for these patients were hospice and palliative care.” About 20% to 30% of those who suffer from aortic stenosis are considered ineligible as candidates for surgery.

|

|

|

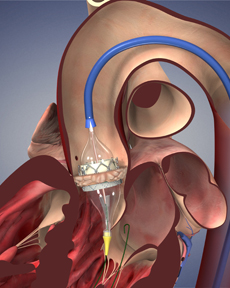

The valve is pushed up into position in the heart, and when it is in place, a balloon inflates the stent, pushing the old valve out of the way. |

TAVR offers another alternative. With TAVR, patients do not have to have their chest opened or their heart stopped and go on a cardiopulmonary bypass machine, as is required with a surgical valve replacement. Instead, the new valve is delivered via a catheter in one of two ways. If the arteries in the patient’s groin are large enough, a catheter bearing a new bovine valve inside a collapsed metal mesh stent is inserted through the groin artery. It is pushed up into position in the heart, and when it is in place, a balloon inflates the stent, pushing the old valve out of the way. The balloon and catheter are removed, and the new valve takes over. If the artery in the groin is too small to accept a catheter, physicians make a small incision in the chest, over the tip of the heart, and feed the catheter through the heart into position. This procedure is more invasive than the groin option but still much less so than standard surgery.

The outcomes from both types of procedures are promising. In the PARTNER I trial, all nonoperative candidates received the TAVR procedure. Another group of patients considered at high risk were randomized between a traditional surgical valve replacement and TAVR. In the nonoperative group, mortality at one year fell from 50% to 30%. For high-risk operative patients, the one-year mortality rate with TAVR was roughly equal to the rate with traditional surgery, about 70%.

“These are good outcomes, especially when you consider how sick the patients are,” says Peter Block, interventional cardiologist and a co-principal investigator for PARTNER I. “In fact, most of the deaths at one year were not from aortic stenosis but from their associated conditions that made them inoperable or high risk in the first place. Their valves seem to be working just fine, but they are dying of cancers, lung disease, or coronary artery disease.”

To get an idea of outcomes related strictly to the procedure, Babaliaros points to mortality at 30 days post-procedure. “Thirty days is a very special endpoint in surgical literature,” he says. “Everything that happens to the patient from the day of surgery to 30 days out you blame on the procedure. The 30-day mortality of implanting the valve through the leg was half of that of traditional surgery for high-risk patients.”

TAVR vs. the standard

Physicians caution that these results don’t mean everyone should opt for TAVR over traditional valve replacement. “The standard surgical valve replacement is a known entity,” says Robert Guyton, chief of cardiothoracic surgery at Emory Healthcare and a principal investigator for PARTNER I. “We’ve had experience with the surgery going back to the 1960s. We know how long the valve lasts. On the other hand, TAVR has just been around for about seven years, and we don’t know how long the valves last. And the study showed a stroke rate about twice as high with TAVR as with standard surgery.”

That stroke risk is still small, less than 10%, making TAVR an alternative for high-risk patients. “This is a major breakthrough in the treatment of patients who are considered nonoperative,” says Vinod Thourani, a cardiac surgeon and a principal investigator for PARTNER II. “It allows us for the first time to offer an option to patients who in the past had no options.”

The initial TAVR study results are so promising, in fact, that the FDA green-lighted the valve in early November. The valve is expected to revolutionize the treatment of severe aortic stenosis, says Thourani, who also sits on the national PARTNER II steering and publication committees.

Success also spawned the second phase, PARTNER II. This trial will look at the use of a smaller device as well as test the procedure in healthier patients—those who pose a moderate surgical risk. The latter may help researchers determine how long these new valves can be expected to last.

“We don’t know how long the transcatheter valves last because most patients who get them don’t live that long due to their other conditions,” says Babaliaros. “The longest survivor that we know of is a Parisian woman who has had the valve about eight years. But when we start implanting these valves into moderate-risk patients, they could well live longer, allowing us to track the valves over more years.”

Dissolving fixed borders

Emory physicians laid the groundwork for the TAVR procedure years ago, arguably going back several decades. Block began investigating structural heart and valve disease in the early 1980s and was the first physician in the United States to dilate the mitral valve. He also had a connection with the French physician Alain Cribier, who pioneered the TAVR procedure in 2002, and he was able to arrange for Babaliaros, then a fellow under Block, to go to France for a year to work with Cribier.

“Not only was I involved in the implants—we did patients No. 17 to No. 40 the year I was there—but we spent so much time writing together that I got to walk around in the mind of the pioneer,” says Babaliaros, now an interventional cardiologist. “I got to understand the spirit of the procedure, the goals, the limitations, and the future of the device.”

After Babaliaros returned to Emory in late 2005, he and Block decided to set up a structural heart disease program and to try to land a place in the new PARTNER trial.

“The procedure kept evolving—one way the procedure is done more interventional cardiology, the other way is more surgical so we put a team together of cardiologists and surgeons that would understand both aspects,” Babaliaros says.

They were joined by cardiac surgeons Guyton and Thourani, along with one research coordinator and one fellow. “Even with that small team, we were not only able to get into the trial, but we were one of the largest enrollers, with close to 200 patients so far, ” says Babaliaros.

Much of that success stems from collaboration between formerly disparate camps. “This is truly a new paradigm,” says Thourani. “The cardiologists are teaching the surgeons catheter skills, and the surgeons are teaching the cardiologists about the surgical management of aortic stenosis.”

Says Babaliaros, “In the past, there have been fixed borders between cardiologists and cardiac surgeons. They use a knife and sutures, we use catheters and small needles. But with TAVR, we have come together—a cardiologist and cardiac surgeon work together for each case. As a result, I think, the whole is much bigger than the sum of the parts.” EM

To watch a video on TAVR, access tinyurl.com/TAVR-patient.