| |

|

| Thomas J. Lawley, Dean |

Research, going forward

As you read in an earlier issue of this newsletter, we are in the process of mapping out our next five-year research strategic plan. We have fleshed out more details, and I want to update you on the plan.

When I was named dean in 1996, our school had $55 million in NIH funding, which placed it 31st in ranking. Since then, we have steadily climbed in rank and funding, guided these many years by our research strategic plans. Through

our research plans and exceptional investigators, we continue to grow at the second fastest rate of the top 20 medical schools, 13.1% annually over the past 13 years, in fact. This year we moved to 15th place with $272 million.

Our previous research strategic plans put in place the key components to reach our current ranking. During the late 1990s, we built critical mass. We ran a number of individual labs at the time and simply needed more investigators to move into team science. By 2003, we had increased our NIH-funded investigators to 263, and more than doubled our NIH funding since 1997. From then on, we really hit our stride.

In 2003, our focus on team science coincided with the vision of the then-director of the NIH, who made funding team science a priority. The results for us were cancer SPORES (specialized projects of research excellence funded by the NIH),

program project grants, and the development or expansion of research centers, such as the Winship Cancer Institute. In particular, we made strong inroads in neuroscience and immunology research.

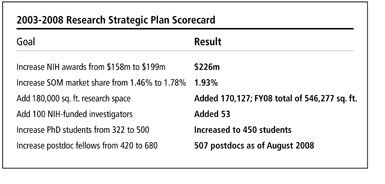

So how did we do? Overall, we accomplished a lot from 2003 to 2008 (see the "scorecard" to the left). Our NIH awards grew faster than we predicted, and this is a substantial accomplishment, considering two factors. The NIH's budget had remained relatively

flat during those years, and we added fewer investigators than planned. We did add almost as much research space as planned. There are three areas in our 2003 plan in which we still have room for improvement: aligning the medical school with the multiple missions of WHSC, enhancing research infrastructure, and increasing support to investigators in clinical departments. So how did we do? Overall, we accomplished a lot from 2003 to 2008 (see the "scorecard" to the left). Our NIH awards grew faster than we predicted, and this is a substantial accomplishment, considering two factors. The NIH's budget had remained relatively

flat during those years, and we added fewer investigators than planned. We did add almost as much research space as planned. There are three areas in our 2003 plan in which we still have room for improvement: aligning the medical school with the multiple missions of WHSC, enhancing research infrastructure, and increasing support to investigators in clinical departments.

Since 1997 our vision has included achieving top 10 NIH ranking. This is a worthwhile goal, but going forward it needs a little fine-tuning. What we should focus on is research that is important, not simply securing grants to secure a rank. We want to make a difference in the health of our nation's citizens and in how we understand disease. We are not putting aside that top 10 goal, but we are going to shift our thinking fundamentally about research over the next five years.

Our philosophy, in a nutshell, will be: If we first enhance mind-share, market share will follow. We have matured enough as a school to focus on actual achievement instead of using research grant awards as a primary measure of success.

With that in mind, we have created a proposed research mission statement, something we have never put on paper before. Our mission is formed around three words, create, advance, and inspire. Create innovative, collaborative discovery programs that advance health by prevention, early detection and treatment, and inspire hope through research. It is

a timeless mission, and how we will strive toward it leads us to our (draft) vision statement: By 2015, Emory University School of Medicine will have had substantial impact on the understanding of human disease and improvement of human health and will be recognized

as one of the top 10 research-intensive medical schools in the country.

Looking forward, our 2009 research strategic plan will rest on three principles: We will use achievements as a primary measure of research success, improve infrastructure, and develop programmatically outside of the school.

Measuring past success

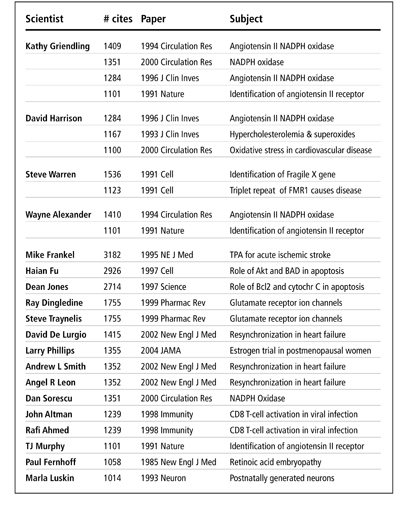

As we move from reliance on financial metrics to identifying specific research achievements, we need more ways to recognize faculty. One of those ways is the Emory University MilliPub Club, whose initial 19 members (see chart, right) were inducted in September. The club recognizes faculty who have published individual papers at Emory that have at least 1,000 citations. As we move from reliance on financial metrics to identifying specific research achievements, we need more ways to recognize faculty. One of those ways is the Emory University MilliPub Club, whose initial 19 members (see chart, right) were inducted in September. The club recognizes faculty who have published individual papers at Emory that have at least 1,000 citations.

A citation count is important because a researcher's impact is judged by the number of times the paper is cited by other researchers. "A paper that is cited more than 1,000 times is equivalent to a pharmaceutical blockbuster," says Ray

Dingledine, Executive Associate Dean for Research and Chair of Pharmacology.

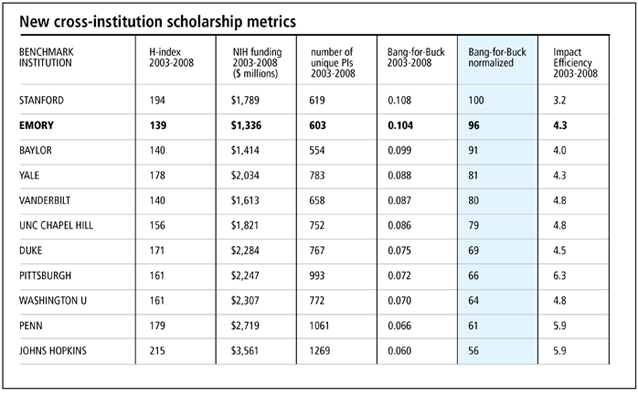

Dingledine has taken the work of Millipub members and many other high impact papers to come up with a new measure of our research impact. He has named it the "Bang-for-Buck" index, based on a well-known citation metric, the H-index. A school's H-index (see table below) is its highest number of research publications with at least an equal number of citations. For example, Emory's H-index of 139 (from 2003-2008) means that Emory faculty published a total of 139 papers with at least 139 citations for each paper. Stanford's H-index of 194 means that its faculty published 194 papers that each have at least 194 citations, and so forth. Of course, a school's H-index is influenced not only by the quality of science but also by the number of investigators it has and how much NIH funding they secure.

The Bang-for-Buck metric divides each school's H-index by the total NIH funding it received for that time period. Bang-for-Buck represents the value added by each million awarded by the NIH. By this metric, Emory ranks second among its peers, topped only by Stanford. "In essence, we make the most of money we receive," says Dingledine. "We produce more high-impact papers per dollar than most other institutions."

The rightmost column in the chart shows Research Impact Efficiency, another new metric formed by dividing a school's number of investigators by its H-index. This metric indicates how many investigators were needed in a given school to generate one additional high-impact paper.

"These measures are new ways for assessing the research impact of institutions that I think may be of interest nationally," says Dingledine. "For medical schools that rank in the 30s or mid-20s in NIH funding, measuring one's progress by the growth in NIH funding is fitting. But once a school moves into the teens, it becomes appropriate to use more direct measures of research impact and contributions."

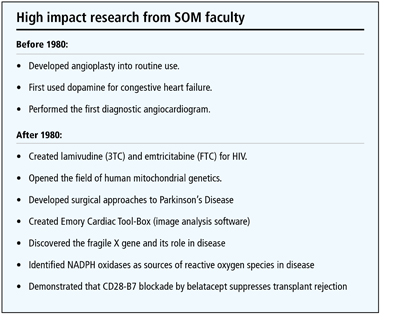

Along these lines, we are beginning to compile a list of high impact research by medical faculty (see list, left). "Each one of these contributions has had worldwide impact," says Dingledine. "For example, the AIDS drugs invented by Raymond Schinazi and Dennis Liotta are taken by more than 80% of HIV patients worldwide. The Emory Cardiac ToolBox, created over a decade by Ernest Garcia and his collaborators, is now used by more than 10,000 hospitals to interpret cardiac scans. Each of these and many more research discoveries or developments have their own story, which we are listing on the school's website." A number of contributions are teed up and nearly ready to join the list: progesterone for traumatic brain injury pioneered by Donald Stein and David Wright, deep brain stimulation for major depression studied by Helen Mayberg, and the discovery of an endogenous factor that controls sleepiness, identified by David Rye, Andrew Jenkins, and their collaborators. Along these lines, we are beginning to compile a list of high impact research by medical faculty (see list, left). "Each one of these contributions has had worldwide impact," says Dingledine. "For example, the AIDS drugs invented by Raymond Schinazi and Dennis Liotta are taken by more than 80% of HIV patients worldwide. The Emory Cardiac ToolBox, created over a decade by Ernest Garcia and his collaborators, is now used by more than 10,000 hospitals to interpret cardiac scans. Each of these and many more research discoveries or developments have their own story, which we are listing on the school's website." A number of contributions are teed up and nearly ready to join the list: progesterone for traumatic brain injury pioneered by Donald Stein and David Wright, deep brain stimulation for major depression studied by Helen Mayberg, and the discovery of an endogenous factor that controls sleepiness, identified by David Rye, Andrew Jenkins, and their collaborators.

The plan, here on out

Dingledine and Radiology Chair Carolyn Meltzer have headed up our planning process, with a multidisciplinary team of 27 faculty to further devise the plan. Committees were formed to look at a number of issues, including one of our biggest challenges, research infrastructure. Like most rapidly growing institutions, we have outstripped our research infrastructure. Despite the largest building boom in Emory's history during the past decade—much of it dedicated to the health sciences—the medical school still has limited research space. Furthermore, our infrastructure support for our researchers has not kept pace with the growth in regulatory burdens. Faculty have noted the increasing amount of time they spend navigating compliance and administrative hurdles. Based on their feedback, we developed six goals for the next five years:

-

Shift focus from exclusive reliance on financial metrics to identification of specific research achievements.

-

Align and integrate our research and clinical activities.

-

Develop research partnerships that strengthen our impact.

-

Improve administrative support for investigators to facilitate grant submission and management.

-

Strengthen research core facilities.

-

Develop additional research space to support programmatic expansion, including emerging centers and team science.

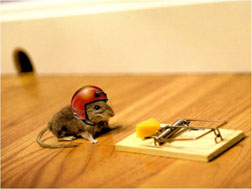

Granted, the economy will be the biggest factor that will affect our plan. For those of you who have seen Dingledine and Meltzer's presentation on the research strategic plan, you'll

recognize the picture to the right. Just like that mouse, we need to bite off the right-sized chunk of goals, to avoid getting clunked in the head. The belt-tightening that we have implemented this past fiscal year will continue until the economy fully recovers.

We will continue to flesh out how we want to distribute our resources for the next few years. Granted, the economy will be the biggest factor that will affect our plan. For those of you who have seen Dingledine and Meltzer's presentation on the research strategic plan, you'll

recognize the picture to the right. Just like that mouse, we need to bite off the right-sized chunk of goals, to avoid getting clunked in the head. The belt-tightening that we have implemented this past fiscal year will continue until the economy fully recovers.

We will continue to flesh out how we want to distribute our resources for the next few years.

|

|