A scar that tells a story

If you’re a teenager with a bad heart, it can be hard to talk about the scar running from your neck all the way down to your stomach or the cadaver valve in your chest. It can be difficult to explain the challenges of living with a rare congenital heart condition that has necessitated multiple surgeries.

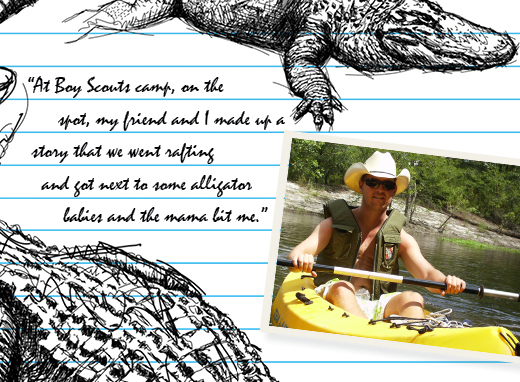

So as a teenager a decade ago, Emory heart patient Andrew Sawyer got creative. “At Boy Scouts camp, on the spot, my friend and I made up a story that we went rafting and got next to some alligator babies and the mama bit me. So I had to have a little surgery to realign this whole thing.” For the rest of the week, fellow campers ran up to Sawyer, exclaiming, “You’re the guy that got attacked by the alligator!”

Now the teenager is all grown up. These days, the 25-year-old works in pest management by day and croons country music by night. But the long “alligator scar” remains—as does Sawyer’s sense of humor about his heart condition, tetrology of fallot with pulmonary atresia, a rare condition in which a solid “plate” of tissue blocks blood from moving from the heart to the lungs. “If you think of the valve as a gate, it is locked shut in atresia,” says Wendy Book, director of Emory’s adult congenital heart center.

Sawyer’s heart defect has necessitated six surgeries to date. The most recent—to replace that cadaver valve—was scheduled in the middle of his graduate school semester last year. The conversation with his professors was short. “I just said, ‘I have to have a little minor surgery,’” Sawyer says. “I think it’s funny when they find out later.”

Sawyer has had plenty of time to practice understating his condition. But the scar that stretches from his neck to his stomach tells the full story: At his birth in South Georgia, his doctors realized that his pulmonary valve had failed to form and that he wouldn’t survive without immediate intervention. He was rushed by helicopter to Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, where doctors put in a shunt to open up the newborn’s valve area and provide his lungs with oxygen. He’s been at Emory ever since. These days, he gets checkups at Emory’s adult congenital heart center.

“After many years, if left untreated, the pulmonary insufficiency eventually results in right ventricular dilation, irreversible right heart failure, and life-threatening arrhythmias,” says Brian Kogon, who performed Sawyer’s latest surgery, replacing a pulmonary valve to prevent such complications.

“Andrew is a model patient, a fantastic person with an amazing spirit for music and for life,” Kogon says. “People like Andrew make it easy to get up every day and do what I do.”

Kogon and his team expect this latest valve to last for the next two or three decades, allowing Sawyer to continue to live an active, healthy life. And now that Sawyer has healed from surgery, he is not wasting any time getting back to his comic roots. His new heart valve has even given him new material to exploit.

“This time they used a cow valve,” says Sawyer. “I ride by steakhouses and get a little teary-eyed.”—Dana Goldman

|

Web Connection: For more info, call 404-778-7777 or visit emoryhealthcare.org/connecting/healthconnection.html. |

||||