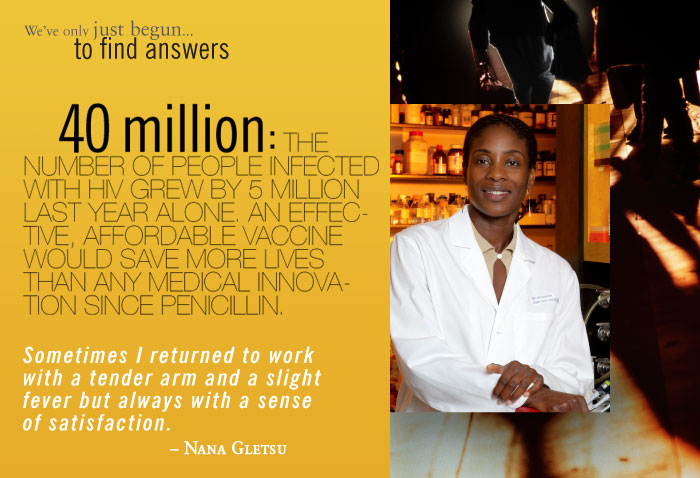

One such study volunteer is Emory scientist Nana Gletsu. She sees the havoc wrought worldwide by AIDS, especially in the poorest nations, and she understands the power of research. The Ghana native also knows that minority groups are often under-represented in clinical trials, a fact that makes differences in drug response among people of

different

genetic backgrounds harder to pinpoint. That’s

why she spent almost two years regularly dashing from Emory’s Department

of Surgery, where she works, to the small Hope Clinic tucked away in downtown

Decatur. As a participant in a study of an HIV vaccine developed by Merck,

she was at no risk of infection from the vaccine, which contained only one

of the six proteins from HIV. The phase 1 trial, part of the FDA-mandated

process to test drugs in human volunteers before they are allowed for use

in the general population, was designed to determine if the components of

the vaccine are as safe in humans as they had been shown to be in animals.

different

genetic backgrounds harder to pinpoint. That’s

why she spent almost two years regularly dashing from Emory’s Department

of Surgery, where she works, to the small Hope Clinic tucked away in downtown

Decatur. As a participant in a study of an HIV vaccine developed by Merck,

she was at no risk of infection from the vaccine, which contained only one

of the six proteins from HIV. The phase 1 trial, part of the FDA-mandated

process to test drugs in human volunteers before they are allowed for use

in the general population, was designed to determine if the components of

the vaccine are as safe in humans as they had been shown to be in animals.

“Sometimes I returned to work with a tender arm and a slight fever but always with a sense of satisfaction,” says Gletsu. She since has become active in Emory’s community outreach to promote AIDS prevention and participation in clinical trials.

Gletsu is one of 300 healthy volunteers from the Emory and Atlanta community who have helped the Hope Clinic conduct more than a dozen clinical trials of vaccines for AIDS and other diseases. The clinic is part of the Emory Vaccine Center, which was established with support from the Georgia Research Alliance and is one of the largest programs in the country developing and testing vaccines for infectious diseases.

| Next

chapter: to transform health and healing>> |

||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Copyright

© Emory University, 2006. All Rights Reserved

response. This vaccine proved remarkably effective in protecting

rhesus macaques against a particularly virulent form of simian

HIV. The results made believers of scientists who once

doubted the DNA approach, won FDA approval for human trials

of her vaccine, and bestowed virtual rock-star status on the

unfailingly modest Robinson. Her DNA/poxvirus vaccine

is now considered among those most likely to succeed in helping

control the HIV/AIDS pandemic.

response. This vaccine proved remarkably effective in protecting

rhesus macaques against a particularly virulent form of simian

HIV. The results made believers of scientists who once

doubted the DNA approach, won FDA approval for human trials

of her vaccine, and bestowed virtual rock-star status on the

unfailingly modest Robinson. Her DNA/poxvirus vaccine

is now considered among those most likely to succeed in helping

control the HIV/AIDS pandemic.