First, it makes possible expansion of class size, by 15% in 2007 and by 30% in 2015, a year in which the United States is projected to have a shortage of more than 200,000 physicians.

Second, it permits implementation of a totally revamped medical curriculum, which will take advantage of dramatic changes in technology: for example, allowing students in the anatomy dissection laboratories to simultaneously view MRIs

and other images of what they are dissecting.

and other images of what they are dissecting. Third, the building's highly sophisticated patient simulation spaces will boost Emory's leadership in this arena. For early-phase students, fully equipped examination or emergency room venues will provide realistic settings for "patient" encounters enacted by robots or actors. Meanwhile, more experienced students will practice minimally invasive surgery and other laparoscopic and robotic procedures in specially designed simulation laboratories. Virtual reality technology will allow space to be manipulated one moment to resemble a neuro-ICU and the next, a gymnasium crowded with disaster victims—or almost any other patient care setting these future doctors are likely to encounter.

Fourth—and this is something that the school's forefathers would especially appreciate—the building radiates regard and concern for students. A student commons will be the first-ever designated gathering place on campus where an entire medical school class can be together at once, while spacious student lounges and quiet nooks and crannies will allow for a variety of study styles. Students and faculty alike can grab coffee and sandwiches and, it is hoped, easy interactions. A beautiful atrium, filled with natural light, is part of an effort to create human space that enhances learning.

| Next

chapter: Advances in Research>> |

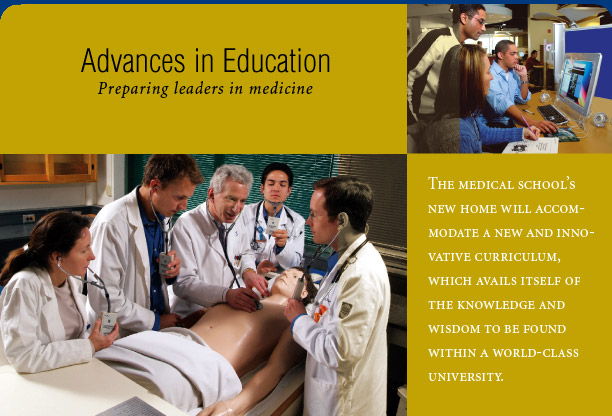

Most traditional medical curricula, including the one being replaced at Emory, begin with two years focused on basic sciences such as anatomy, biochemistry, and physiology. At the impetus of its own basic science faculty, Emory's new medical curriculum begins first with a focus on the whole patient before proceeding down to cells and molecules.

This curriculum has four phases. In phase I, called Foundations of Medicine, basic science and clinical faculty work together to teach the fundamentals of science within a clinical setting. Students engage in clinical experiences from day 1, working in small, problem-solving groups and in teams with physicians and other clinical colleagues. This whole-patient approach provides a conceptual framework of the human body as the curriculum proceeds from the major systems and organs to how the body interacts with its environment at the cellular and molecular level. Elective time is available, and volunteer experiences are expected.

The more discipline-based blocks of the next phase, Applications of Medical Science, continue students' immersion in clinical experience, with strong mentoring and continual assessment of core competencies.

During the Discovery phase, students become involved in research and consolidate their training as lifelong learners. For many students, this five- to 10-month phase will result in their first presentation at a national meeting or publication in a peer-reviewed journal. For some, it may expand to a joint MD/PhD, MD/MPH, MD/MBA, or other degree.

The final Translation of Medical Sciences phase includes sub-internships in key areas, electives in others, and a mandatory Capstone Course to integrate the previous four years, provide updates on the most recent scientific and medical advances, and re-emphasize often-overlooked issues, including how to work with other health professionals; medical, legal, economic, and ethical principles; and cost-containment principles.

Emory has 61 MD/PhD students. Some of these are in a joint program with Georgia Institute of Technology, with which the medical school shares a biomedical engineering department that is a leader nationally in research awards from the National Institutes of Health. The medical school also has 16 MD/MPH students and 390 students in five allied health programs, including a physician assistant program ranked third in the nation by U.S. News & World Report and a physical therapy doctoral program ranked eighth.

Copyright

© Emory University, 2006. All rights reserved