|

|

| |

|

|

| |

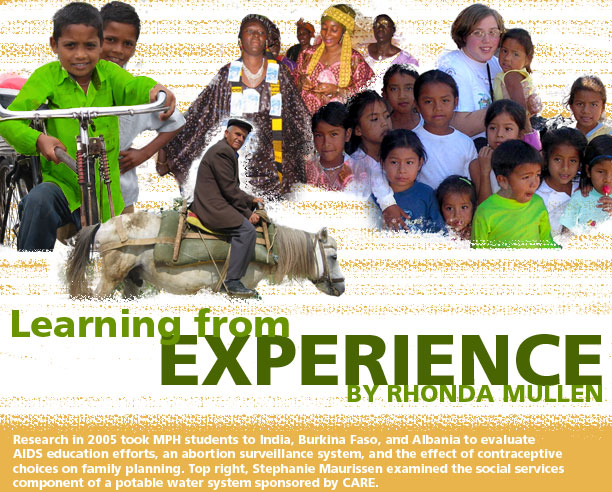

Contaminated

water in tsunami-ravaged Indonesia, HIV in Africa, family planning

in India: MPH students learn vital lessons about public health in

the field. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Stephanie

Maurissen was on the way to Bolivia to help clean up a

river contaminated by metal from a silver mining operation when

a coup overturned the government and politicized the decontamination

project. She had to make new plans—fast.

“Flexibility, flexibility, flexibility,”

says Deborah McFarland in listing the most essential quality in

doing international field study. “Nothing ever works the way

you think it will. You have to adapt.”

McFarland, associate professor in

the Hubert Department of Global Health, directs the Global Field

Experience (GFE) program, in which Maurissen participated this past

summer. “The field experiences are a testing ground for students,”

says McFarland. “Some get verification that they have found

their niche. Others come back and say this isn’t what they

want. These experiences also put students in the trajectory of their

role models. They help shape the next generation of public health

advocates, policy-makers, and researchers. That’s a legacy.” |

|

| |

|

|

| |

INSPIRATION

IN BURKINA FASO: SALLY HONEYCUTT |

|

| |

The

Scenarios from Africa project takes the best ideas from

African teens about how to prevent AIDS and puts them on film, directed

by internationally acclaimed artists. Originating in Senegal, Mali,

and Burkina Faso, the HIV/AIDS education project for young people

has now spread to 35 countries in Africa. Sally Honeycutt headed

to Burkina Faso this summer to evaluate the impact of the films.

In Titao she found inspiration. It

came in the person of Konfé Fatao, a local teacher and AIDS

activist. Titao is a remote village with no electricity, and Fatao

is able to show some of the 28 Scenarios films only when

he has gas for a generator. However, when there is no gas, he is

still using the content of the films to spark discussions about

AIDS with his students. He acts out scenes. He quotes dialogue.

He asks questions.

Through Fatao, Honeycutt visited villages

even more remote than Titao to hold focus groups with Africans between

the ages of 15 and 24 who had viewed the films. She wanted to find

out what the young people thought of what they’d seen. Which

scenarios seemed the most real to them? What situations existed

in their own communities that led them to confront AIDS? The most

common theme that emerged from this focus group and others Honeycutt

conducted was a prevalence of transactional sex, ranging from sex

between a girl and boyfriend who brought her gifts to sex between

a girl and an older man in exchange for a commodity such as a cell

phone.

Honeycutt also observed eight screenings

of Scenarios to see how partners were using the films.

She found a great variation in use, with a frequent discrepancy

between an ideal and actual use of the films. Whereas Fatao was

an inspiring presenter, other facilitators lacked training and support

to lead effective discussions.

Previously, Honeycutt had served in

the Peace Corps as a maternal child health educator in Gabon in

central Africa. The reason she returned to Africa—in fact,

the reason she enrolled in the MPH program at the RSPH—was

to get missing skills. While she was well versed in program management,

she wanted to add project evaluation and research skills to her

experience and hone her ability to apply theory. This field experience,

funded by an O.C. Hubert Fellowship in International Health, allowed

her to do just that. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

LESSONS

FROM THE TSUNAMI: ASTRID SUANTIO |

|

| |

By

the end of the day in Aceh, Indonesia, Astrid Suantio would have

a sore throat. She was there to evaluate and monitor a point-of-use

water intervention in relief camps for displaced people in an area

hardest hit by the December 2004 tsunami, but her fluency in the

local language made her a frequently sought translator.

After the tsunami, these camps opened

with temporary housing consisting of 12-room barracks, with five

to 12 people per room. The high population density contributes to

an increased risk of outbreaks of infectious diseases. A lack of

clean drinking water makes diarrheal disease a particular concern

in the camps.

Suantio, supported by the Eugene J.

Gangarosa Scholarship Fund, was evaluating an intervention developed

by CDC scientists and provided by CARE International Indonesia called

the Safe Water System (SWS). The SWS consists of water disinfection

with chlorine, safe storage in narrow-mouthed containers to avoid

recontamination, and behavior change communication. During three

months in Aceh, Suantio took surveys throughout the Aceh province

to see how people were implementing the SWS in emergency conditions.

Working with colleagues, she went into homes to process water samples,

test for E. coli, and interview people about use of the SWS. She

gave workshops on the SWS for local nongovernmental organizations

and community leaders, and she helped CARE with a hand-washing project

for people living in the camps.

“The most valuable life lesson

I got in Aceh is that human beings are incredible,” says Suantio.

“They have the greatest capability to cope with pain and move

on with life. Even though I heard many stories about the tsunami

from the affected people themselves, not one person that I met still

dwelt on the sadness caused by the tsunami. Yes, they talked about

it and still mourned their loved ones, but they were also optimistic,

trying to rebuild Aceh and their communities as fast as they could,

believing the new Aceh would be better than before.” |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

| |

On-the-job,

in-the-field training |

|

| |

|

|

| |

The

Global Field Experience (GFE) awards partially support

field research around the globe for 45 to 55 students each

year. While many students arrive on campus with previous international

experience, the GFE awards allow them to apply newly acquired

public health knowledge and skills to real-life health settings

and challenges worldwide. Working on a public health project

in the field gives students value-added, practical skills

that will enhance their future careers, says Deborah McFarland,

who directs the program.

These awards represent one of

the distinguishing hallmarks of the global health program

in the Rollins School of Public Health. “Clearly one

of the things that differentiates Emory is the global field

experience,” says McFarland.

|

|

| |

| |

Supported by three endowments—the

Eugene J. Gangarosa Scholarship Fund, the Anne E. and William

A. Foege Global Health Fund, and the O.C. Hubert Fellowships

in International Health—the GFE awards usually cover

airfare, Medevac insurance, and a portion of living expenses

to enable students to gain international field experience.

Often students procure additional support from sponsoring

organizations. And as a group, they raise funds through the

annual sale of a calendar featuring photos taken during the

previous field experiences. Last year this RSPH Student Initiative

Fund contributed $9,000 to the GFE program, sending eight

students abroad for research.

A recent commitment by the Hubert

Foundation will double its endowment for GFE awards, allowing

more students to participate. Maya Ravani applauds that move.

She evaluated a clean water campaign in Kenyan schools this

summer and is continuing to help the CARE-affiliated project

develop a water curriculum for teachers. “Without this

support, I wouldn’t have been able to go,” says

Ravani.

Not only does the global field

experience come with financial support, it also jump-starts

completion of the master’s thesis. The application process

is thorough, requiring potential participants to choose a

project and make the networking connections they will need.

Students are helped in that networking by a faculty with connections

worldwide. Finally, the field experience is the first step

in establishing a global health career, where experience abroad

is a prerequisite.

For more information on supporting

a global field experience, please contact Kathryn Graves,

assistant dean of development and external relations, 404-727-3352,

kgraves@emory.edu. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

PLANNING

FAMILIES IN INDIA: JENNIFER SCHARFF |

|

| |

When

Jennifer Scharff was working as a Peace Corps volunteer in Togo,

she saw four girls die of self-induced abortions. By contrast, this

past summer, she worked on reproductive health in India, where abortion

is legal.

For her global field experience, Scharff,

a Woodruff Scholar at the RSPH, chose to study women’s decision-

making power and perceptions of contraceptive methods in rural India.

Through surveys, focus groups, and interviews, she assembled a reproductive

health portrait of families in Pune in the Maharasta region, gathering

information about contraceptive knowledge and attitudes.

Working out of the Vadu Rural Health

Program, she found a fertility rate of 2.8 children per family.

Currently 80% to 90% of all contraceptive use in India is female

sterilization, reflecting Indira Ghandi’s push for it in the

1970s. The government also offers birth control pills, condoms,

and IUDs free of charge and supports a media campaign encouraging

families to limit children to two. A woman typically lives with

her husband’s family, although, as Scharff found, that trend

is starting to change in Pune as the economy is improving (particularly

when wives don’t get along with their mothers-in-law).

“I saw things changing right

before my eyes,” Scharff says. “The middle class is

small, but it is growing quickly.”

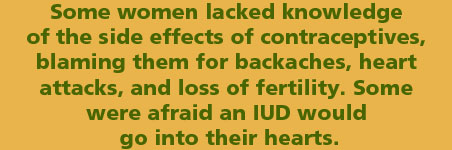

During her study, which was supported

by a Hubert Fellowship, Scharff discovered a lack of contraceptive

education by physicians. Some women lacked a knowledge of the side

effects of contraceptives. They blamed contraceptives for backache,

heart attacks, and loss of fertility. Some of the women were afraid

an IUD would go into their hearts. “The approach of doctors

to counseling about contraceptives is, ‘Don’t ask, don’t

tell,’” says Scharff. She also found that contraceptives

were not used for family planning to space children—something

that she would recommend.

Scharff plans to return to work in

both India and Africa, and she remains committed to reproductive

health in the developing world. That’s a big step for a Memphis

native whose parents never had passports until their daughter began

working overseas. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

WATER

EFFORTS IN KENYA: MAYA RAVANI AND RACQUEL STEPHENSON

|

|

| |

The

Safe Water System was working so well on a small scale in Kenya

that CARE decided to dramatically ramp up the effort in schools

in the Nyanza province this year. With connections arranged through

the Emory Center for Global Safe Water, Maya Ravani headed over

this past summer to assist the organization in evaluating the effort.

She wanted to see if schoolchildren were effective promoters of

safe water handling and proper hand washing to their classmates

and families. But what she found was a project big on enthusiasm

by its partners but short on staff and resources—only one

field officer to implement the program at all 45 schools, only one

truck to transport the oversized storage containers for holding

disinfected water, schools located so far apart and on such rough

roads that only one or two could be visited in a day, and intermittent

outages of electricity.

Racquel Stephenson went to the same

locale as Ravani, but she worked with hospitals rather than schools

to evaluate implementation of the SWS. The program was launched

there in 2004, and she wanted to see whether the nurses’ teaching

practices and utilization rates had changed. She faced her own challenge

when a nursing suspension by the government in Siaya put the project

on hold, giving her no ongoing effort to evaluate.

Both students—supported by the

Gangarosa Fund—decided to change gears. Ravani worked with

baseline data previously collected and pitched in to help the field

officer implement the program. Stephenson decided to supplement

her one-year follow-up with a population survey to see how many

people had received information about the SWS and to determine the

sources of that information.

“I had a totally different idea

of what I’d do,” says Ravani, “but you can’t

really know what’s going on 7,000 miles away until you get

there.” She is continuing to help CARE Kenya in developing

an age-appropriate curriculum for the SWS that can be replicated

in other regions.

Stephenson returned from her first

overseas research experience confident that she has evaluation skills

that can be applied to future assignments. “The organizers

allowed this to be my project. They were stakeholders, but this

project became my baby,” she says. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

FIELD

NOTES |

|

| |

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

MAPPING

CHAGAS DISEASE IN LATIN AMERICA: AMY KRUEGER |

|

| |

Amy

Krueger found her global field calling in Guatemala, working to

help eradicate a devastating parasitic disease.

This past summer with the support

of the Anne E. and William A. Foege Global Health Fund, Krueger

worked with the International Development Research Centre (IDRC)

and the Laboratory of Applied and Medical Entomology (LENAP) on

a project to prevent Chagas disease. Chagas is transmitted through

the triatomine parasite, which is found only in Latin America. The

disease produces flulike symptoms, and in its chronic form, it can

lead to lesions in the heart, esophagus, colon, and peripheral nervous

system. More than 100 million people, or 25% of the inhabitants

of Latin America, are at risk of being infected with the parasite,

and in Guatemala, 730,000 people are affected, with 30,000 new cases

each year.

LENAP and the IDRC are taking an ecological

approach to decrease infestation by the triatomine parasite. Researchers

at these organizations believe that changes to the ecosystem can

lessen the impact of the disease. The project on which Krueger worked

encourages the replanting of natural habitat for the wild animals

on which these parasites normally feed.

Krueger’s specific research

role was to record the latitude and longitude points on each house

in the two study villages of La Brea and El Tule. She took GPS coordinates

on approximately 300 homes, mapping each house and collecting information

on the types of vegetation. She also collected plant samples in

the Guatemala countryside to document dominant species. With this

information along with earlier collected data on socioeconomic status

and variables such as the presence of chicken coops, she is now

completing maps and a spatial analysis of the high risk factors

for contracting Chagas.

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

PORTABLE

WATER FOR ECUADOR: STEPHANIE MAURISSEN |

|

| |

As an intern at CARE headquarters in Atlanta in the water sector,

Stephanie Maurissen read a lot of reports from the field that she

didn’t understand. They seemed too idealistic to be true.

But after a summer of studying the implementation of an actual water

system in Ecuador, she changed her mind.

Maurissen’s summer field experience,

supported by the Gangarosa Fund, gave her the context she needed.

She learned that two obstacles to implementing water systems in

Latin America are sustainability and ownership. In the past, agencies

have installed new potable water systems, only to find them broken

after a year or two with no back-up plan for maintenance and no

money for repairs. By failing to involve the local community in

the installation and maintenance of the system, agencies miss an

opportunity to give ownership to the people who will use the system.

CARE was trying to avoid those pitfalls.

The organization was building deep wells and installing pipelines

to bring water into homes as well as offering hygiene education.

It required the community members themselves to provide the manual

labor for the project—no small requirement considering the

work entailed in chiseling miles of beds for pipes into granite.

In turn, CARE not only provided the initial expertise for installing

the system but also trained a local operator who could fix it when

it broke down. CARE also instituted a tariff system from $0.80 to

$2.00 per month for water usage, the money being banked for future

repairs.

Maurissen evaluated the social services

component of the CARE study, finding that the implementation in

Ecuador was working well. She synthesized previous evaluation documents

into one comprehensive guide, developed a community questionnaire

to evaluate the project, and tested the evaluation tool in six communities:

three with potable water systems and three that are currently on

the waiting list for these systems. She found the time community

members saved in not having to carry water into their homes was

being funneled into a microenterprise set up by the community.

In the course of her research, Maurissen

also discovered a career calling to improve water systems. She’s

already begun by setting up a water alliance in Latin America.

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|