In BriefChildhood abbreviated | Public health nursing advocate wins Hatcher Award Chronicling a betrayal of trust | Environmental health in action | Families count | Real Guns

The three-year, $1 million study will examine the health status and concerns of inmates soon to be released from four prisons. It will also evaluate the effectiveness of HIV education programs conducted both by other inmates and by prison administrators.

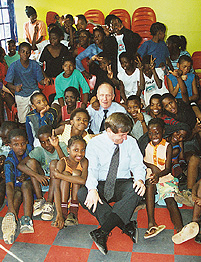

Braithwaite says the United States can learn from South Africa as well. Prisons there offer inmates easy access to condoms. Only two US prison systems--Mississippi and Vermon--now do so. Keith Klugman, RSPH professor of international health, also has work ongoing in South Africa. Klugman, who joined the RSPH faculty last year, continues to serve on the faculty of the University of Witwatersrand in South Africa and directs the Pneumococcal Disease Research Unit of the South African Medical Research Council. He is now working on a study of pneumococcal vaccine among 40,000 children in Soweto, many of whom are HIV positive.

A brave new hope Twenty years after scrawling "Hot Stuff" across a CDC report about five mysterious cases of pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in Los Angeles, RSPH Dean Jim Curran is still where the action is in the fight against AIDS. Researchers at the Emory/Atlanta Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), where Curran is principal investigator and director, recently developed what has been hailed as the "most promising AIDS vaccine yet." According to results published in the March 2001 issue of Science, the vaccine prevented AIDS in monkeys infected with a highly virulent hybrid of simian and human immunodeficiency viruses (SHIV). The vaccine stimulated a strong immune response that allowed infected monkeys to maintain a low level of infection while remaining healthy. Lead author Harriet Robinson, faculty member of the Emory Vaccine Research Center and CFAR, says infections were controlled even among groups receiving a low-dose vaccine. This simple, three-step vaccine regimen offered better protection than any other HIV vaccine candidate to date, placing it among the most promising candidates moving toward clinical trials in humans, which will begin next year. The vaccine was given in three steps—two DNA priming vaccines followed by a modified pox virus booster. The vaccine's greatest strengths are its abilities to elicit expression of multiple proteins and to provide memory immune responses several months after inoculation. Many other AIDS vaccine candidates induced immune responses to only one or two proteins expressed by HIV. Robinson's vaccine causes expression of three, potentially increasing the body's ability to recognize and react to the virus. In the two-year study, Robinson and her research team vaccinated 24 monkeys and compared them with a control group. Seven months after the vaccine regimen was complete, the monkeys were infected with SHIV. As expected, all became infected. Response in vaccinated animals, however, was dramatic. The researchers found that after vaccination, the immune system generated large numbers of T-cells specific to SHIV and immune system memory cells. The establishment of these memory cells is vital to the success of any vaccine, because these cells recognize a pathogen long after vaccination.

Rafi Ahmed, director of the Emory Vaccine Research Center, describes the

vaccine study results as a major turning point. "Dr. Robinson has provided

proof of the concept that a vaccine can prevent the development of AIDS."

Health Issues in the Black Community, Second Edition, Jossey-Bass,

2001, By Ronald L. Braithwaite and Sandra E. Taylor

A foreward written by Jesse Jackson Sr. issues an urgent call to action: “These problems and challenges are immense and require the vision of giants, the creativity of geniuses, the energy of genies.... Leave no American behind. Keep hope alive!”

For the study, researchers contacted female offspring, 5 to 24 years of age, born to mothers listed as exposed to PBB in the Michigan PBB registry. Those with earliest menstruation were daughters of mothers with the highest estimated serum levels of PBBs during pregnancy who had also nursed their infant daughters, giving them both prenatal and breast milk exposures. The most highly exposed girls started their periods about a year early, at 11.6 years compared with 12.7 years for less-exposed girls. This is the second study to associate early puberty with exposure to a specific chemical. The first study, published in Environmental Health Perspectives, associated precocious puberty in young girls in Puerto Rico with plasticizer chemicals.

The RSPH study—funded by the National Institute of Environmental Health

Sciences and the US Environmental Protection Agency—was a

collaboration between Emory, the Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention, and the Michigan Department of Community Health.

Annette Frauman, an advocate for public health nurses everywhere, received

the Charles R. Hatcher Jr., MD Award for Excellence in Public Health last

June.

“I grew up in rural Georgia, and I'm keenly aware of how few educational opportunities there are for nurses and women in rural areas,” she says. “I've felt the isolation that rural public health nurses feel as they go about their duties.” Frauman has worked in pediatric nephrology for many years and is now conducting a study to help children with end-stage renal disease become more independent.

RSPH created the annual Hatcher award to recognize a faculty member of The

Robert W. Woodruff Health Sciences Center who exemplifies excellence in

public health. Hatcher is former vice president for health affairs and

former director of the health sciences center.

"Medicalizing public health problems can be disastrous...," she said. "AIDS became a 'medicalized' problem—first with the advent of AZT and in 1996 with HAART drugs. This shifted the epidemic in this country from one viewed as a collective disaster to one seen as an individual treatment paradigm." Meanwhile, the AIDS epidemic has spread unchecked in sub-Saharan Africa, where there is little or no access to treatments. In the South African state of Kwazulu Natal, 45% of the adult population is estimated to be HIV positive, Garrett said. At the University of Nairobi in Kenya, a recent study showed that 30 percent of students there are HIV positive. "If this were the case in America, wouldn't we have declared it an international catastrophe?" she asked. Scientists must work to understand why the disease has spread so rapidly in some areas and not in others, she said. "West Africa is successfully holding its HIV rates down, while in the east and south the epidemics keep growing in truly mind-boggling proportions. Families, villages, clans, and cultures are being decimated." Public health approaches are the best way to battle AIDS in places like Russia as well, said Garrett. The Russian Ministry of Health estimates that by the year 2015, 14 million people there will be HIV positive—roughly 10% of the population. Garrett said HIV is spread there predominantly by "disillusioned and alienated teens with no hope—drug addicts. A recent University of Moscow study found that 100% of students admitted to injecting narcotics at least once." Other social factors like overcrowded prisons, drug use, sexual behavior, and unsanitary hospitals and clinics also contribute. Garrett's books, The Coming Plague and Betrayal of Trust, discuss some of the most pressing public health issues of the day.

Virginia DeHaan (1927-1988) earned her MPH from the Rollins School of

Public Health in 1977 and was a much-loved faculty member. The DeHaan

lectureship was established in her memory.

The group plans to advocate for a countywide recycling program in DeKalb County, raise awareness about sweatshops in developing countries, and work against environmental racism with the Southern Organizing Committee for Economic and Social Justice.

During the coming year, the group plans to sponsor speakers on

environmental health issues and work with environmental groups across

campus and at other universities. For more information, e-mail Mampilly

at: tmampil@sph.emory.edu

Teens with less parental monitoring are more likely to engage in risky

sex, fighting, and frequent substance abuse, concluded a recent study at

the Rollins School of Public Health.

Published in Pediatrics last June, the study underscores the value

of

family ties in raising healthy, well-adjusted adolescents, says Ralph

DiClemente, lead author and Charles Howard Candler professor of behavioral

sciences and health education.

"Because today's working families are more nuclear and less extended,

there is less supervision inside and outside of the household, creating a

window of opportunity for

adolescents to become involved in risky activities," he says.

The study focused on black female adolescents living in low-income

neighborhoods. DiClemente studied the teenagers' perceptions of their

parents' knowledge about where they spend time outside of school and home

and whom they are with.

Teens whose parents provided less monitoring were twice as likely to have

multiple sex partners and a history of arrest, 40% more likely to have

abused alcohol, and almost three times more likely to smoke marijuana

frequently.

DiClemente says what children think their parents know about their

activities and friends is crucial. The findings also show that few

children perceive fathers to be parental monitors. Rather, most

adolescents said their mother was the heavy.

DiClemente suggests

that parents learn how to balance a teen's desire for autonomy with their

own parental obligation to protect their children from harm.

"Parents can do this

by instilling their own values in the child and providing constant

monitoring of their children's activities and friends to reinforce their

values," he says. "The goal, of course, is that eventually children will

regulate their own behavior."

Real guns

The study included 64 boys aged 8 to 12, whose parents had completed a survey on firearm ownership, storage practices, and perceptions about their children's behavior around guns. The boys were divided into 29 groups of two or three and observed for 15 minutes through a one-way mirror in a room with toys scattered about. Two water pistols and a real .380-caliber semiautomatic handgun were hidden in drawers. Instead of bullets, the real gun contained a radio transmitter that activated a light whenever the trigger was pulled hard enough to shoot. None of the boys knew whether the gun was loaded, and only a few left the room to tell an adult. About 76% of the boys discovered the handgun; 48% of the boys handled the gun; and 25% of the boys pulled the trigger. Afterward, nearly half of the 48 boys who found the gun said they weren’t sure if it was real. Also, more than 90% of the boys who handled the gun or pulled the trigger reported that they had previously received gun safety instruction. More than half of the parents of the boys who handled the gun had previously reported that their children had no interest in guns. The study results affirm the position of the American Academy of Pediatrics that “the most effective measure to prevent firearms-related injuries to children and adolescents is the absence of guns from homes and communities.” It also supports the need for parents with guns in the home to keep their firearms secured away from all children, locked and unloaded.

Forgotten Disease of Forgotten People | Eric Ottesen Interview | Age-Old Questions | Alumni News WHSC | RSPH Copyright © Emory University, 1999. All Rights Reserved. Send comments to hsnews@emory.edu. |