|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

E-mail to a Friend

E-mail to a Friend

Printer Friendly

Printer Friendly |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Highlights:

|

|

|

|

When

emergencies have to wait

Mission possible

A verdict for the common good

Protein pieces of the Parkinson's puzzle

Home

is where the transplant is

Labor of love

The

RUTH effect

Three

strikes

We've

come a long way baby

First sight

Racing for life

Milestones |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

When

emergencies have to wait

Arthur

Kellermann, Emory’s chair of emergency medicine, has watched

emergency departments (EDs) become stretched more thinly year after

year. On any given night, emergency services at Grady and

Emory hospitals reflect the typical problems of emergency rooms

across the country—overcrowding with long wait times, frequent

diversion of ambulances, and resources stretched to the max. In

the United States, ambulances are turned away from emergency departments

on average once every minute, and patients in many areas of the

country may wait long hours or even days for a hospital bed.

For more than a decade, Kellermann

has been an outspoken proponent for improving emergency medical

care, and over the past three years, he has served on a committee

of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) investigating the future of emergency

care in the United States. The committee’s final reports delivered

a devastating verdict and an urgent call to action. In short, the

emergency medical system is (in the words of the committee) “at

the breaking point”—barely able to handle daily caseloads,

much less a surge of casualties from a disaster.

“If we are struggling to deal

with tonight’s 911 calls in city after city across the United

States, how in the world are we supposed to handle an epidemic of

pandemic flu or a major terrorist attack or the next natural disaster?”

Kellermann asked a National Public Radio reporter upon release of

the reports in June.

The critical condition of today’s

emergency medical system stems from insufficient funding and steady

growth in uncompensated emergency care, according to the IOM. In

the early 1980s, federal funds for enhancing emergency response

services declined abruptly, leading to haphazard development of

EMS services. In 1986, Congress passed a law that made emergency

care a right for everyone in the United States, but it provided

no mechanism to pay for this care. Over the next 20 years, patient

volumes increased while hundreds of emergency departments closed.

In 2003, EDs received nearly 114 million patients—a 26% increase

over the previous decade—but the country lost 703 hospitals

and 425 emergency departments during the same period. Despite these

challenges, emergency medical services received only 4% of funding

distributed by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security for emergency

preparedness in 2002 and 2003.

Compounding the problem are the 45

million people in the United States who lack health insurance. Many

who are turned away from other clinical settings because of inability

to pay end up in the emergency room. Another IOM committee on which Kellermann served

calculated that U.S. hospitals and doctors lose billions annually

in uncompensated care of the uninsured, which in turn creates enormous

stress on the health care system. In the 2004 fiscal year, uncompensated

care provided by Emory physicians at Grady totaled $22 million.

(Emory Healthcare provided $51.7 million that year

emergency room. Another IOM committee on which Kellermann served

calculated that U.S. hospitals and doctors lose billions annually

in uncompensated care of the uninsured, which in turn creates enormous

stress on the health care system. In the 2004 fiscal year, uncompensated

care provided by Emory physicians at Grady totaled $22 million.

(Emory Healthcare provided $51.7 million that year

in charity care and $66 million in 2005.)

When hospitals are full, as is increasingly

the case, admitted patients often back up in the ED. When EDs become

dangerously overcrowded, the staff may ask inbound ambulances to

divert to other facilities. In 2003, U.S. hospitals diverted more

than 500,000 ambulances because of overcrowding in the ED. Diverting

ambulance patients from one hospital to another puts additional

stress on patients, family members, and the community, Kellermann

says. And when other hospitals go on ambulance diversion as well,

a community can experience the health care equivalent of a “rolling

blackout.”

Conditions in the Grady ED, which

handles more than 100,000 visits each year, reached a record low

in 2002 and 2003 when, because of crowding, average throughput times

exceeded seven hours and the ED was on diversionary status more

than 20% of the time. To counter those trends, Leon Haley, vice

chair and chief of emergency medicine at Grady, implemented a model

to identify major bottlenecks in patient flow, instituted new diagnostic

test-ordering processes, and improved staff coordination in the

ED’s fast track for people with minor illnesses or injuries.

Those efforts produced results: the ED reduced average time from

arrival to bed placement from 219 minutes to 94, a 57% decrease.

With the support of the Robert Wood

Johnson Foundation and later the Healthcare Georgia Foundation,

Haley also created an ED-based “care management unit”

with seven beds staffed by four nurses and four case managers. This

unit is used to evaluate and treat patients with chest pain, heart

failure, asthma, and hyperglycemia—conditions that would otherwise

mandate hospital admission. While these patients undergo rapid treatment,

case managers teach them how to better manage their health and arrange

follow-up with a primary care provider. The goal of the program

is to decrease the number of short-stay admissions and repeat visits

to the ED.

To promote injury prevention and public

health surveillance, Emory’s Department of Emergency Medicine

is developing programs to reduce the root causes that result in

ED visits, such as child neglect and abuse, firearm violence, and

head injuries and to improve outcomes when emergencies do occur.

Start-up support to develop innovative ideas comes from a fund created

by the Seaman family and their business, Rooms to Go. The partnership

has produced results. For example, Bryan McNally is leading Cardiac

Arrest Registry to Enhance Survival (CARES), an initiative funded

by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CARES is a national

registry designed to help communities across the United States identify

when and where cardiac arrest occurs, which elements of their EMS

system are functioning properly and which are not, and what changes

are needed to improve outcomes. Emory researchers are compiling

and analyzing preliminary CARES data to drive improvements in treatment

in Fulton County, soon to be expanded to all of metro Atlanta, and

ultimately, nationwide.

In another cardiac care initiative,

Emory emergency physicians partnered with Grady and the Emory Heart

Center to improve the prehospital treatment of heart attack victims.

With the support of Medtronic/Physio-Control, Cingular Wireless,

and Nokia, Grady ambulance crews were trained and equipped to obtain

12-lead ECGs in the field and transmit them via cell phone to an

emergency physician at Emory Crawford Long hospital. If the ECG

showed signs of a major heart attack, the patient was offered the

option of direct transport to the cath lab at either Emory University

Hospital or Emory Crawford Long. The pilot program was so successful

that a consortium of Atlanta’s leading hospitals is joining

Emory to expand it throughout the metro area. The initiative will

operate under a new name, Timely Intervention in Cardiac Emergencies

(TIME). Like CARES, TIME has the potential to transform emergency

cardiac care nationwide.

From yet another tack, Emory’s

interdisciplinary emergency nurse practitioner program—offered

through its schools of Nursing and Medicine and one of only four

of its kind in the nation—is helping improve ED patient flow

by training nurse practitioners to provide cost-effective health

care in emergency settings.

According to the IOM report, innovative

solutions like these are needed to strengthen the nation’s

emergency care system. The report calls for reform of reimbursement

policies to reward hospitals that end ED boarding and stop diverting

ambulances. Penalties might be assessed for those that willfully

fail in this area.

The report also calls for a pool of

at least $50 million to reimburse hospitals for uncompensated emergency

and trauma care as well as substantial increases in federal funding

to provide hospitals with resources needed in disasters. And it

recommends the allocation of $88 million in seed grant funding over

five years for pilot projects to promote coordination and regionalization

of emergency care.

If getting the word out helps Congress

open its wallet for emergency care, then Kellermann is doing his

part. Covered in more than 172 news sources across the United States,

including NPR, CNN, the Associated Press, and USA Today, the chair

of emergency medicine may finally have a soapbox tall enough from

which to be heard.

For more details on the report, click

here.

This

fall, Kellermann is on sabbatical as a Robert Wood Johnson Health

Policy Fellow in Washington, DC.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

Mission

possible

The

idea is no small one: to relocate Emory University Hospital to the

east side of Clifton Road alongside a new clinic cluster for outpatient

care, medical faculty offices, and medical research. But

the Emory Board of Trustees is thinking large-scale and long-term,

and in June, it officially accepted the results of a nine-month

feasibility study. Following the recommendation of the Woodruff

Health Sciences Center board, the University’s Board of Trustees

authorized preparation of architectural schematic designs for new

hospital and outpatient facilities that could take as long as a

decade and as much as $2.2 billion to realize. The

idea is no small one: to relocate Emory University Hospital to the

east side of Clifton Road alongside a new clinic cluster for outpatient

care, medical faculty offices, and medical research. But

the Emory Board of Trustees is thinking large-scale and long-term,

and in June, it officially accepted the results of a nine-month

feasibility study. Following the recommendation of the Woodruff

Health Sciences Center board, the University’s Board of Trustees

authorized preparation of architectural schematic designs for new

hospital and outpatient facilities that could take as long as a

decade and as much as $2.2 billion to realize.

The new medical complex will enable

Emory to achieve its vision to transform health and healing in the

21st century, says Michael Johns, CEO of the Woodruff Health Sciences

Center. That vision involves integrated care centered on the patient

with an emphasis on predictive medicine. “These new facilities

will support research, patient care, and medical training in a new

and more nimble way that sets the standard for teaching hospitals

everywhere,” Johns says.

At the centerpiece of the plan is

a new 700-bed hospital that will feature underground parking, a

spacious atrium, and retail shops for the convenience of patients

and visitors. The new hospital will combine beds from the current

84-year-old Emory University Hospital facility and other Emory facilities

on Clifton Road.

However, a new hospital and clinic

are far from a done deal. Several remaining decision points in the

next few years will determine the eventual size and configuration

of the new health sciences complex. “The trustees have made

it clear that we must proceed through this process in deliberate

step-wise fashion with periodic reality checks on funding, feasibility,

and advisability,” says John Fox, CEO of Emory Healthcare.

“We will always be planning many steps ahead, but our ability

to get to the end depends on world-class execution at every stage.

Convenient and accessible transportation for our patients, doctors,

nurses, and staff will be job one, and that’s where we are

starting.”

Beginning in the summer of 2007, the

Turman Residential Center will be demolished to make way for construction

of a 720-space parking deck. That deck, which will connect by a

pedestrian tunnel to the eventual site of the new clinic and hospital,

should be available for use by the summer of 2008. The spaces will

replace parking that will be lost in the physicians and Scarborough

parking decks and in one-third of the Lowergate deck when site preparation

for the new clinic is scheduled to begin.

The hospital and clinic development

are part of a larger ambitious strategy by Emory to enhance the

livability, accessibility, and vibrancy of its campus and the surrounding

community. Goals include restoring a walkable environment, creating

a landscaped public realm, transforming Clifton and North Decatur

roads, and expanding transportation options for the area. Emory

also is making plans to develop a campus in midtown Atlanta encompassing

Emory Crawford Long Hospital.

The mission is large but not impossible.

In the words of Fox, “Over the next 10 years, we will build

an Emory that is a source of pride and hope for everyone who needs

the support of a more accessible, more navigable, and more patient-friendly

health care system.”

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

A

verdict for the common good

Support

for creating specialized health courts is growing. U.S.

Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist and the Progress Policy Institute,

known in the 1990s as President Clinton’s “idea mill,”

have endorsed the concept. So have more than 80 leaders in U.S.

health care, including Woodruff Health Sciences Center CEO Michael

Johns, and a broad coalition of patient advocates and health care

providers, including Emory Healthcare. Known as Common Good, the

bipartisan legal reform group is championing such courts as a way

to restore reliability to medical justice. Support

for creating specialized health courts is growing. U.S.

Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist and the Progress Policy Institute,

known in the 1990s as President Clinton’s “idea mill,”

have endorsed the concept. So have more than 80 leaders in U.S.

health care, including Woodruff Health Sciences Center CEO Michael

Johns, and a broad coalition of patient advocates and health care

providers, including Emory Healthcare. Known as Common Good, the

bipartisan legal reform group is championing such courts as a way

to restore reliability to medical justice.

These health courts would be devoted

exclusively to addressing health care issues, just as existing specialized

courts already focus on taxes or drugs, for example. The hallmark

of the courts would be full-time judges with training in health

care issues, enabling them to define and interpret standards of

care in malpractice cases. Other key features of the courts would

include neutral experts, efficient proceedings to reduce attorney’s

fees and administrative costs, and predictable damages with compensation

for pain and suffering set by a predetermined schedule. State policy

makers would decide jurisdiction and selection of judges.

Six health systems have signed on

to express a strong interest in participating in a pilot project

to set up such courts. In addition to Emory Healthcare, they are

Duke, Jackson Health System at the University of Miami, Johns Hopkins,

New York-Presbyterian, and Yale. Common Good is leading the effort

in partnership with the Harvard School of Public Health and funding

from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

At press time, senators had introduced

a bill to establish pilot courts. To follow the progress, see www.cgood.org.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Protien pieces of the Parkinson's puzzle

Emory scientists are making advances in uncovering the mysterious

function of the protein DJ-1. The ultimate goal for the search?

To find potential cures for nonhereditary Parkinson’s disease

and other neurologic degenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer’s.

The function of the DJ-1 protein is

unknown, but what scientists do know is that abnormalities in DJ-1

directly cause hereditary (familial) Parkinson’s disease.

Approximately 10% of Parkinson’s cases are hereditary forms

caused by a deletion of a gene or mutations resulting from substitutions

of amino acids.

But what causes the other 90% of cases

that are uninfluenced by genetics? Pharmacologist Lian Li

wondered if DJ-1 mutations play a role in nonhereditary (sporadic)

Parkinson’s, too. In research funded by the National Institutes

of Health, she has discovered that DJ-1 in patients with sporadic

Parkinson’s showed signs of oxidative stress, an imbalance

of antioxidants (agents that prevent oxygen from combining with other substances) and pro-oxidants in cells. The

damage included structural changes as the protein accumulated additional

oxygen molecules.

combining with other substances) and pro-oxidants in cells. The

damage included structural changes as the protein accumulated additional

oxygen molecules.

In essence, this imbalance results

in an excess of reactive oxygen species (harmful oxygen-containing

molecules that can cause damage to proteins). These modifications

to DJ-1 caused by the oxidative stress are irreversible and irreparable.

As with familial Parkinson’s disease, structural changes to

the DJ-1 protein in sporadic Parkinson’s signal an abnormality,

leading to eventual degrading and loss of the protein.

“The protein unfolds and cannot

function normally,” Li says. “Not recognizing the unfamiliar

shape of the protein, the cell breaks it down. The end result is

the same: you lose your protein. Any mutation or modification causing

this protein to lose its function will then lead to neurodegeneration

seen in Parkinson’s disease.”

Li and her team are now building on

the research, published in the April 21 issue of the Journal

of Biological Chemistry, to better understand the role of DJ-1.

Based on biochemical analysis, Li believes that DJ-1 may serve as

a protease, a protein-splitting enzyme that activates and deactivates

a protein by cleaving the bonds that connect its amino acids. If

DJ-1 serves as an antioxidant, then the cell may be left unprotected

when they protein is mutated or damaged.

Results of Li’s study

may lead scientists to develop drugs to target DJ-1, thereby stopping

or reversing Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s diseases. In

the meantime, Li suggests alternative health approaches such as

the antioxidants found in green tea or vitamin C supplements as

prevention measures. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Home

is where the transplant is

In

June, the Mason Outpatient Transplant Clinic dedicated a comprehensive,

state-of-the-art clinical and patient education center in Emory

Clinic, more than tripling its former size. The new clinic,

funded by a $1.8 million grant from the Carlos and Marguerite Mason

Trust, features a waiting room that seats more than 80, computer and Internet access for patients, education

classrooms, evaluation suites with multi-media capability, 20 exam

rooms, increased infusion room capacity, advanced biopsy procedure

rooms with high-tech ultrasound equipment, and expanded clinical

lab space.

than 80, computer and Internet access for patients, education

classrooms, evaluation suites with multi-media capability, 20 exam

rooms, increased infusion room capacity, advanced biopsy procedure

rooms with high-tech ultrasound equipment, and expanded clinical

lab space.

“In the early years of transplantation,

the focus was simply to get a surgeon and an organ to save a life,

but this is too narrow a perspective,” says Christian Larsen,

Carlos and Marguerite Mason Professor of Surgery and director of

the Emory Transplant Center. “To truly restore life and health

for the whole person requires a team of physicians, surgeons, nurses,

social workers, infectious disease specialists, psychiatrists, and

dermatologists—matched with an administrative team, financial

coordinators, and more. This clinic gives those teams a home.”

Michael Johns, CEO of the Woodruff

Health Sciences Center, describes the Emory Transplant Center as

“a model of the integrated, patient-center research and clinical

care we are pioneering and perfecting at Emory. Transplantation

is one of the first investments the health sciences center is making

to truly enable the transformation of health and healing.”

In 2005, the Mason Transplant Outpatient

Clinic had more than 17,000 patient visits, including 7,000 lab

visits, 400 infusions, and 10,000 provider visits. With the increased

capacity, the clinic projects more than 20,000 patient visits in

2006 and more than 23,000 in 2007. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

|

|

Labor

of love

“Being

a midwife is the best job in health care,” says Jane Mashburn,

specialty coordinator for Emory’s Nurse-Midwifery Program

and herself a graduate of its first class in 1978. “Midwifery

lets you work closely with patients, take a holistic view of women’s

health and pregnancy, and view labor as a normal process, not a

medical problem.”

Mashburn is not alone in her thinking.

The program’s core faculty are all practicing midwives, who

have taught and worked together for more than 20 years. According

to Mashburn, they provide a personal learning environment that empowers

students, who have one of the highest pass rates on certification

exams in the country. Another marker of success is the program’s consistent top 10 ranking

in U.S. News & World Report (it currently places seventh).

marker of success is the program’s consistent top 10 ranking

in U.S. News & World Report (it currently places seventh).

The Nurse-Midwifery Program in the

Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing also draws on partners at

the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Rollins

School of Public Health, and the Lillian Carter Center for International

Nursing.

For Kitty MacFarlane, who received

both her undergraduate nursing degree and a dual master’s

degree in nursing and public health at Emory, the midwifery program

opened doors to CDC’s Division of Reproductive Health. There,

she works as part of a multidisciplinary team that implements community-based

perinatal surveillance in developing countries. MacFarlane’s

role on the team is to teach midwives how to collect and interpret

surveillance data to improve the use of scarce resources for maternal

and child health program management.

Recently she was awarded funding from

the Gates Foundation to develop a pilot midwife case-management

training program in Afghanistan. The goal of the new initiative

is to introduce safe water systems into the homes of very low birth

weight infants born at a women’s hospital in Kabul. “Training

Afghan midwives for this new, nontraditional role will benefit the

families of these fragile infants, broaden the professional development

of midwives in Afghanistan, and help link the hospital to local

community resources,” says MacFarlane.

Other graduates have chosen to practice

close to where they trained. “Many of our clinical sites are

staffed by alumni,” says Mashburn. “Not many schools

have that.” In addition to working as midwives, the program’s

graduates are involved in careers in health care services research,

nursing education, health care counseling, and community health

education.

This holistic approach to women’s

health reflects the coordinator’s own motivation for entering

the field. “I chose midwifery to be present in a woman’s

life, more than just during her labor,” says Mashburn. “I

wanted to be there for the whole pregnancy.” —Jennifer

Williams |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

The

RUTH effect

An

international team of researchers recently completed a clinical

trial to see if the drug raloxifene could affect the heart health

of more than 10,000 women from 26 countries who had experienced

coronary heart disease or were at high risk for a heart attack.

It turns out that raloxifene, marketed as Evista in the United States

for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal

women, had no significant effect on coronary events in this trial

group. An

international team of researchers recently completed a clinical

trial to see if the drug raloxifene could affect the heart health

of more than 10,000 women from 26 countries who had experienced

coronary heart disease or were at high risk for a heart attack.

It turns out that raloxifene, marketed as Evista in the United States

for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal

women, had no significant effect on coronary events in this trial

group.

However, the study showed positive

impacts in other areas. Raloxifene did reduce the risk of invasive

breast cancer and spinal fractures in the participants, who were

followed for an average of 5.6 years.

Results of the RUTH study (Raloxifene

Use for the Heart) are published in the July 13 issue of the New

England Journal of Medicine. Nanette Wenger, professor of medicine

and chief of cardiology at Grady Memorial Hospital, served as principal

investigator of RUTH at Emory and was the co-principal investigator

for the international study.

“Overall there was no effect

on coronary events—no increase or decrease,” Wenger

says. “The lack of increase is important, given

the adverse coronary events that were seen with estrogen/progestin

therapy.”

The investigators identified several

harmful effects, including an increase in fatal stroke risk and

an increased risk of obstruction of a blood vessel by blood clots.

In deciding whether to prescribe raloxifene, clinicians should weigh

the benefits in reducing the risk of invasive breast cancer and

spinal fractures against the increased risk of blood clots and fatal

stroke, concluded the researchers. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

TOP

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

Three

strikes

Their

cause is unknown, their treatment is difficult, and as of now, their

outcome is questionable. Triple negatives are a newly identified

aggressive form of breast cancer that brings anxiety to women much

too young for such a devastating disease.

Epidemiologist Mary Jo Lund

presented her findings on triple negatives at the recent annual

meeting of the American Association of Cancer Researchers. Preliminary

results of the study indicate that black women may be at higher

risk for worse breast tumors and at an earlier age. Building on

these findings, Lund and a team of researchers from the Rollins

School of Public Health and Winship Cancer Institute are developing a multidisciplinary project to examine triple negative

breast tumors. Key collaborators include Otis Brawley and Ruth O’Regan.

are developing a multidisciplinary project to examine triple negative

breast tumors. Key collaborators include Otis Brawley and Ruth O’Regan.

Triple negatives are characterized

by three biologic components that make this form of breast cancer

difficult to treat. Oncologists base treatment decisions on the

presence of three receptors known to fuel most breast cancers—estrogen

receptors, progesterone receptors, and human epidermal growth factor

receptor 2 (HER2). The most effective agents against breast cancer,

such as tamoxifen and trastuzumab (Herceptin), work by targeting

these receptors. Women with triple negative tumors lack all three.

What is most alarming in the understanding

of this type of breast cancer is its high rate of existence in young

black women. Its chance of occurrence in this population is almost

three-fold more likely than in white women, according to Lund.

Overall, black women are at

lower risk for breast cancer compared with white women. However,

for women under the age of 50, black women are at increased risk

over white women of the same age. And evidence exists that younger

black women have breast tumors with more aggressive features. While

factors such as socio-demographics and systematic disadvantages

may affect the development of these “worst-case scenario”

tumors in black women, the actual cause goes deeper. It reaches

into the genes.

Lund and her colleagues hypothesize

that black women have a genetic disadvantage, which encourages development

of these tumors. The researchers want to learn why this susceptibility

exists. Their multidisciplinary study includes a questionnaire,

blood tests, and collection of tumor samples. It is ongoing at three

Emory-affiliated hospitals in Atlanta among black and white female

patients who live in Fulton and DeKalb counties. These two metro

Atlanta counties account for the majority of breast cancers diagnosed

among black women, particularly those under the age of 50. The researchers

are analyzing tumors and searching for other protein markers, besides

the existing receptors, which occur consistently in triple negatives.

They hope to find other protein markers that occur consistently

enough to open doors for new, protein-targeted treatments. That

approach is good news for women because it will target the tumor

independently, unlike chemotherapy, which “indiscriminately

attacks tumor and normal cells,” Lund says.

Ultimately, the research will give

us a biologic and a non-biologic perspective on this type of breast

cancer, collecting information on genetics, tumor biology, and socio-demographic

factors, she says. “We believe that risk and outcome are inextricably

connected.” —JW

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

We've

come a long way, baby

Used

to be, repair for a broken hip required invasive surgery with a

12- to 18-inch incision, and the replacement of the ball and socket

lasted an average of only 15 years. However, that scenario

has changed dramatically, thanks to recent advances in hip reconstructive

surgery. “With longer-lasting implants and less invasive surgeries,

total hip replacement (THR) now ranks among our most successful

procedures,” says Emory orthopedist Greg Erens.

Emory orthopedic surgeons perform

approximately 600 THRs each year. The American Academy of Orthopedic

Surgeons estimates that more than 193,000 THRs are performed annually

in the United States.

Part of the success orthopedists have

had in extending the life of replacement implants comes from advances

in material science, metallurgy, and manufacturing. Alternative bearing surfaces, such

as the ones Erens uses in his practice, wear less and last longer.

These include cross-linked polyethylene, ceramic-on-ceramic, and

metal-on-metal. By contrast, materials used in previous generations—a

metal ball and polyethylene liner—led to release of small

polyethylene particles as the liner wore out, starting a cascade

of events that could lead to severe bone loss around the hip and

eventually loosening and failure of the implant.

metallurgy, and manufacturing. Alternative bearing surfaces, such

as the ones Erens uses in his practice, wear less and last longer.

These include cross-linked polyethylene, ceramic-on-ceramic, and

metal-on-metal. By contrast, materials used in previous generations—a

metal ball and polyethylene liner—led to release of small

polyethylene particles as the liner wore out, starting a cascade

of events that could lead to severe bone loss around the hip and

eventually loosening and failure of the implant.

Another advantage of today’s

alternative bearings is that patients can be fitted with a larger

head or ball to replace the top of the femur. In the past, larger

head sizes were avoided because they were associated with increased

polyethylene wear, according to Erens. However, the new materials

make it possible to use larger head sizes and thereby increase hip

stability and reduce the risk of a dislocation.

While alternative bearings are more

expensive than standard polyethylene, with ceramic-on-ceramic being

the most costly, the price is minimal when compared to the cost

of a second surgery if the original replacement fails.

Erens and James Roberson, professor

and chair of the Department of Orthopaedics at Emory, are participating

in ongoing studies to track how long this new generation of alternative

bearings will last. Although it is too soon to have final numbers,

their preliminary research is showing positive signs.

In addition to use of innovative materials,

the surgical procedure for THR has undergone dramatic improvements.

THR can now be performed safely and effectively through a minimally

invasive approach with an incision averaging between 3 to 4 inches.

This approach minimizes tissue trauma under the incision and decreases

blood loss. It shortens the surgery time and encourages faster recovery

and rehabilitation. It even eases patients’ anxieties about

the process: a 4-inch incision is less intimidating than an 18-inch

scar.

Erens’s long-term goal is to

deliver the same good news to every THR patient: “Those new

hips will last for a lifetime.” —Stacia M. Brown

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

TOP

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

First

sight

Emory

ophthalmic surgeon Diane Song is the only physician

in Georgia and one of only a few in the Southeast who perform pediatric

corneal transplants.

While the surgery is one of the most

common transplants among adults, few doctors are comfortable applying

it to children. With a high chance

for tissue rejection and only an average one-in-three chance of success in this age group, they have reason for caution.

chance of success in this age group, they have reason for caution.

Yet a successful surgery and recovery

gives a child the possibility of learning to see rather than remaining

partially blind.

For babies born with vision-impairing

conditions due to opaque cornea such as Peter’s anomaly or

scars from infections, corneal transplants allow for proper development

of vision. Without the transplant, the visual center of the brain

is unable to receive stimuli necessary for development of the capacity

to see. At birth, all babies have poor vision, and as the brain

learns to recognize objects, life comes into focus.

“Time is crucial for this surgery,”

Song says. “The window of opportunity is between three and

four months when the baby is first beginning to respond to visual

stimulation. Most of visual brain development occurs during the

first two years of life. By the time a child reaches school age,

it’s too late.”

However, undergoing the procedure

too early also can be devastating. “The younger the baby,

the higher the chance is for tissue rejection,” says Song.

Unlike other transplants, where organs

are difficult to procure and match, patients needing a new cornea

have just a short wait, and the procedure does not require matching

blood types. After surgery, patients start a regimen of medicated

drops (sometimes lasting for life) to prevent tissue rejection,

infection, and glaucoma—a common association with Peter’s

anomaly.

“Parents and caretakers are

crucial for a successful transplant,” Song says. “If

they are good about applying the drops, taking the child for frequent

follow-up visits, caring for contact lenses or glasses, and recognizing

problems early, then the surgery has a better chance of succeeding.”

Song performs between 10 and 12 pediatric corneal transplants a

year.

The corneal transplant is just the

first step in the process of helping a baby see. Following surgery,

a multi-specialty group of medical professionals is involved in

years of rehabilitation. A specialist fits the baby for contacts,

while a pediatric ophthalmologist treats amblyopia, or lazy eye,

often by patching the good eye and thus training the brain to use

the affected eye. Frequently, a glaucoma specialist is part of the

rehab team.

“A corneal transplant doesn’t

give babies perfect vision,” Song says, “but it does

clear a path for them to develop perfect vision.” —JW

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

Emory

Healthcare was in the right place at the right time at

the 2006 Peachtree Road Race. As the medical provider for the world’s

largest 10K event, the Emory/Grady team successfully saved the lives

of two people who experienced heart attacks at the finish line.

Unfortunately, those stats don’t hold on other days in Atlanta,

which has one of the lowest cardiac arrest survival rates in the

nation, according to Eric Ossmann, medical director of Grady EMS.

What is needed to win the larger daily race? A better coordinated

911 communications system, willing bystanders to start CPR before

paramedics arrive, and more strategically placed defibrillators

in communities and the work place with people trained to use them,

says Ossman. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Milestones

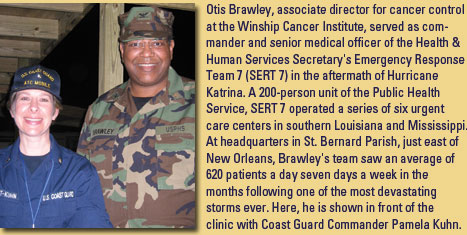

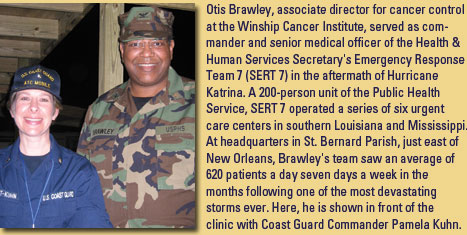

The

Woodruff Health Sciences Center was among four organizations

honored for its relief efforts to victims of Hurricane Katrina in

the Atlanta Business Chronicle’s annual Healthcare Heroes

awards. Of more than 400 patients who were hospitalized in Atlanta-area

facilities in the early days following the disaster, more than 150

were sent to Emory hospitals. The university played an active role

in ensuring that patients were quickly placed in appropriate hospitals,

and faculty, staff, students, and alumni provided a cadre of volunteers,

staffing shelters for evacuees and providing temporary housing. The

Woodruff Health Sciences Center was among four organizations

honored for its relief efforts to victims of Hurricane Katrina in

the Atlanta Business Chronicle’s annual Healthcare Heroes

awards. Of more than 400 patients who were hospitalized in Atlanta-area

facilities in the early days following the disaster, more than 150

were sent to Emory hospitals. The university played an active role

in ensuring that patients were quickly placed in appropriate hospitals,

and faculty, staff, students, and alumni provided a cadre of volunteers,

staffing shelters for evacuees and providing temporary housing.

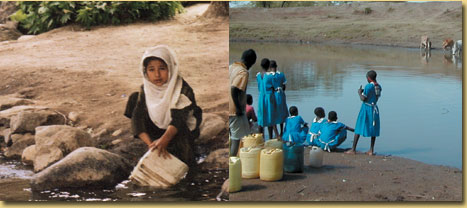

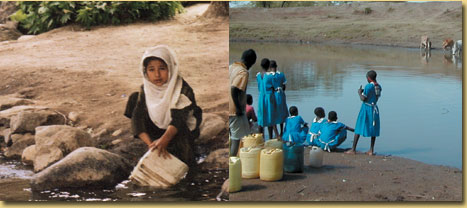

The

Emory Center for Global Safe Water (CGSW) had two winning

proposals in the World Bank’s Development Marketplace 2006

global competition. A competitive grant program that funds innovative,

small-scale development projects that deliver results and show potential

to be expanded or replicated, the Development Marketplace will support

CGSW projects that use income-generating local enterprises to increase

access to safe water and improved sanitation in poor communities—one

in Bolivia and one in Kenya. Only 30 winners out of more than 2,500

proposals were funded. The

Emory Center for Global Safe Water (CGSW) had two winning

proposals in the World Bank’s Development Marketplace 2006

global competition. A competitive grant program that funds innovative,

small-scale development projects that deliver results and show potential

to be expanded or replicated, the Development Marketplace will support

CGSW projects that use income-generating local enterprises to increase

access to safe water and improved sanitation in poor communities—one

in Bolivia and one in Kenya. Only 30 winners out of more than 2,500

proposals were funded.

Emory

University was named the top-ranked university and the

No. 4 institution overall in the Best Place to Work for Postdoctoral

Students 2006 survey, conducted by The Scientist magazine. Emory

University was named the top-ranked university and the

No. 4 institution overall in the Best Place to Work for Postdoctoral

Students 2006 survey, conducted by The Scientist magazine.

Emory University Hospital has been awarded Primary

Stroke Center Certification for its rapid response in diagnosing

and treating stroke patients using a multi-specialty approach and

for efforts to foster better outcomes for stroke care. The hospital

earned the distinction from the Joint Commission of Accreditation

of Healthcare Organizations.

Emory University Hospital has been awarded Primary

Stroke Center Certification for its rapid response in diagnosing

and treating stroke patients using a multi-specialty approach and

for efforts to foster better outcomes for stroke care. The hospital

earned the distinction from the Joint Commission of Accreditation

of Healthcare Organizations.

Solucient, the nation’s leading source of

healthcare information products, has named EUH as one of 100 hospitals

making the greatest progress in improving hospital-wide performance

over five years. The hospital is setting a national benchmark for

consistent improvement in clinical outcomes, safety, hospital efficiency,

financial stability, and growth.

Solucient, the nation’s leading source of

healthcare information products, has named EUH as one of 100 hospitals

making the greatest progress in improving hospital-wide performance

over five years. The hospital is setting a national benchmark for

consistent improvement in clinical outcomes, safety, hospital efficiency,

financial stability, and growth.

The Emory Clinic’s Department of Radiation Oncology

received the 2006 Outpatient Excellence Award for Oncology Centers

from Outpatient Care Technology magazine.

The Emory Clinic’s Department of Radiation Oncology

received the 2006 Outpatient Excellence Award for Oncology Centers

from Outpatient Care Technology magazine.

The Carter Center has received a 2006 Gates Award

for Global Health from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation in

recognition of its work to fight neglected diseases such as Guinea

worm, river blindness, and lymphatic filariasis. The $1 million

award, the world’s largest prize for international health,

honors extraordinary efforts to improve health in developing countries.

The Carter Center has received a 2006 Gates Award

for Global Health from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation in

recognition of its work to fight neglected diseases such as Guinea

worm, river blindness, and lymphatic filariasis. The $1 million

award, the world’s largest prize for international health,

honors extraordinary efforts to improve health in developing countries.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

emergency room. Another IOM committee on which Kellermann served

calculated that U.S. hospitals and doctors lose billions annually

in uncompensated care of the uninsured, which in turn creates enormous

stress on the health care system. In the 2004 fiscal year, uncompensated

care provided by Emory physicians at Grady totaled $22 million.

(Emory Healthcare provided $51.7 million that year

emergency room. Another IOM committee on which Kellermann served

calculated that U.S. hospitals and doctors lose billions annually

in uncompensated care of the uninsured, which in turn creates enormous

stress on the health care system. In the 2004 fiscal year, uncompensated

care provided by Emory physicians at Grady totaled $22 million.

(Emory Healthcare provided $51.7 million that year The

idea is no small one: to relocate Emory University Hospital to the

east side of Clifton Road alongside a new clinic cluster for outpatient

care, medical faculty offices, and medical research. But

the Emory Board of Trustees is thinking large-scale and long-term,

and in June, it officially accepted the results of a nine-month

feasibility study. Following the recommendation of the Woodruff

Health Sciences Center board, the University’s Board of Trustees

authorized preparation of architectural schematic designs for new

hospital and outpatient facilities that could take as long as a

decade and as much as $2.2 billion to realize.

The

idea is no small one: to relocate Emory University Hospital to the

east side of Clifton Road alongside a new clinic cluster for outpatient

care, medical faculty offices, and medical research. But

the Emory Board of Trustees is thinking large-scale and long-term,

and in June, it officially accepted the results of a nine-month

feasibility study. Following the recommendation of the Woodruff

Health Sciences Center board, the University’s Board of Trustees

authorized preparation of architectural schematic designs for new

hospital and outpatient facilities that could take as long as a

decade and as much as $2.2 billion to realize.

Support

for creating specialized health courts is growing. U.S.

Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist and the Progress Policy Institute,

known in the 1990s as President Clinton’s “idea mill,”

have endorsed the concept. So have more than 80 leaders in U.S.

health care, including Woodruff Health Sciences Center CEO Michael

Johns, and a broad coalition of patient advocates and health care

providers, including Emory Healthcare. Known as Common Good, the

bipartisan legal reform group is championing such courts as a way

to restore reliability to medical justice.

Support

for creating specialized health courts is growing. U.S.

Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist and the Progress Policy Institute,

known in the 1990s as President Clinton’s “idea mill,”

have endorsed the concept. So have more than 80 leaders in U.S.

health care, including Woodruff Health Sciences Center CEO Michael

Johns, and a broad coalition of patient advocates and health care

providers, including Emory Healthcare. Known as Common Good, the

bipartisan legal reform group is championing such courts as a way

to restore reliability to medical justice. combining with other substances) and pro-oxidants in cells. The

damage included structural changes as the protein accumulated additional

oxygen molecules.

combining with other substances) and pro-oxidants in cells. The

damage included structural changes as the protein accumulated additional

oxygen molecules.  than 80, computer and Internet access for patients, education

classrooms, evaluation suites with multi-media capability, 20 exam

rooms, increased infusion room capacity, advanced biopsy procedure

rooms with high-tech ultrasound equipment, and expanded clinical

lab space.

than 80, computer and Internet access for patients, education

classrooms, evaluation suites with multi-media capability, 20 exam

rooms, increased infusion room capacity, advanced biopsy procedure

rooms with high-tech ultrasound equipment, and expanded clinical

lab space. marker of success is the program’s consistent top 10 ranking

in U.S. News & World Report (it currently places seventh).

marker of success is the program’s consistent top 10 ranking

in U.S. News & World Report (it currently places seventh). An

international team of researchers recently completed a clinical

trial to see if the drug raloxifene could affect the heart health

of more than 10,000 women from 26 countries who had experienced

coronary heart disease or were at high risk for a heart attack.

It turns out that raloxifene, marketed as Evista in the United States

for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal

women, had no significant effect on coronary events in this trial

group.

An

international team of researchers recently completed a clinical

trial to see if the drug raloxifene could affect the heart health

of more than 10,000 women from 26 countries who had experienced

coronary heart disease or were at high risk for a heart attack.

It turns out that raloxifene, marketed as Evista in the United States

for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal

women, had no significant effect on coronary events in this trial

group.  are developing a multidisciplinary project to examine triple negative

breast tumors. Key collaborators include Otis Brawley and Ruth O’Regan.

are developing a multidisciplinary project to examine triple negative

breast tumors. Key collaborators include Otis Brawley and Ruth O’Regan.

metallurgy, and manufacturing. Alternative bearing surfaces, such

as the ones Erens uses in his practice, wear less and last longer.

These include cross-linked polyethylene, ceramic-on-ceramic, and

metal-on-metal. By contrast, materials used in previous generations—a

metal ball and polyethylene liner—led to release of small

polyethylene particles as the liner wore out, starting a cascade

of events that could lead to severe bone loss around the hip and

eventually loosening and failure of the implant.

metallurgy, and manufacturing. Alternative bearing surfaces, such

as the ones Erens uses in his practice, wear less and last longer.

These include cross-linked polyethylene, ceramic-on-ceramic, and

metal-on-metal. By contrast, materials used in previous generations—a

metal ball and polyethylene liner—led to release of small

polyethylene particles as the liner wore out, starting a cascade

of events that could lead to severe bone loss around the hip and

eventually loosening and failure of the implant. chance of success in this age group, they have reason for caution.

chance of success in this age group, they have reason for caution.