|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Mr.

G, a 45-year-old Mexican immigrant undergoes an employment health

screening and learns he has dangerously high blood pressure. He

is told he will not be permitted to work until his condition is

under control. He goes to a local Georgia emergency room for treatment

and is given a beta-blocker and diuretic, each to be taken once

a day.

One week later, the man presents in

the same emergency room complaining of dizziness. An examination

shows he now has dangerously low blood pressure. He tells the nurse

he has been taking his medicine just as it says to on the labels.

This confuses the care team until a physician fluent in Spanish

asks him how many pills he takes each day. His reply is “22.”

The doctor then explains to his colleagues

that the word “once” (pronounced “ohn SAY”)

is Spanish for 11. Fortunately, the patient’s condition is

stabilized, and he suffers no serious harm. |

|

| |

|

|

|

Six

years ago, this near miss would likely have been just another anecdote

or “learning experience” shared by a few colleagues.

But the day after this incident, a hospital administrator sends

a report to the Georgia Hospital Association’s Partnership

for Health Accountability (PHA) describing what happened and asking

for help in preventing similar incidents.

Although this case is hypothetical,

it’s typical of problems routinely reported to the PHA through

its five-year-old voluntary medical-error reporting system.

Such candor would have been unthinkable

when the system first started, says Vi Naylor, executive vice president

of the hospital association, which launched the partnership in 2000.

“Hospitals were very concerned about confidentiality and reluctant

to share information.”

Envisioning the banner headlines and

civil lawsuits that are so often the result when medical mistakes

are made public, administrators blanched at the thought of voluntarily

sending out sensitive data statewide.

“But over time we developed

their trust,” Naylor continues. “They have seen that

we are able to share information and still maintain the security

of what they send us.” Participating hospitals fill out sentinel-event

forms and receive fast, confidential feedback from other hospitals

on issues requiring urgent attention. They also regularly report

aggregate data on medication errors, incidence of pressure ulcers,

and other common problems to a centralized database. Hospitals can

choose to report information in all categories or just select individual

areas to focus on. The association analyzes this information and

prepares a report comparing each hospital with other institutions

of similar size and capability across the state. Periodic teleconferences

also provide a forum for sharing experiences and strategies.

Today, administrators from across

the state frequently call to suggest ideas for safety alerts and

share concerns and problems they have had, Naylor says. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

A

national model?

Georgia’s

system has the potential to become a model for other states, says

Ken Thorpe, director of the Emory Center for Health Outcomes and

Quality (CHOQ) at the Rollins School of Public Health, which is

working with the GHA to evaluate and improve the system’s

effectiveness.

Formed in 2001, the CHOQ is one of

the largest research centers in the nation devoted exclusively to

evaluating and measuring the quality of health care. Research teams

partner with other groups, such as health care providers, large

group purchasers of health services, and private insurers, to evaluate

problems and design interventions.

“Georgia has, to my knowledge,

the first statewide voluntary reporting system in the country,”

says Thorpe. “If you can make a system like this work—if

it helps reduce medical errors and encourages providers to focus

on areas they want to improve—it can have important national

implications.”

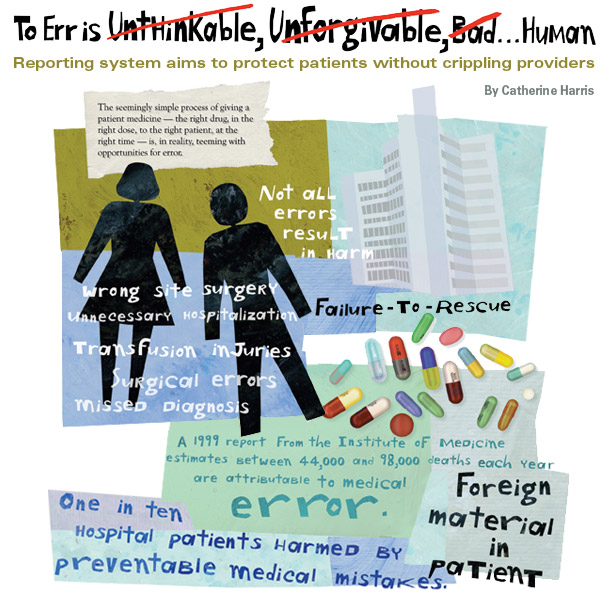

Hospitals across the country have

been under fire since a 1999 report from the Institute of Medicine

estimated the number of people killed by medical errors in hospitals

each year to be between 44,000 and 98,000. The report sparked a

nationwide push for more oversight of health care providers, particularly

hospitals. Several states passed laws establishing mandatory reporting

systems, which publicly rank hospitals by the quality of care they

provide as determined by the number of errors reported.

But many providers believe these efforts

are flawed. Systems designed to measure quality often evaluate small

community hospitals by the same benchmarks used for large, urban

academic medical centers, with the result that neither is evaluated

fairly. Large centers have more resources but also see much sicker

patients and therefore have higher rates of death and other poor

outcomes. Many initiatives also base their rankings on information

obtained from data sets not designed to measure quality of care.

Even the term “medical error”

can be confusing. Clearly, prescribing the wrong medicine or amputating

the wrong limb counts. But what about the patient with limited literacy

skills who takes 10 times the appropriate amount of medication because

he can’t read the bottle’s label? Or a surgical patient

with multiple co-existing medical conditions who gets an infection

while in the hospital? Should poor outcomes that are the result

of many complicated factors be reported as medical mistakes?

At the same time, rising rates for

malpractice coverage give hospitals powerful incentive to hide,

not report, any problems they have with patient safety. In some

states, information about hospital quality-improvement projects

can still be “discoverable” by attorneys in a malpractice

case, who then use the institution’s effort at correcting

a problem as evidence that the institution was at fault.

“In the states that have mandatory

reporting, one of the key concerns is that you don’t actually

get much reporting,” says Thorpe. “Because of liability

concerns, hospitals are reluctant to report information to the databases.

So the institutions that end up with higher rates of mortality,

medication errors, or whatever is being measured are often the ones

who have been most proactive about reporting—they are the

ones paying attention to this. Other hospitals may report lower

rates simply because they are not as vigilant about looking for

mistakes or problems. Some systems actually penalize the behavior

you want to encourage.” |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

How

hospitals miss the mark

Georgia’s

system—with its emphasis on communication, correcting problems,

and finding best practices—has been key to encouraging hospitals

to move closer toward the “culture of safety” necessary

to truly improve, says Bill Bornstein, chief quality officer for

Emory Healthcare, which participates in the reporting system and

has won three of its statewide quality awards.

“In health care, errors are

grossly under-reported,” he states. “And this is not

entirely due to liability issues. The punitive culture also contributes.

Using error-rate reporting comparatively in and of itself incentivizes

against reporting.”

For too long, he says, the nation’s

health care industry has adhered to the belief that mistakes are

the result of individual error and that if all people hired to work

in a health care facility are willing to work hard, are trained

appropriately, and are always diligent, then mistakes won’t

happen.

However, other industries also charged

with maintaining the safety of large numbers of people—notably

the aviation industry—have rejected this kind of thinking.

Aviation now follows total quality

management and quality-improvement processes that focus on identifying

potential problems before they escalate to the point that an accident

can occur. The goal is designing systems and practices to eliminate

the potential for mistakes to occur.

“They accept the concept that

human error is inevitable and predictable in terms of frequency,

and that if you want to avoid errors resulting in harm, you must

design systems to intercept and prevent the occurrences before they

lead to harm,” Bornstein says.

Implementing a culture of safety means

that health care facilities must look at incidents as evidence of

a system failure in need of correction instead of wasting effort

trying to decide whether a bad outcome was the result of a “mistake,”

he says.

A good example of this shift in philosophy

is Emory Hospital’s correct-site surgery protocol, now the

model used by the PHA to develop its statewide guidance for other

hospitals. Emory’s protocol was developed in the late 1990s,

well before the 2003 Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare

Organization’s decision requiring hospitals to implement similar

processes, he says.

The policy is continually reevaluated

and has since been expanded to include all invasive procedures performed

at Emory Hospitals and The Emory Clinic.

“We use a three-pronged approach

ensuring we have ascertained the following for each procedure: (1)

the correct patient, (2) the correct procedure, and (3) the correct

site,” says Jane Vosloh, director of nursing, perioperative

and endoscopic services for Emory Hospitals.

When a patient is admitted to the

unit, providers must verify the person’s identity and ensure

that critical information—particularly a current history and

physical examination and documentation of informed consent—are

included in the chart. Once that process is complete, the patient

is given a colored armband identifying the service to which he or

she is admitted.

The correct site of surgery is also

clearly marked on the patient. And the policy prohibits caregivers

from marking up the surgery site (or proceeding with planning for

the procedure) without reverifying the patient’s identity

and the planned procedure against the information in the chart,

documenting both verifications in the record.

Several checks and balances are built

into the protocol, so that even if one person forgets to perform

a check, someone else down the line has the same responsibility,

says Vosloh.

Finally, prior to the start of the

procedure, a mandatory time-out (officially known as the “call

to order”) is taken for a final check of the patient’s

identity, site of surgery, and the procedure to be performed.

At first, many surgeons resisted taking

all of the steps required, says Vosloh. They considered it a point

of professional integrity to “know their patient” without

repeatedly checking his or her identification.

However, one memorable incident several

years ago convinced many.

“We had a near miss,”

she says. “We got down to the call to order and did the check

and realized we had prepped and draped the wrong side of the patient.”

The error was caught in time and corrected,

but it demonstrated how mistakes happen to even the best providers.

“It also proved that the policy

worked as it was designed to—we caught the mistake and prevented

surgery on the wrong site,” she says. “It made a lot

of people realize we really did need a protocol.” |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Initial

success

Emory’s

CHOQ research indicates that the Georgia system is both improving

the quality of patient care and attracting hospital participation.

Analysis of the data collected over the past five years shows a

35% mean decrease in reported error rates overall, says Kim Rask,

a practicing physician and center researcher who holds joint appointments

in both public health and medicine.

All of Georgia’s hospitals participate

in at least one of the PHA’s reporting initiatives, she notes.

The medication-error initiative is the most popular, and most hospitals

participate in at least two. A recent evaluation of medication-error

data found that 80% of participating hospitals have lowered their

error rates.

“Even for the 20% that saw no

improvement or saw their rates get worse, we are encouraged that

they were willing to report those findings and that they continued

to participate and try to improve,” says Rask. “If everyone

had done better, you would always have to wonder about your reporting.

“So it does seem that people

are putting interventions in place, the vast majority are improving,

and the others have the opportunity to learn from their peers.”

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Building

a Better Report Card |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

When

the Institute of Medicine’s report, To Err is Human,

was released, officials at the Georgia Hospital Association

(GHA) knew they had to act quickly, says association president

Vi Naylor.

“We had a limited window

to develop a reporting system that we felt would be accurate

and would help improve patient safety—or have one imposed

on us from the outside,” she says.

The GHA’s first step was

establishing the Partnership for Health Accountability (PHA)

and getting its Accountability and Health Safety Committee

recognized as a state peer-review organization. Georgia’s

state peer-review law protects information collected for the

purpose of improving patient care from public disclosure and

legal discoverability. The PHA then set up a reporting system

to track medication errors and a select number of other medical

events.

The reporting system is completely

voluntary—hospitals are not punished for not submitting

data, but if they choose to do so, they gain access to information

about how their data compare with those of other hospitals

of comparable size and type, as well as information about

evidence-based best practices. The PHA also sponsors periodic

telephone conferences that allow administrators at different

facilities to share ideas and experiences.

And although the reporting system

is nonpunitive, the PHA does require hospitals that report

medical errors or near misses to submit a plan of correction

and then periodically submit reports detailing its implementation,

says Naylor. “If they do not, they can no longer participate

in the program. So far, we have not had that happen.”

The system provides confidentiality

for reporting of medical errors and sentinel events, but the

GHA also believes public accountability is vital. Each year,

the PHA publishes a report, “Insights,” (available

on their website at www.gha.org/pha) which lists each hospital

by county and indicates whether it participates in both national

and statewide quality-improvement initiatives. A separate

section details whether each hospital meets certain care benchmarks

set by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare

Organizations and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Catherine

Harris is the editor of Momentum. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|