On point

Last fall, the CDC recommended that each acute care hospital in the United States identify personnel to undergo voluntary smallpox vaccination in order to evaluate and care for any initial cases of smallpox at their hospitals following an act of bioterrorism. In December, President Bush announced a plan to offer smallpox vaccinations over the next year to 10 million health care workers, public health personnel, public safety personnel, and Department of Defense employees. Smallpox vaccinations eventually will be available to the general public.

In response to these national policies, Georgia initiated a plan to vaccinate several hundred health care workers. The state plans to vaccinate several thousand health care, public health, and public safety personnel over the next year.

Jeffrey Koplan is vice president for academic health affairs in the Woodruff Health Sciences Center.

David Stephens directs the medical school's division of infectious diseases.

Carlos del Rio is chief of service at Grady Hospital.

Our first consideration

was to assess the risk

of the vaccine.

In this issue

From the director / LettersMed-morphosis

Burden of proof

Big Idea:

Regenerative Medicine

Moving forward

Noteworthy

On Point:

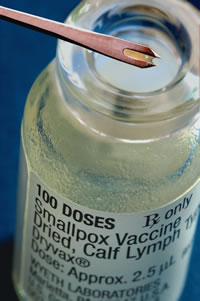

Smallpox, big risks?

by Jeffrey Koplan, Carlos del Rio, and David Stephens

The events of the past two years, including terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and anthrax cases, have made us all uneasy. Could these events have been predicted and avoided? What might come next - what are the odds of a smallpox attack - and given limited public health resources, what is the appropriate amount of funding that should be dedicated to protecting against smallpox, a disease eradicated from the world in 1977? Could these funds be better used to tackle underfunded vaccine initiatives for immediate health threats such as pneumonia, meningitis, influenza, or childhood illnesses? What are the risks to the vaccinated and those exposed to them, such as patients and household contacts? And how should Emory Healthcare respond to new federal and state policies on the issue?

These questions were the subject of lengthy and thoughtful discussions by a team charged with creating Emory Healthcare's smallpox policy. Our task force spanned our facilities and our disciplines -- from emergency medicine and the hospitals to The Emory Clinic, the schools of nursing and public health, and the medical school's division of infectious diseases. Key to facilitating the discussion was Mike Lane, former director of the smallpox eradication program at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Our first consideration was to assess the risk of the vaccine to our health care workers, our patients, and their families. The smallpox vaccine can cause life-threatening complications, particularly for those whose immune systems are compromised by conditions such as HIV/AIDS, cancer chemotherapy, or certain skin diseases including eczema. Routine smallpox vaccination was abandoned in the United States in 1971, six years before smallpox was eradicated. The disease still existed elsewhere, but the risk of the vaccine outweighed the risk of a person contracting smallpox in our country.

Since the pre-1971 period when the vaccine was widely used, the number of patients whose immune systems are compromised, particularly at Grady Hospital, has sharply increased. Likewise, elderly patients at Wesley Woods and young people who have not previously been vaccinated are at increased risk of complications.

A second consideration was to assess the risk of an attack. Which countries might possess the smallpox virus and which might risk retaliation by releasing it? If smallpox were introduced to the United States, how quickly would it spread? Are widespread vaccinations necessary now, and should they be undertaken if an attack has already occurred?

Third, we analyzed how an immunization policy would affect our employees, particularly those involved in direct patient care. Should those vaccinated be removed from clinical settings for up to three weeks following vaccination, when they are infectious and could transmit vaccinia to others? Would they be compensated for this time? Who would be responsible if an employee has a reaction to the vaccine? How would we ensure that those who are immunized receive care in an isolated setting to reduce the risk that they could spread the disease?

Finally, we discussed how to approach the individual components of Emory Healthcare and our affiliate institutions. Our goal was to have a plan to deal with any patient with smallpox who might come to our facilities. Would a "one-size-fits-all" approach work best, or would we need to tailor our policy to address the unique concerns of each facility?

The risk of smallpox to individuals in the Atlanta area seems low, based on comments from state and federal officials that there is no imminent threat of a smallpox attack in Georgia or the United States. Second, vaccinating 5,000, 50,000, or most of the population of Atlanta would not alone stop disease transmission. But if an attack were to occur, the majority of patients could be isolated and vaccinated to limit the spread of the disease. Therefore, we agreed that in the short run, up to 50 employees at Emory University and Emory Healthcare should be vaccinated, including about 20 who are researching vaccinia and related viruses, health care workers to care for CDC employees who might become infected with smallpox or the vaccinia virus used to vaccinate against it, and personnel who will either vaccinate employees or evaluate employees for adequacy of response to smallpox vaccination. All volunteers previously had received a smallpox vaccination.

We decided not to immunize health care providers at Emory Crawford Long Hospital, except for some Emory infectious diseases physicians who are part of the CDC collaboration previously mentioned. While Emory University and Emory Healthcare are not included in the initial phases of Georgia's smallpox immunization program, more people in these categories may receive smallpox vaccinations in later phases of the state program.

We also agreed to support different policies at our affiliate institutions. Physicians at Grady will not be vaccinated initially, since the risk of the vaccine outweighs the benefits in the current environment. Because of major concerns about exposing patients with reduced immune systems to vaccinia, any health care workers at Grady who receive smallpox vaccination will be relieved of clinical duties for 17 to 19 days after vaccination (after the scab falls off and they are no longer potentially infectious). Grady continues to work closely with state and local public health officials on bioterrorism-related issues but is not participating in smallpox vaccinations at this time.

On the other hand, about 50 professionals at the Atlanta Veterans Affairs Medical Center have been vaccinated since they may be called upon to treat cases both here and abroad. And given the increasing number of vaccination programs for active duty military personnel and reservists, VA hospitals expect to see a larger patient population with potential exposure to the vaccine.

Policies at Emory-affiliated hospitals would be united should the state or federal government note an imminent risk of a smallpox attack or if a smallpox case were to occur. If there's a case of smallpox, large-scale immunization of health care workers and the public probably will be demanded and possibly instituted. However, the proven method of outbreak control is "ring vaccination"čidentification and isolation of the case; identification, isolation and vaccination of contacts; and vaccination of those contacts' contacts. This approach breaks the outbreak cycle and helped eradicate smallpox in the past. Fortunately, a smallpox vaccination can be effective if given within four days of exposure to smallpox.

Emory Healthcare will develop a policy for post-event administration of smallpox vaccine after Georgia finalizes a mass vaccination plan. Emory Healthcare will develop a policy for rapid, large-scale immunization of health care workers and members of the general public if a case of smallpox is reported. We are convinced that these policies will benefit all who work at Emory Healthcare and its related institutions and - most important - they will benefit our patients.

Of course, at this point there are no absolute answers, and there are no guarantees. No one can predict the future or guarantee with any certainty that we will be safe against threats to our health and well-being. Great uncertainties exist for both naturally occurring disasters, such as hurricanes, tornadoes, and earthquakes, as well as terrorist attacks. The unknowns must be anticipated wisely -- with prudence and balance.

Copyright © Emory University, 2003. All Rights Reserved.

Send comments to the Editors.

Web version by Jaime Henriquez.