|

|

| |

|

|

| |

E-mail

to a Friend

E-mail

to a Friend

Printer Friendly

Printer Friendly |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Worldwide,

the nursing shortage is increasing at an alarming rate.

In Zambia, 27 of every 1,000 health care workers die of HIV/AIDS.

In the United States, without intervention, the nursing shortage

will reach 1 million by 2012. In Uganda, there are on average only

one or two nurses for every 100 patients. Canada's nursing

shortage is expected to reach 113,000 by 2008.

Certainly migration of health care

workers from poor to wealthier countries that offer better pay and

working conditions contributes to the shortage in many developing

countries. But what causes shortages in wealthier nations? The reasons

are not totally clear-cut, and neither are possible solutions to the global shortage, according to participants

of the 2006 Global Government Health Partners Forum held in November.

possible solutions to the global shortage, according to participants

of the 2006 Global Government Health Partners Forum held in November.

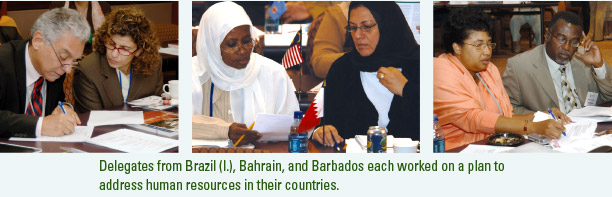

The

conference, hosted by the nursing school's Lillian Carter

Center for International Nursing (LCCIN) and secretariat for the

biennial conference, brought together chief nursing officers (CNOs)

and chief medical officers (CMOs) from 107 countries to address

national and international nursing workforce issues. During the

forum, participants examined workforce roles and responsibilities

and models of collaboration based on current scientific findings,

shared lessons learned, and developed partnership strategies to

enhance their response to public health crises. The CNO/CMO dyads

from each country collaborated to develop a statement of priorities

and a plan of action to address challenges in their own countries.

The

conference built on the successes of the 2001 and 2004 meetings

involving CNOs who developed their leadership skills and built bridges

with one another to address common nursing issues. The landmark

2001 conference marked the first time many CNOs met their regional

counterparts and heard from nursing association and government leaders,

while the 2004 forum was the first of its kind to bring together

CNOs and CMOs in a collaborative, partnership-building effort.

"The

value of the forum extends beyond health leaders detailing the myriad

forces challenging today's health systems," says Dr.

Marla Salmon, secretariat co-chair, dean of the nursing school,and

LCCIN director. "It helped these senior government health

leaders formulate plans to address the challenges and at the same

time create manageable action plans to positively influence the

push-pull factors, such as work conditions, in their own countries

and regions." |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Examining

workforce migration

Workforce

migration begins within countries as health care workers move from

rural to urban areas and then from the public to the private health

sector. Then the pattern shifts from developing countries to industrialized

ones. The effects of such migration on many regions are both profound

and frustrating. Africa, for example, carries 25% of the world's

burden of disease but has only 1.3% of the world's health workers. In Nigeria, 18% of the country's doctors are abroad,

and there are more Malawian doctors in Manchester, England, than

in Malawi itself. After Africa, South America and the Middle East

face the next highest shortage of health care workers, particularly

nurses.

workers. In Nigeria, 18% of the country's doctors are abroad,

and there are more Malawian doctors in Manchester, England, than

in Malawi itself. After Africa, South America and the Middle East

face the next highest shortage of health care workers, particularly

nurses.

"The full magnitude and impact

of the global shortage of health workers is more evident than ever

before," says Dean Salmon. "The crisis cuts across all

sectors of health care with critical shortages of nurses, as well

as doctors. Collaboration within and across the sectors is imperative

in today's world."

Many countries are seeking ways to retain nurses in regions like

these, where the nurses who remain behind are the ones who bear

the brunt of the day-to-day hardships brought on by such shortages.

Dr.

Manuel Dayrit of the World Health Organization (WHO) told attendees

that in countries where the education of nurses is subsidized by

government funds, the government loses its investment when these

nurses migrate. "Use of tax income to fund nurses' training

does not provide a good return on investment in countries whose

graduates migrate to another country because when they leave the

government loses its investment," he said. The Philippines,

by contrast, which has a large private sector to provide nursing

education, produces thousands of nurses, many of whom migrate. In

this instance, while there may be no direct loss of government investment,

the loss of health professionals from migration affects the health

system in other ways.

Other

developing countries, like Malawi, are using foreign aid (from Great

Britain in this case) to raise the salaries of health care workers.

But countries don't always have discretion in spending these

kinds of resources. Dr. Wilmer Beteta Lopez, Nicaragua's CMO,

said the international loan agreement he works under does not allow

him to adjust salary levels for nurses in more expensive regions

of his country, making retention especially difficult in those areas.

While

salary is extremely important, it is not the only issue that drives

nurses even in the poorest countries to migrate or to leave the

health workforce entirely, according to one presenter's research.

Barbara Stillwell is a senior technical adviser with Liverpool Associates

in Tropical Health and runs a project funded by the U.S. Agency

for International Development to build capacity of the health care

workforce worldwide. She studied nurses in Uganda and found fewer

than half of those interviewed said they were satisfied with their

jobs. While satisfaction with their salary was the most common complaint,

nurses also wanted

to feel valued.

"People

find motivation through their workplace relationships," she

said. "Providing motivation is not necessarily expensive,

but you must have management in place to do that. Feeling valued

will influence productivity, performance, and also retention."

Her study found nurses stayed on the job when their workload was

more manageable, when they actively participated in creating a better

health care facility, and when they were recognized for good work.

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

Celebrating

Leaders in Health |

|

| |

|

|

|

There's

a conspiracy among chief nursing officers (CNOs), Dr. Jean

Yan says. There's

a conspiracy among chief nursing officers (CNOs), Dr. Jean

Yan says.

"The CNOs conspire to

make sure you succeed," she said after receiving a 2006

Global Health Leadership Award from the Lillian Carter Center

for International Nursing.

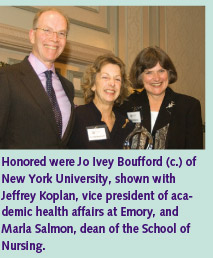

Yan, along with Dr. Jo Ivey

Boufford and Dr. David Nabarro, were recipients of the awards,

handed out at the Global Government Health Partners Forum

2006 in November. The awards are a "celebration of the

partnership of leadership and hope," said Dr. Marla

Salmon, dean of the Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing.

Yan has been a nurse for 35

years and now is Chief Scientist of Nursing and Midwifery

for the World Health Organization (WHO), overseeing policy on nursing and midwifery

services. She served for seven years in the PAHO/WHO Caribbean

Program Coordination Office in Barbados, assisting the ministries

of health with human resource planning, management, and training.

Organization (WHO), overseeing policy on nursing and midwifery

services. She served for seven years in the PAHO/WHO Caribbean

Program Coordination Office in Barbados, assisting the ministries

of health with human resource planning, management, and training.

Boufford is Professor of Public

Service, Health Policy, and Management at New York University.

She has served as Acting Assistant Secretary for Health in

the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, as the U.S.

representative on the executive board of the World Health

Organization, and as director of the King's Fund College in London, a royal charity that supports health and

social services in the United Kingdom.

College in London, a royal charity that supports health and

social services in the United Kingdom.

Only three years after becoming

a physician, Nabarro was off to work as a district health

officer in East Nepal. Since then, he has worked in Southeast

Asia for Save the Children Fund and in Africa for the British

government's Overseas Development Administration. He

joined WHO in 1999 and in 2005 was appointed as the United

Nations Senior Coordinator for Avian and Human Influenza.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

| |

The Global Government Chief Nursing Officers'

Institute, sponsored by Johnson & Johnson, focused specifically

on challenges facing CNOs. Held before the forum, it offered

a neutral and confidential forum for discussion. Several CNOs

were invited to offer lessons they had learned as a CNO. Jesmond

Sharples kindly permitted his to be published. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Ten

Lessons I Have Learned as a CNO |

|

| |

By

Jesmond Sharples

CNO, Malta |

|

| |

|

|

| |

1.

There is no chief without a tribe. 1.

There is no chief without a tribe.

2. There are

no black and white solutions, only gray ones.

3. There are

100 ways of how to do things right, but there is only one

way to do the right thing.

4. Don't

forget the lessons of the past by trying to look too much

into the future.

5. Being a CNO

involves the fine art of tightrope walking between politicians

and the associations without having a safety net to break

one's fall.

6. A CNO ought

to value humankind for what it is and not for what it ought

to be.

7. What you

think is definitely right might well be rightly wrong.

8. Don't

bother too much about whether a glass is half empty or half

full. Be more concerned with whose thirst that water is to

quench.

9. CNOs are

made, not born, but they do die.

10. Don't

forget your sense of humor. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Reducing

the push-pull effect

Though

some developing countries are trying to improve salaries and working

conditions to keep nurses in-country, they are hampered by what

they cannot control: nursing shortages in developed countries. Shortages

in developed countries trigger a push-pull effect. Poor conditions

push nurses out of their home country, while developed countries

pull migrant nurses in to fill their own shortages. For many conference

participants, the question was, "Would nursing migration be

an issue if there were no shortages in developed countries?"

Part of the solution to the push-pull

effect lies in developing cooperative efforts by those countries

on the pulling side of the equation.

When Great Britain, for example, infused

funding into its national health care system in 2000, its leaders

recognized the top goal was to make the country more self-sufficient

in terms of its workforce. Health care leaders began working on

long-term plans to draw British nurses back into nursing and to attract new ones into the profession by fostering a better image

of the country's department of health. To address short-term

needs, they decided to recruit internationally, though only as a

temporary measure, says Debbie Mellor, director of workforce capacity

for the country's department of health. "We were very

concerned if we were going to increase international recruitment

that it be done ethically," she says.

to attract new ones into the profession by fostering a better image

of the country's department of health. To address short-term

needs, they decided to recruit internationally, though only as a

temporary measure, says Debbie Mellor, director of workforce capacity

for the country's department of health. "We were very

concerned if we were going to increase international recruitment

that it be done ethically," she says.

They

developed a voluntary code that independent providers and recruiters

had to sign if they wanted to work with the National Health Service.

The code included a list of "no-recruit" countries where

workforce shortages were especially grave. The code specified that

nurses could be imported from the Philippines and South Africa,

with specific memos of understanding signed with these countries.

"Our

experience in the U.K. is that partnerships can reduce the push

and pull factor," Mellor said. "The bilateral agreements

and programs of cooperation have been very useful and a helpful

way for us to make sure that we're proceeding in an ethical

way."

While

international recruitment was under way, the department also expanded

its number of training locations and promoted the National Health

Service as a model employer in a public campaign. A new, fairer

pay strategy was implemented, and child care needs of the nursing

workforce were addressed, as were issues of violence and harassment

in the workplace.

"We

had an 80% increase in U.K. nurses coming out of training and had

less of a need to rely on international recruitment," Mellor

said. "All of us in our health systems should be aiming for

greater self-sufficiency."

Likewise,

the Philippines began addressing its nursing shortage in a strategic

way, said nursing professor Marilyn Lorenzo, of the University of

the Philippines at Manila. While that country's leaders were

in the process of long-term planning for human resources in health

care, she came forward with data showing inadequate standards and

salary inequity among health care workers throughout the country.

The Philippine master plan for Human Resources for Health now addresses

national competency standards, the promotion of ethical recruitment,

and salary increases, and government nursing positions now outpace

those in the private sector. She told conference attendees that

the next step is to organize a network to implement the plan more

broadly, which over the next five years is expected to result in

an increase of health care workers working in underserved areas.

As

countries like Great Britain heed the call to action to fill their

own vacancies, poorer countries may get some relief from international

recruitment. And there are other positive changes as well, according

to Mireille Kingma, of the International Council of Nurses. Some

studies suggest that workers on average return to their home country

after five years. Additionally, job opportunities are improving

worldwide, especially for women.

But

real change in migration flows, Kingma said, will happen when poor

countries achieve benchmarks of development, such as clean water,

lowered infant and maternal mortality, and a thriving economy. In

that way, regardless of what happens in wealthy countries, developing

countries can start down the path to a self-sufficient workforce. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

Deploying

Data |

|

| |

|

|

|

Any

health care system needs good management to grow its nursing

capacity—an issue Kenya is beginning to address with

the help of the School of Nursing. Kenya's Ministry

of Health lacked accurate data on the number of nurses in

the country. Every time a nurse went for training, a new form

was filled out and stored in a file according to the type

of training. A nurse's name could appear in numerous

files, making it nearly impossible to track an individual

nurse's training. The Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention, with the help of School of Nursing faculty, helped

Kenyan nurses design an electronic database that would assist

the country's health care leaders in workforce management

and policy. While the database is in only one province thus

far, project leaders hope soon to put workstations in Kenya's

seven other provinces. This is a welcome sign in a country

where some studies say that 5,000 nurses are unemployed, and

40% of the nursing positions are vacant because of the difficult

task of becoming registered after training is completed. Any

health care system needs good management to grow its nursing

capacity—an issue Kenya is beginning to address with

the help of the School of Nursing. Kenya's Ministry

of Health lacked accurate data on the number of nurses in

the country. Every time a nurse went for training, a new form

was filled out and stored in a file according to the type

of training. A nurse's name could appear in numerous

files, making it nearly impossible to track an individual

nurse's training. The Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention, with the help of School of Nursing faculty, helped

Kenyan nurses design an electronic database that would assist

the country's health care leaders in workforce management

and policy. While the database is in only one province thus

far, project leaders hope soon to put workstations in Kenya's

seven other provinces. This is a welcome sign in a country

where some studies say that 5,000 nurses are unemployed, and

40% of the nursing positions are vacant because of the difficult

task of becoming registered after training is completed. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|