|

|

| |

|

|

|

arly

in spring semester, when the air is still nippy and the dogwoods

have yet to bloom, Noelle delivers her babies with ease, her feet

in stirrups, her abdomen growing rigid with each contraction, her

cervix opening around the crown of the baby’s head. The deliveries

are textbook, and the babies perfectly arly

in spring semester, when the air is still nippy and the dogwoods

have yet to bloom, Noelle delivers her babies with ease, her feet

in stirrups, her abdomen growing rigid with each contraction, her

cervix opening around the crown of the baby’s head. The deliveries

are textbook, and the babies perfectly healthy. The junior nursing students who receive each baby under

the guidance of the faculty nurse-midwife carry the newborn to the

nearby warming bed with hidden sighs of relief and visible grins

of delight.

healthy. The junior nursing students who receive each baby under

the guidance of the faculty nurse-midwife carry the newborn to the

nearby warming bed with hidden sighs of relief and visible grins

of delight.

But as in real life, things are not

always so easy for the stoic mannequin. By the end of the semester,

her deliveries become longer and more difficult. The baby fails

to shift to the right birth position, and the umbilical cord becomes

wrapped around its neck. Noelle’s late spring babies arrive

with serious problems. Deprived of oxygen, their lips and fingers

slowly become cyanotic, setting off the code alert that brings the

now more advanced students racing to the bedside.

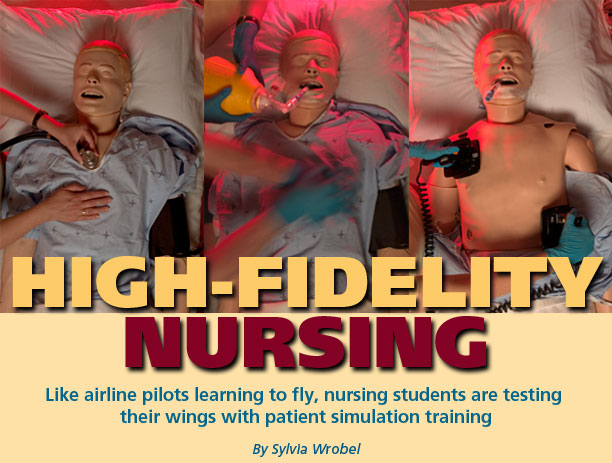

Noelle can deliver a baby every five

minutes if and when the nursing faculty need her to. But she is

only one of the life-size mannequins—officially known as high-fidelity

human patient simulators—helping revolutionize clinical education

in the Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing. Her older and even

more sophisticated brother, SimMan, has realistic heart and chest

sounds. His chest rises and falls with each breath, his pulses are

palpable, and he groans with pain, answers questions, and asks for

help. He—or she, with the quick addition of a wig, female

anatomy, and softer voice—is dependably unhealthy, suffering

whatever ailment and requiring whatever diagnosis and treatment

that undergraduate or graduate students need to learn.

When students meet SimMan shortly

after they enter nursing school, he usually has chest pain and difficulty

breathing. They painstakingly take his vital signs and history,

which he provides between wheezes, and study the monitor over his

head. By the time they are seniors, his problems have become more

critical—an undiagnosed pulmonary embolus, for example—and

so have the decisions they need to make. Wrong ones, or ones made

too slowly, and his respiration slows and eventually stops. “What

could we have done differently?” asks the supervising faculty

member. For the rest of their professional lives, faced with flesh-and-blood

patients with similar problems, the shocked students will remember

those answers.

For the rest of their professional lives, faced with flesh-and-blood

patients with similar problems, the shocked students will remember

those answers.

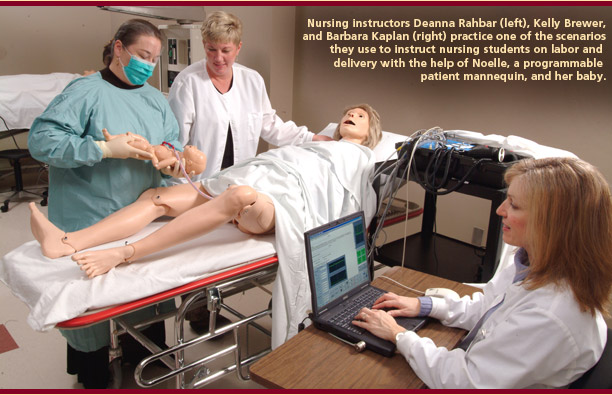

“These simulations become very

real to our students,” says Barbara Kaplan, coordinator of

the Charles F. and Peggy Evans Center for Caring Skills. No one

would mistake expressionless Noelle, her little baby with its protruding

umbilical cord, or SimMan with his injectable rubber arm patches,

for living, breathing humans. What quickens the students’

heartbeats, what makes them impulsively reach out to stroke the

mannequin’s arm in comfort, are the patient care scenarios

carefully planned and programmed by nursing faculty like Corrine

Abraham (for undergraduates), Julie Davey (for graduate students)

and Bethany Robertson (who developed the Noelle program) in collaboration

with Kaplan. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

From

Learning to Doing

imulation is the single most important trend in nursing education

today, the way to move from learning to doing,” says Darla

Ura, clinical associate professor of adult and elder health and

director of the Evans Center. Its use, she adds, is non-negotiable

in today’s health care environment. High patient acuity (seriousness

of disease on admittance) and compressed length of stay leave little

time for clinical education. A cholecystectomy patient who might

have spent a week or 10 days in the hospital when Ura entered practice

now has the operation on an outpatient basis or a 24-hour short

stay (most likely a laparoscopic procedure the surgeon first learned

using a virtual reality simulator). At the same time, nurses on

the medical-surgical unit or in the ICU are increasingly

imulation is the single most important trend in nursing education

today, the way to move from learning to doing,” says Darla

Ura, clinical associate professor of adult and elder health and

director of the Evans Center. Its use, she adds, is non-negotiable

in today’s health care environment. High patient acuity (seriousness

of disease on admittance) and compressed length of stay leave little

time for clinical education. A cholecystectomy patient who might

have spent a week or 10 days in the hospital when Ura entered practice

now has the operation on an outpatient basis or a 24-hour short

stay (most likely a laparoscopic procedure the surgeon first learned

using a virtual reality simulator). At the same time, nurses on

the medical-surgical unit or in the ICU are increasingly responsible for more tasks and sicker patients. Although senior

nursing students still have rotations through Emory and other area

hospitals, much of the hands-on learning most practicing nurses

acquired in clinical settings now must be taught in simulation laboratories.

responsible for more tasks and sicker patients. Although senior

nursing students still have rotations through Emory and other area

hospitals, much of the hands-on learning most practicing nurses

acquired in clinical settings now must be taught in simulation laboratories.

Changing the traditional “see

one, do one” method of teaching from human patients to simulated

ones gained further support after a hard-hitting Institute of Medicine

report focused on medical errors and how to reduce them (“To

Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System,” 1999).

Whatever the reasons behind it, this

shift to simulation suits the nursing students just fine. Because

the patients aren’t real, even students early in their training

are allowed to become more involved in hands-on care, critical decision-making,

and teamwork. Like airline pilots crashing and burning repeatedly

as they “fly” in simulated cockpits, nursing students

can make mistakes without causing disasters. No one gets hurt from

errors in simulation, and students learn lessons that will benefit

them and their patients for the rest of their careers.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

A

(simulated) hospital of its own

lmost overnight, the Evans Center enabled the nursing school to

become the Woodruff Health Sciences Center’s biggest user

of high-fidelity mannequins.

lmost overnight, the Evans Center enabled the nursing school to

become the Woodruff Health Sciences Center’s biggest user

of high-fidelity mannequins.

The use of such technology had not

been an option in the nursing school’s former building (located

on Asbury Circle behind Emory University Hospital), which wasn’t

wired adequately for students even to operate an electric hospital

bed and where the only life-size “care dolls” (less

realistic models used for changing dressings, setting casts, and other tasks) had no flexible joints, much less pulses and voices.

In the late 1990s, a grant from the Helene Fuld Health Trust made

possible the purchase of more realistic mannequins, ones with veins

in which an IV could be started, patches for injections (saving

hundreds of oranges used for practice each year), and programmable

heart and breath sounds. Ura and other faculty began visiting sister

nursing schools where simulation was already taking off and compiled

the school’s “must have” shopping list in hopes

that if they planned well, the money would come.

other tasks) had no flexible joints, much less pulses and voices.

In the late 1990s, a grant from the Helene Fuld Health Trust made

possible the purchase of more realistic mannequins, ones with veins

in which an IV could be started, patches for injections (saving

hundreds of oranges used for practice each year), and programmable

heart and breath sounds. Ura and other faculty began visiting sister

nursing schools where simulation was already taking off and compiled

the school’s “must have” shopping list in hopes

that if they planned well, the money would come.

Miraculously, it did. As the nursing

school prepared to move into its new building on Clifton Road in

December 2000, the school learned that the late Charles and Peggy

Evans, who built an automobile sales enterprise in the Atlanta area,

had bequeathed Emory a multimillion dollar gift in appreciation

for the medical and nursing care they received before their deaths.

What better way to honor their generosity and memory than to build

a center where such caring skills could be taught? (A large portion

of their gift also is being used by the medical school for a new

education building and programs.)

Already twice renovated to expand

size and technology, the Evans Center includes a small hospital

ward, with eight beds separated by privacy curtains. Until recently,

ever-pregnant Noelle stayed in another spacious room near the ward

with her newborn. Two SimMan mannequins kept her company, along

with other life-size children and adult mannequins, care dolls,

and numerous simulated body parts, such as the shoe box-size pelvis

on which students learn catheterization. Computers spit out realistic

laboratory results and X-rays.

In May, the first Emory BSN students

with two years of simulation training graduated, entering nursing

practice with unprecedented experience and greater confidence in

a wide range of clinical situations. This summer, the Evans Center

added an observation and control room (where Noelle and SimMan now

reside) with one-way mirrors, video cameras, and enhanced technology.

In September, an ongoing teaching partnership between nursing and

medicine was expanded as fourth-year medical students and nursing

seniors began working together in the Evans Center to learn how

to respond as a team in a medical emergency.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Playing

well with others

he

School of Nursing is well on its way to becoming a national leader

in simulation training, according to Dr. Carol Fowler Durham, a

simulation expert at the University of North Carolina School of

Nursing. When Durham came to Emory to give the 2004 he

School of Nursing is well on its way to becoming a national leader

in simulation training, according to Dr. Carol Fowler Durham, a

simulation expert at the University of North Carolina School of

Nursing. When Durham came to Emory to give the 2004 David Jowers Lecture and conduct a simulation workshop for nursing

faculty, she was impressed by the high-tech Evans Center and the

faculty’s enthusiasm and eagerness to use simulation. In many

ways, especially in terms of teamwork between the medical and nursing

schools, the school is “way ahead of the game,” she

says.

David Jowers Lecture and conduct a simulation workshop for nursing

faculty, she was impressed by the high-tech Evans Center and the

faculty’s enthusiasm and eagerness to use simulation. In many

ways, especially in terms of teamwork between the medical and nursing

schools, the school is “way ahead of the game,” she

says.

Last year, the School of Nursing and

the School of Medicine jointly recruited Dr. Martin Reznek, a highly

experienced expert in simulation training for medicine and nursing,

to expand simulation training opportunities for students in both

fields.

“Emergency medicine is a great

field for this kind of collaborative training,” says Reznek,

an assistant professor in the School of Medicine. “When a

patient arrives in the ER, there are always more tasks than one

person can do, forcing quick decisions and delegation of responsibilities.

Nurses and physicians interact in crisis situations all day long,

and the physician/nurse hierarchy is not as firmly established as

in some fields.”

Reznek’s tasks include expanding

simulation programs for nursing and medical students and bringing

in grants to the nursing school. The new class that began in September—“Learning

in Interdisciplinary Teams Makes Us Safer” (LITMUS)—does

both, having won an educational grant from the university.

In LITMUS, groups of two medical students

and two nursing students listen to lectures about the different

tasks that need to be done in specific medical crises and how physicians and nurses

work together to get those tasks done quickly and correctly.

be done in specific medical crises and how physicians and nurses

work together to get those tasks done quickly and correctly.

The simulation begins when a code

sounds, and the four students crowd around a bed where SimMan is

in programmed peril. As in the real ER, they don’t know what

to expect. The case may be a cardiac arrhythmia that has turned

into cardiac arrest. Or it may involve the altered mental status

of head trauma. “Part of the art form of developing simulations,”

says Reznek, “is to match what students know intellectually

and what they need to know operationally.”

Whatever the case, learning to respond

as a team is the primary imperative. That’s not easy to learn

in the simulation’s crisis atmosphere and with two different

professional cultures and four personalities around the bedside.

But it is a lot easier—and a lot safer, as the course title implies—than trying to learn it for the first time around

the bedside of a barely living patient. And it will give students

an early chance to discover the strengths of each other’s

profession.

implies—than trying to learn it for the first time around

the bedside of a barely living patient. And it will give students

an early chance to discover the strengths of each other’s

profession.

After the simulation ends, the faculty

undertake the most important step—debriefing. Students watch

their simulation on videotape made in the Evans Center’s new

control room and answer two questions that open each session: What

did you do well? What could you have done better?

More steps are in store for faculty,

says Reznek. Using the videotapes, they can hone the scenarios and

curriculum to improve team interaction and conduct research on the

effectiveness of simulation and its impact on patient safety. Other

research may focus on whether doctors and nurses have different

perceptions of what is important for patient care that may affect

how well they work as a team.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Simulation,

synthesis, and the making of a nurse

xuberant

students often claim they learned more in an hour in the simulation

laboratory than they learned all semester. Their instructors just

smile. They know the real strength of simulation is to show students

the effects of the pathophysiology they have been studying and to

synthesize theory into practice. They also know that moment of synthesis

is both an emotionally and intellectually powerful experience that

helps students become better nurses more quickly. xuberant

students often claim they learned more in an hour in the simulation

laboratory than they learned all semester. Their instructors just

smile. They know the real strength of simulation is to show students

the effects of the pathophysiology they have been studying and to

synthesize theory into practice. They also know that moment of synthesis

is both an emotionally and intellectually powerful experience that

helps students become better nurses more quickly.

Kaplan tells of a senior nursing student

who was crestfallen after her first simulation with a code, the

alarm that sounds when a patient turns critical. “I was awful,”

she said, near tears. “How will I ever learn enough?”

The next week, during her hospital

rotation, the patient with whom she was talking suddenly lost consciousness.

The student called the code, grabbed the crash cart, placed a board

under the patient in preparation for defibrillation/compression,

and began CPR. “I knew what to do,” she later told Kaplan

gleefully.

SimMan (and the nursing faculty) had

done it once again.

Sylvia

Wrobel is the former associate vice president for health sciences

communications and a frequent contributor to Emory’s health

sciences publications.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|