|

|

| |

A

maternal link to prostate cancer?

Retinal chips

Addressing disparities in cardiovascular

health

Safer teens behind the wheel

In search of a better transplant drug

Aging with less grace, spatially speaking

Junk DNA and social behavior

|

Finding

missing cases of HIV

Female sex hormone reduces stress response

Treating depression, deep within the brain

Easy on the heart and wallet

Applying nanotechnology to cardiovascular

disease

Eat mor veggees |

|

|

|

|

| |

A

maternal link to prostate cancer?

More

than 20 million men in the united states

with a particular set of inherited characteristics and mutations

in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) are at significantly increased risk

for developing renal and prostate cancers, according to research

at Emory. Mitochondrial DNA, which contains a small number of

genes inherited mainly from the mother, is found in the hundreds

of mitochondria located in the cytoplasm outside of each cell’s

nucleus.

Emory

urologist John Petros has found variations in

the mtDNA of men from the general population compared with men

with renal and prostate cancer. His study showed that only 9.6%

of the general population of Caucasian American participants had

mtDNA in haplogroup U. By contrast, 16.7% of prostate cancer patients

and 20.7% of renal cancer patients exhibited the haplogroup U

signature. A haplotype is a combination of variations in a gene. Emory

urologist John Petros has found variations in

the mtDNA of men from the general population compared with men

with renal and prostate cancer. His study showed that only 9.6%

of the general population of Caucasian American participants had

mtDNA in haplogroup U. By contrast, 16.7% of prostate cancer patients

and 20.7% of renal cancer patients exhibited the haplogroup U

signature. A haplotype is a combination of variations in a gene.

In addition to variations in haplogroup, Petros also found that

12% of prostate cancer patients had mutations in the COI gene,

an mtDNA cytochrome oxidase subunit, compared with less than 2%

of patients who were cancer-free.

In a second Emory study on prostate

cancer, led by Winship Cancer Institute’s Jin-Tang Dong,

researchers found that a gene named ATBF1 may contribute to the

development of prostate cancer through acquired mutations and/or

loss of expression. Although previous research has suggested that

a section of chromosome 16 harbors a tumor-suppressor gene in

several types of human cancers, the particular gene responsible

has not been identified previously.

By studying the genes within the

section of chromosome 16, the Emory team found that ATBF1 was

a strong candidate for an important tumor-suppressor gene because

its function is frequently lost in prostate cancer through gene

mutations and/or loss of expression. In addition, ATBF1 was found

to inhibit cell growth in culture dishes. A tumor-suppressor gene

is a gene whose loss of function contributes to the development

of cancer.

ATBF1 helps regulate the expression

of other genes. If its function is impaired by mutations or loss

of expression, a cell could lose the control of cancer genes.

The Myb oncogene, for example, is normally inhibited by ATBF1,

but it can be activated if ATBF1 is lost.

“Sporadic cancers often are

the result of multiple genetic alterations that accumulate over

time,” says Dong, “but only a small number of genes

have been shown to undergo these frequent mutations. Because ATBF1

inhibits cell proliferation, frequent acquired mutations that

inhibit the gene, such as the ones we found, could lead to a lack

of growth control in prostate cancer. Because gene deletion in

chromosome 16 is common in many types of cancer, including lung,

head and neck, nasopharynx, stomach, breast, and ovary, ATBF1

could be involved in the development of these cancers as well.”

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

| |

Retinal

chips

|

|

| |

In

an expanded clinical trial, Emory surgeons have implanted a tiny retina microchip, much

smaller than a penny, in several patients with retinitis

pigmentosa to determine if it will improve functional or

slow progression of vision loss. Five patients with moderate-to-severe

vision loss participated in the experimental treatment,

developed by Optobionics Corp. Researchers hope the retinal

chips will improve the quality of life for patients with

this debilitating disease.

Emory surgeons have implanted a tiny retina microchip, much

smaller than a penny, in several patients with retinitis

pigmentosa to determine if it will improve functional or

slow progression of vision loss. Five patients with moderate-to-severe

vision loss participated in the experimental treatment,

developed by Optobionics Corp. Researchers hope the retinal

chips will improve the quality of life for patients with

this debilitating disease. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

| |

Addressing

disparities in cardiovascular health

|

|

| |

The

NIH has awarded Emory and Morehouse School of Medicine $6

million for a five-year partnership to address health disparities

between African Americans and Caucasians at high risk for

cardiovascular disease. The program is one of six nationwide

funded by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. The

NIH has awarded Emory and Morehouse School of Medicine $6

million for a five-year partnership to address health disparities

between African Americans and Caucasians at high risk for

cardiovascular disease. The program is one of six nationwide

funded by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.

Known as META-Health (Morehouse

and Emory are Teaming up to eliminAte Health Disparities),

the Atlanta program will focus on metabolic syndrome, a

cluster of health risk factors that includes hypertension,

abnormal cholesterol, high triglycerides, abdominal obesity,

and elevated blood glucose. People with three of these factors

are identified as having metabolic syndrome, indicating

a high risk for diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

The first goal of the study

is to identify differences in risk factors in African Americans

and Caucasians. The research team then will develop and

test targeted interventions aimed at improving overall cardiovascular

health.

Earlier studies indicate that

African Americans and Caucasians experience metabolic syndrome

differently, according to cardiologist Arshed Quyyumi, who

is leading Emory’s team. African Americans appear

to have lower incidence of cholesterol and triglyceride

abnormalities with a similar frequency of insulin resistance,

factors that contribute to underdiagnosis of the condition.

In addition, evidence suggests

that children of patients with the syndrome are at increased

risk of developing obesity and insulin resistance. META-Health

researchers hope to establish a genomic database to identify

genetic differences that would account for some of these

complications and disparities. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Safer

teens behind the wheel

Georgia’s

strong teen driving laws are working. In 1997, the Teenage and

Adult Driver Responsibility Act went into effect, ushering in

incentives to deter excessive speeding, consumption of alcohol

while driving, and other dangerous driving behaviors. It also

introduced graduated licensing, with provisions to restrict late- night

driving and the number of passengers in a teen’s vehicle.

Emory researchers—led by Emergency Medicine Chair Arthur

Kellermann—recently completed a study to evaluate the law’s

long-term impact. They found that the rate of fatal crashes among

16-year-olds was 36.8% less than in the previous 5-1/2 years for

the same age group. Fatal crashes involving 17-year-olds also

were reduced. In comparing the driving results of 21-year-olds

in 1997 with those who turned 21 after the law’s enactment,

researchers found a 38% lower fatal crash rate for the group who

learned to drive under the new rules. night

driving and the number of passengers in a teen’s vehicle.

Emory researchers—led by Emergency Medicine Chair Arthur

Kellermann—recently completed a study to evaluate the law’s

long-term impact. They found that the rate of fatal crashes among

16-year-olds was 36.8% less than in the previous 5-1/2 years for

the same age group. Fatal crashes involving 17-year-olds also

were reduced. In comparing the driving results of 21-year-olds

in 1997 with those who turned 21 after the law’s enactment,

researchers found a 38% lower fatal crash rate for the group who

learned to drive under the new rules. |

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

| |

In

search of a better transplant drug

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

For

the past 20 years, doctors have treated transplant patients

with cyclosporine to suppress the immune system and prevent

organ rejection. However, the medication shuts down the

immune system, increases the risk of heart attacks, and

can damage the kidneys.

An investigational medication,

known as LEA29Y (belatacept), is proving effective in preserving

transplanted kidney function while avoiding those toxic

side effects. The preclinical research conducted with nonhuman

primates at the Yerkes National Primate Research Center

has led to human clinical trials to develop an effective

alternative to current therapies.

Chris Larsen (above) and Thomas

Pearson of the Emory Transplant Center with colleagues at

Bristol-Myers Squibb developed LEA29Y to selectively block

the second of two cellular signals—the co-stimulatory

signal—that the body needs to trigger an immune response.

Blocking this signal prevents organ rejection while allowing

the body to continue fighting other infections. Cyclosporine,

by contrast, indiscriminately targets and blocks other cellular

signal pathways.

Following in vitro studies,

during which the researchers observed LEA29Y was 10 times

more effective than cyclosporine in blocking the co-stimulatory

immune signal, Larsen and Pearson tested the drug in nonhuman

primates and found it significantly prolonged survival of

transplanted kidneys.

The research team recently

completed a phase 2 clinical study comparing LEA29Y with

cyclosporine in human kidney transplant patients. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Aging

with less grace, spatially speaking

When

it comes to aging, women may have another advantage over men.

Research conducted at Yerkes National Primate Research Center

shows that male nonhuman primates are more susceptible to age-related

cognitive decline than females.

In the study, neuroscientists Agnes

Lacreuse and James Herndon observed young and elderly nonhuman

primates performing tasks that measured spatial memory, which

records environmental and spatial-orientation information. The

researchers presented  each

animal with an increasing number of identical disks, and the animals

had to identify each disk as it appeared in a new location. each

animal with an increasing number of identical disks, and the animals

had to identify each disk as it appeared in a new location.

The young adult males outperformed

the females, a finding consistent with human data that shows men

have a higher capacity than women for maintaining or updating

spatial information. Among older nonhuman primates, the researchers

found cognitive decline in both sexes. However, sex differences

in the spatial memory performance tasks had disappeared. The finding

suggests that spatial abilities declined at a greater rate in

males than in females as they got older.

On the human front, an NIH clinical

trial that included Emory researchers examined the ability of

drugs to prevent or delay the onset of Alzheimer’s disease.

Patients with mild cognitive impairment who were treated with

Aricept had a lower rate of progression to symptoms of Alzheimer’s

during the early part of treatment. Vitamin E, however, was found

to have no benefit in delaying the disease. |

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

| |

Junk

DNA and social behavior

|

|

| |

Why

are some people shy while others are outgoing?

A recent study in Science demonstrates for the first time

that social behavior may be shaped by differences in the

length of seemingly nonfunctional DNA, sometimes referred

to as junk DNA. The finding by researchers at Yerkes National

Primate Research Center and the Center for Behavioral Neuroscience

has implications for understanding human social behavior

and disorders, such as autism.

The study examined whether

the junk DNA, formally known as microsatellite DNA, associated

with the vasopressin receptor gene affects social behavior

in male prairie voles, a rodent species. Researchers bred

two groups of prairie voles with short and long versions

of the junk DNA. By comparing the behavior of male offspring

after they matured, they discovered microsatellite length

affects gene expression patterns in the brain.

In the prairie voles, males

with long microsatellites had higher levels of vasopressin

receptors in brain areas involved in social behavior and

parental care, particularly the olfactory bulb and lateral

septum. These males spent more time investigating social

odors and approached strangers more quickly. They also were

more likely to form bonds with mates, and they spent more

time nurturing their offspring. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Finding

missed cases of HIV

Although

standard tests that measure antibody response to HIV have become

increasingly sensitive, cases are still missed. In a recent study,

researchers at Emory, the University of North Carolina at Chapel

Hill, and the Georgia Department of Human Resources used nucleic

acid amplification testing (NAAT) in addition to standard tests

to screen clients at urban clinics and HIV testing sites in Atlanta.

The combined approach, they found, uncovered 6% more cases of

HIV infection than current standard practice. Although

standard tests that measure antibody response to HIV have become

increasingly sensitive, cases are still missed. In a recent study,

researchers at Emory, the University of North Carolina at Chapel

Hill, and the Georgia Department of Human Resources used nucleic

acid amplification testing (NAAT) in addition to standard tests

to screen clients at urban clinics and HIV testing sites in Atlanta.

The combined approach, they found, uncovered 6% more cases of

HIV infection than current standard practice.

NAAT-based screening can identify

people with acute HIV infection earlier when they may be most

infectious and at risk for spreading the virus, according to Emory

infectious disease specialist Frances Priddy (above), who recently

presented the findings at the 12th Conference on Retroviruses

and Opportunistic Infections. |

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

| |

Female

sex hormone reduces stress response

|

|

| |

A

steroid hormone released during the metabolism of progesterone

reduces the brain’s response to stress in rats, according

to research by scientists at Emory School of Medicine, Yerkes

National Primate Research Center, and the Center for Behavioral

Neuroscience. The researchers found that allopregnanolone,

a progesterone metabolite, reduces the brain’s response to corticotropin-releasing factor

(CRF), a hormone that plays an important role in the stress

response.

the brain’s response to corticotropin-releasing factor

(CRF), a hormone that plays an important role in the stress

response.

In a test to gauge stress

and anxiety, the researchers compared how female rats with

different levels of estrogen and progesterone reacted to

loud noises after injections of CRF. These injections usually

increase the acoustic startle response. In comparing the

acoustic startle responses after CRF injection in three

groups—estrogen-only, estrogen-plus-progesterone,

and a control group—the researchers found that the

startle response was unaffected in both the estrogen-only

and control groups. However, in the estrogen-plus-progesterone

group, CRF-enhanced startle was significantly lower.

The experiment and others

led the scientists to conclude that progesterone inhibits

the effect of CRF on the acoustic startle response. This

finding correlates with clinical evidence that some people

suffering from depression and anxiety have low allopregnanolone

levels that normalize after treatment with anti-depressant

medications. The research, published in the Journal of Neuroscience,

could lead to drug development and new approaches for controlling

mood disorders in women. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Treating

depression, deep within the brain

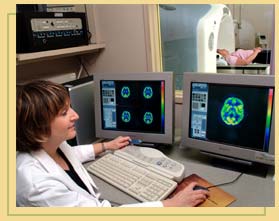

Deep

brain stimulation may have clinical benefits for people

with severe depression who have failed other treatments, according

to a study published in the March issue of Neuron. In

previous studies at the University of Toronto, where she began

the research, Helen Mayberg, now a professor in the Departments

of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and Neurology at Emory,

found that the subgenual cingulate region of the brain (Cg25)

plays a critical role in modulating sadness and negative mood

states in both healthy and depressed people. She wondered if stimulation

of this region could improve the treatment of depression, as with

other neurologic disorders such as Parkinson’s disease,

epilepsy, and dystonia. Deep

brain stimulation may have clinical benefits for people

with severe depression who have failed other treatments, according

to a study published in the March issue of Neuron. In

previous studies at the University of Toronto, where she began

the research, Helen Mayberg, now a professor in the Departments

of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and Neurology at Emory,

found that the subgenual cingulate region of the brain (Cg25)

plays a critical role in modulating sadness and negative mood

states in both healthy and depressed people. She wondered if stimulation

of this region could improve the treatment of depression, as with

other neurologic disorders such as Parkinson’s disease,

epilepsy, and dystonia.

Guided by MRI, Mayberg’s team

implanted thin wire electrodes in the brain region of Cg25 in

six patients. The wires were connected under the skin of the neck

to a pacemaker-like device that directed the electric current.

During the six-month study, four

of the six patients showed a significant response with sustained

improvement. PET scans also showed a significant response in the

frontal cortex, hypothalamus, and brainstem, consistent with findings

seen with successful response to medication or psychotherapy in

less severely ill patients.

This

study was the culmination of 15 years of research using brain

imaging technology, says Helen Mayberg (shown above). |

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

| |

Easy

on the heart and the wallet

|

|

| |

The

drug eplerenone, which blocks aldosterone—a hormone involved in regulating

blood levels of sodium and potassium as well as the constriction

of blood vessels—not only helps people with heart

disease live longer, it also is cost-effective, according

to an international study, led by the Emory Heart Center’s

William Weintraub. Researchers found a significant decrease

in mortality in patients with left ventricular systolic

dysfunction and congestive heart failure following heart

attack. Also, the drug added only about $3.60 (wholesale),

on average, to treatment costs. In further analysis, researchers

calculated the cost for each quality-life-year gained by

patients treated with eplerenone at $13,178. “Health

economists generally regard any price below $50,000 a year

as cost-effective,” Weintraub says.

blocks aldosterone—a hormone involved in regulating

blood levels of sodium and potassium as well as the constriction

of blood vessels—not only helps people with heart

disease live longer, it also is cost-effective, according

to an international study, led by the Emory Heart Center’s

William Weintraub. Researchers found a significant decrease

in mortality in patients with left ventricular systolic

dysfunction and congestive heart failure following heart

attack. Also, the drug added only about $3.60 (wholesale),

on average, to treatment costs. In further analysis, researchers

calculated the cost for each quality-life-year gained by

patients treated with eplerenone at $13,178. “Health

economists generally regard any price below $50,000 a year

as cost-effective,” Weintraub says. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Applying

nanotechnology to cardiovascular disease

The

National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) of the NIH has

awarded researchers from Georgia Institute of Technology and Emory

$11.5 million to establish a new research program focused on creating

advanced nanotechnologies to analyze plaque formation on the molecular

level and detect plaque at its early stages.

The multidisciplinary program, part

of NHLBI’s Program of Excellence in Nanotechnology (PEN),

is headed by Gang Bao, a professor in the Wallace H. Coulter Department

of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech and Emory. The program,

one of four  national

PEN awards, includes 12 faculty from both institutions and is

based at Emory. It will focus primarily on detecting plaque and

pinpointing its genetic causes with three types of nanostructured

probes—molecular beacons, semiconductor quantum dots, and

magnetic nanoparticles. national

PEN awards, includes 12 faculty from both institutions and is

based at Emory. It will focus primarily on detecting plaque and

pinpointing its genetic causes with three types of nanostructured

probes—molecular beacons, semiconductor quantum dots, and

magnetic nanoparticles.

A molecular beacon is a biosensor

about 4 to 5 nanometers in size that can seek out and detect specific

target genes. It is a short piece of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA)

in the shape of a hairpin loop with a fluorescent dye molecule

at one end and a “quencher” molecule at the other

end. The ssDNA is synthesized to match a region on a specific

messenger RNA (mRNA) that is unique to the gene. The fluorescence

of the beacon is quenched, or suppressed, until it seeks out and

binds to a complementary target mRNA, which causes the hairpin

to open up and the beacon to emit light.

The level of gene expression within

a cell can reflect susceptibility to disease. The fluorescence

from the beacons will vary with the level of the target genes’

expression in each cell, creating a glowing marker if the cell

has a detectable level of gene expression that is known to contribute

to cardiovascular disease.

To complement these studies, the

team will develop quantum dot nanocrystal probes and use them

to study protein molecular signatures of cardiovascular disease.

Quantum dots are nanometer-sized semiconductor particles that

have unique electronic and optical properties due to their size

and highly compact structure. Quantum dot-based probes can act

as markers for specific proteins and cells and can be used to

study protein-protein interactions in live cells or to detect

diseased cells.

Other research will use magnetic

nanoparticles to detect early-stage plaques. These particles will

target specific proteins on the surface of cells in a plaque and

serve as a contrast agent in MRI, providing an image of plaque

formation. |

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

| |

Eat

mor veggees

|

|

| |

If

the next 100 billion burgers sold under the Golden Arches

were veggie-based rather than beef, Americans’ cholesterol

levels, fiber intake, and overall health would improve,

according to an article in the May issue of the American

Journal of Preventive Medicine. Lead author Erica Frank

of Emory’s Department of Family and Preventive Medicine

compared the McVeggie burger (sold in Canada and some major

cities across the United States) to the beef burger, finding

that the switch to the plant-based choice would result in

1 billion more pounds of fiber, 550 million fewer pounds

of saturated fat, 1.2 billion fewer total pounds of fat,

and 660 million more pounds of protein. Supersize that,

and you’ve got a healthier country. If

the next 100 billion burgers sold under the Golden Arches

were veggie-based rather than beef, Americans’ cholesterol

levels, fiber intake, and overall health would improve,

according to an article in the May issue of the American

Journal of Preventive Medicine. Lead author Erica Frank

of Emory’s Department of Family and Preventive Medicine

compared the McVeggie burger (sold in Canada and some major

cities across the United States) to the beef burger, finding

that the switch to the plant-based choice would result in

1 billion more pounds of fiber, 550 million fewer pounds

of saturated fat, 1.2 billion fewer total pounds of fat,

and 660 million more pounds of protein. Supersize that,

and you’ve got a healthier country. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|